Dr Thomas Akehurst teaches history and politics at the University of Sussex and the Open University. He is the author of The Cultural Politics of Analytic Philosophy: Britishness and the Spectre of Europe.

Dr Thomas Akehurst teaches history and politics at the University of Sussex and the Open University. He is the author of The Cultural Politics of Analytic Philosophy: Britishness and the Spectre of Europe.

In this blog post, he makes the case for the value of approaching philosophy through cultural history.

One of the problems facing academic philosophy in the 20th century was that it became, well, more and more academic – specialised, cut off from the interests of the rest of humanity, and it seems not able, or not willing to address our concerns.

This disconnect between academic philosophy and human life, called the “existential gap” has been seen as a particular feature of analytic philosophy – the dominant tradition in British and American universities.[1] Philosophers’ attitudes to this gap have varied tremendously. In the 1950s, many of those practising the discipline in its then powerhouse, Oxford, seemed to revel in its abstruse irrelevance. The philosopher G. J. Warnock reflects back on the period:

I did not believe that it was likely to contribute to the solution of the problems of the post war world; I did not believe it would contribute, certainly or necessarily, to the solution of any philosophical problem. But it was enormously enjoyable; it was not easy, it exercised the wits; and those who think it can never be valuably instructive have simply never tried, or perhaps are no good at it.[2]

And perhaps many academic philosophers and aspiring academic philosophers continue to share something like this view. It’s enjoyable, it pays the bills. There are excellent opportunities to travel. However the 21st century has also seen the revival of attempts to reconnect analytic philosophy with the rest of us. Popular philosophy, applied philosophy, now practical philosophy and philosophy therapy have all become swelling areas of output. Texts in these genres now dominate the two shelves reserved for philosophy books in some larger branches of Waterstones. This desire to speak to a wider audience can only be a good thing if we believe that life, on balance, is worth thinking about.

Unfortunately, this desire for outward-looking communication on the part of philosophers, hasn’t yet been equalled by the willingness for inward looking disciplinary self-scrutiny. Philosophy arises from its culture and context. It carries the assumptions of its time and place and of its historical development. Sometimes this baggage is in plain sight, more commonly it’s hidden from philosopher and reader alike: contraband at the bottom of a suitcase the philosophers didn’t pack themselves.

Contemporary British analytic philosophy has shown very little interest in examining the cultural and political ideas and attitudes it has been moulded and formed by over the years. And this is why the cultural history of philosophy is such an important field. The history of philosophy is shaped by many factors. Philosophical arguments, for sure, have an impact on the direction of the discipline. But a much broader range of issues also help shape and form apparently abstract philosophical positions and developments. And it’s here that cultural-political histories, as well as institutional histories, become very important if we want to understand the philosophical thought that’s presented for our edification.

Cultural history of philosophy is not (yet) the thriving cottage industry it might be. Yet some work has been done. John McCumber has explored how McCarthyism in the US put powerful external pressure on philosophers to abandon certain fields of study, or tailor their conclusions in a safe political direction. Those who did not could expect stymied or terminated careers. George Reisch explores a similar dynamic in the philosophy of science. [3]

My own work points to the way that British philosophers drew conclusions about the wars against Germany in the first half of the twentieth century – and how these conclusions fed through into their philosophical work.[4] They identified a tradition of German philosophy they believed resulted in German aggression, and ultimately in National Socialism. These attitudes and assumptions on the part of the British were poorly defended in their written work, but nevertheless contributed to a purging of the canon of philosophy after 1945. A swathe of European philosophy from Hegel onwards was subject to dismissal and mockery followed by an “active process of forgetting and exclusion”.[5] This exclusionary process marks a crucial moment in the creation of the rift between analytic and continental philosophy that continues to dominate European and American thought.[6]

My own work points to the way that British philosophers drew conclusions about the wars against Germany in the first half of the twentieth century – and how these conclusions fed through into their philosophical work.[4] They identified a tradition of German philosophy they believed resulted in German aggression, and ultimately in National Socialism. These attitudes and assumptions on the part of the British were poorly defended in their written work, but nevertheless contributed to a purging of the canon of philosophy after 1945. A swathe of European philosophy from Hegel onwards was subject to dismissal and mockery followed by an “active process of forgetting and exclusion”.[5] This exclusionary process marks a crucial moment in the creation of the rift between analytic and continental philosophy that continues to dominate European and American thought.[6]

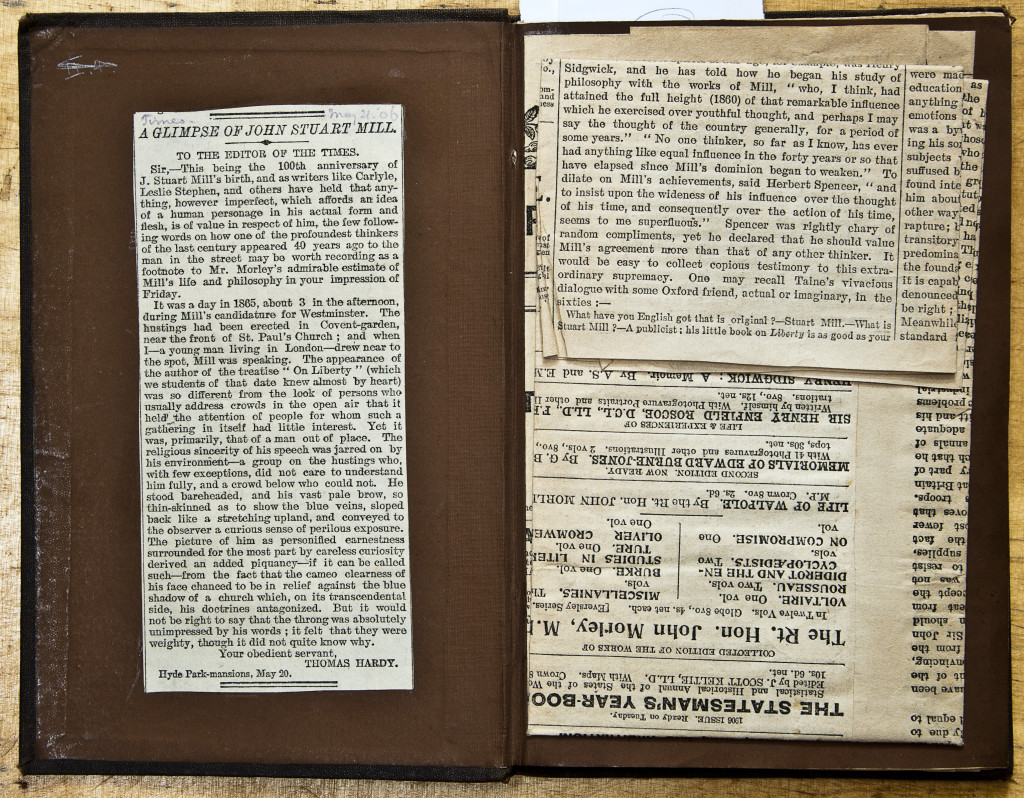

In the mid-century, British philosophers emphasised the warts of the German/European tradition – Nietzsche was a megalomaniac, Hegel a deceptive state-serving nationalist, Rousseau a sort of evil seductive genius.[7] Even as they condemned German (and allied) thought for its fascist tendencies, the British philosophers held up their own tradition as one of congenital liberality – pointing to a virtuous canon of British thinkers going back to John Locke. These British philosophers were portrayed as liberal in politics, rigorous in philosophy and noble in character. They were carefully airbrushed to remove the stains of historical indiscretion: such as the sanction Locke gave to the expropriation of native American lands, or John Stuart Mill’s paternalist racism, much less the anti-Semitism of Bertrand Russell, the 20th-century hero of British analytic philosophy.[8]

Once philosophy is allied to a national cause, you get nationalist philosophies, with the virtues of “our boys” relentlessly juxtaposed to the vices of the enemy. The German philosophers of the 19th century were no more Nazis than the British philosophers of previous ages were saints. But philosophy mobilized for war resembles the nation-state mobilized for war. Nationalist philosophy is distorting, and homogenizing.

That, at times of existential threat, philosophers respond like many other people and get defensive and jingoistic is perhaps not very surprising and not especially condemnable. And there’s no doubt that for the philosophers I’ve studied, Bertrand Russell, A.J. Ayer, Isaiah Berlin, R.M. Hare, amongst others, the Second World War was such a threat. Perhaps the realization that philosophers were ready to draw simple nationalist distinctions and assassinate the characters of fellow philosophers might give us reason to doubt some of the more grandiose claims about philosophy’s ability to cultivate calm rationality in its practitioners. But the Nazis were a terrifying threat – and there but for the grace of God go we all.

The problem is not that these men drew hasty conclusions. The trouble is that analytic philosophy has so solidly refused to countenance the possibility of any influence beyond the narrow scope of “strictly philosophical” questions that these hasty judgements and nationalist prejudices have been left unexplored and unchallenged by contemporary analytic philosophy. Not only have these attitudes gone underground and helped to to cement the foundations of the an unhelpful rift between analytic and continental philosophy, but at times they resurface in all their mid-century glory – in the analytic philosophers’ last words on Jacques Derrida, for example.[9]

Many analytic philosophers now want to be heard. But still very few seem to want to make a serious exploration of their past and its baggage. All the time this is the case, the discipline and what it offers to the public remain weighed down by unchecked cultural assumptions, political assumptions, and uncodified traditions. This short article has explored just some of these. Much remains to be explored. Analytic philosophy needs the cultural history of philosophy to sort through this historical accretion, assess it, and hopefully discard what is no longer needed. As a result, analytic philosophy may walk a little lighter and may find itself with new and surprising things to say to the public it wishes to cultivate.

References

[1] Preston, Aaron Analytic Philosophy: The History of an Illusion (Continuum, 2007) 25

[2] Warnock, G.J. Essays on J.L. Austin (Clarendon Press, 1973) 59.

[3] McCumber, John Time in the Ditch: American Philosophy and the Mccarthy Era (Northwestern University Press, 2001). Reisch, George A. How the Cold War Transformed Philosophy of Science: To the Icy Slopes of Logic. (CUP, 2005).

[4] Akehurst, Thomas L. The Cultural Politics of Analytic Philosophy: Britishness and the Spectre of Europe (Continuum 2010)

[5] West, David “The Contribution of Continental Philosophy,” in A Companion to Contemporary Political Philosophy, ed. Robert E. Goodin and Philip Pettit, Blackwell Companions to Contemporary Political Philosophy (Blackwell, 1995), 39.

[6] Simons, Peter. “Whose Fault? The Origins and Evitability of the Analytic Continental Rift”. International Journal of Philosophical Studies 9, no. 3 (August 2001).

[7] Berlin, Isaiah Freedom and Its Betrayal: Six Enemies of Human Liberty. Edited by H. Hardy. (Chatto and Windus, 2002). 43. Russell, Bertrand History of Western Philosophy (George Allen and Unwin, 1946). 794.

[8] Bracken, Harry “Essence, Accident and Race,” Hermathena, no. 116 (1973). Mill, John Stuart On Liberty, 1859, Moorhead, Caroline Bertrand Russell: a Life (1993 Sinclair-Stevenson Ltd.).

[9] Blackburn, Simon “Derrida May Deserve Some Credit for Trying, but Less for Succeeding,” The Times Higher Education Supplement, no. 1666 (12 November 2004).