Dr Demelza Hookway is an Honorary University Fellow in the College of Humanities at the University of Exeter and is currently writing a book on the cultural history of John Stuart Mill, based on her PhD research at Exeter. In this guest post for the Cultural History of Philosophy Blog, published to coincide with the UK General Election in 2015, she looks back to John Stuart Mill’s career as an MP and detects parallels with recent responses to Ed Miliband…

Dr Demelza Hookway is an Honorary University Fellow in the College of Humanities at the University of Exeter and is currently writing a book on the cultural history of John Stuart Mill, based on her PhD research at Exeter. In this guest post for the Cultural History of Philosophy Blog, published to coincide with the UK General Election in 2015, she looks back to John Stuart Mill’s career as an MP and detects parallels with recent responses to Ed Miliband…

As the UK’s parliamentary candidates have been scrutinised ahead of the 2015 General Election, journalistic attention has inevitably shifted from policy to character. Jeremy Paxman’s questioning of Ed Miliband during the ‘Battle for Number 10’ TV debate stands out as a memorable example of this character-focused approach. Towards the end of the interview, Paxman suggests that Miliband is too sensitive to be an effective leader (‘you know what people say about you because it’s hurtful, but you can’t be immune to it’, followed after the interview ended by an audible ‘are you OK, Ed?’), not manly enough to interact with other world leaders (a one-to-one encounter with Putin would leave Miliband ‘all over the floor in pieces’) and too intellectual to be popular with the electorate (‘they see you as a North London geek’). Miliband famously retorted with an assertion of his masculinity and resilience – ‘Hell yes, I’m tough enough’ – and you can watch the key section of the interview here.

The striking thing about Paxman’s accusations is how they evoke nineteenth-century debates about the qualities required to succeed in politics. The charges of sensitivity, effeminacy and intellectualism particularly recall the response to the renowned philosopher John Stuart Mill’s brief political career in the 1860s.

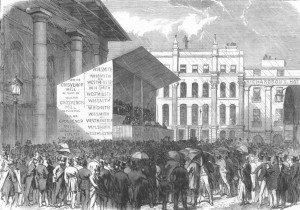

When Mill stood for Parliament in 1865 his liberal credentials were not in question. He was elected as MP for Westminster, and though he failed to win the seat again in 1868, he was often seen as originating, defining or exemplifying liberal principles. But doubts that the philosopher was tough enough for political life were expressed from the outset of his candidature. Like his political integrity, Mill’s intellectual stature was undeniable, but being a man of ideas was seen as a dubious qualification for a politician. As a result, his voice, his body and his emotions were all anatomised and often seen as lacking the strength expected of a man in such a prominent position. As a famous caricature of Mill in Vanity Fair in 1873 expressed it, this was ‘A Feminine Philosopher’.

Cartoon by ‘Spy’ (Leslie Ward) from Vanity Fair, London, 1873 (Photo by Universal History Archive/Getty Images)

The perception that Mill was moving from the safe seclusion of the study to the dangerous exposure of the platform generated much commentary. Supporters worried about how successfully he would be able to convey his theoretical knowledge in person, while detractors claimed that he was doomed in any attempt to do so. In an 1865 article on ‘Philosophers and Politicians’ The Saturday Review stated that ‘the prime characteristic of the Englishman is activity and energy, and the conflicts of the political arena gratify a national instinct’. [1] This model of political manliness was one against which Mill was constantly judged. As he set out to challenge ideas about essential differences between the sexes and to extend the suffrage to women, many commentators questioned Mill’s own performance of masculinity in the combative environment of Parliament.

In 2014, the Speaker of the House of Commons, John Bercow, commented on the problems politicians could face in making themselves heard over the noise in Parliament. This was clearly an issue for nineteenth-century parliamentarians, too, because a recurring subject of discussion was the suitability of Mill’s voice for public speaking. Those sympathetic to Mill worried that he had a weak voice and that this was compounded by a lack of oratorical skill. On first meeting Mill, Kate Amberley interpreted the quietness of his voice as evidence of his humility and likeability, recording in her journal, ‘he speaks in a very gentle voice, and is not in appearance like a great man’. Transposed to the House of Commons, however, the quietness took on a new, more disappointing aspect: ‘Mill’s speaking seems to bore the house, they say he has spoken too often – [too] much, and cannot be heard’. [2] The doorkeeper of the House of Commons, William White, thought that Mill ‘has not a powerful voice, but then it is highly pitched and very clear; and this class of voice goes much further than one of lower tone – as the ear-piercing fife is heard at a greater distance than the blatant trombone’. [3] For White at least, Mill’s quiet voice was a virtue rather than a cause for regret: a symbol of the different quality Mill introduced to parliamentary debate, and his far-reaching influence.

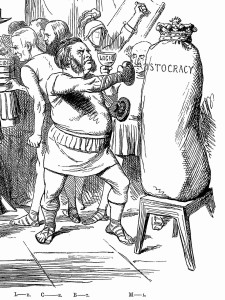

Another target for attention was Mill’s thin frame. Though broadly supportive of Mill’s parliamentary career, Britain’s foremost comic journal Punch consistently portrayed Mill as lacking the same robustly male physique as the central figures in the ‘battlefield’ of public life. [4]

Another target for attention was Mill’s thin frame. Though broadly supportive of Mill’s parliamentary career, Britain’s foremost comic journal Punch consistently portrayed Mill as lacking the same robustly male physique as the central figures in the ‘battlefield’ of public life. [4]

In February 1867, Punch ran a John Tenniel cartoon entitled ‘Gladiators Preparing for the Arena’, in which a diminutive Mill is positioned close to a bulky John Bright. The physical contrast is underscored by Bright squaring up to a punch bag marked ‘Aristocracy’ while a feeble-looking Mill with downcast eyes lurks behind him clutching a cup marked ‘Logic’. The following month Punch reported on Mill’s inaugural lecture as rector of St Andrews University, noting that he had ‘fought a good fight about education’, but depicting him as a tiny figure,in the guise of a naughty schoolboy, squaring up to a giant, rotund, cane-wielding don.

In Judy, a conservative journal set up to rival Punch, Mill’s feminisation was the most blatant: in their cartoons, he frequently appeared dressed as a woman. The striking cartoon accompanying ‘Parliamentary’ in Judy on 24 July 1867 shows Mill wearing a bonnet, holding a parasol, and daintily lifting his skirts out of the mud. Here, the focus is on Mill’s support for women’s suffrage. The article concentrates on the way ‘the Lady’s Mill’ had disappointed women by failing to secure them the vote. When Mill failed to retain his seat in Parliament, Judy made enthusiastic use of their established mode of representing him in ‘Miss Mill Joins the Ladies’ on 25 November 1868. ‘Philosophy’ is written on the lampshade in the hallway and is clearly aligned with Mill’s retreat into the private sphere.

By the time the caricature of Mill as ‘A Feminine Philosopher; appeared in Vanity Fair’s ‘Men of the Day’ series in March 1873, Mill was already strongly associated with ideas of femininity. The accompanying text explained that he was ‘a man of vast intellect and tender feelings’. Leslie Ward described making the study for the Vanity Fair caricature as he listened to Mill give a lecture on women’s rights at Exeter Hall. He remembers that as Mill ‘recited passages from his notes in a weak voice, it was made extremely clear that his pen was mightier than his personal magnetism upon a platform’. [5]

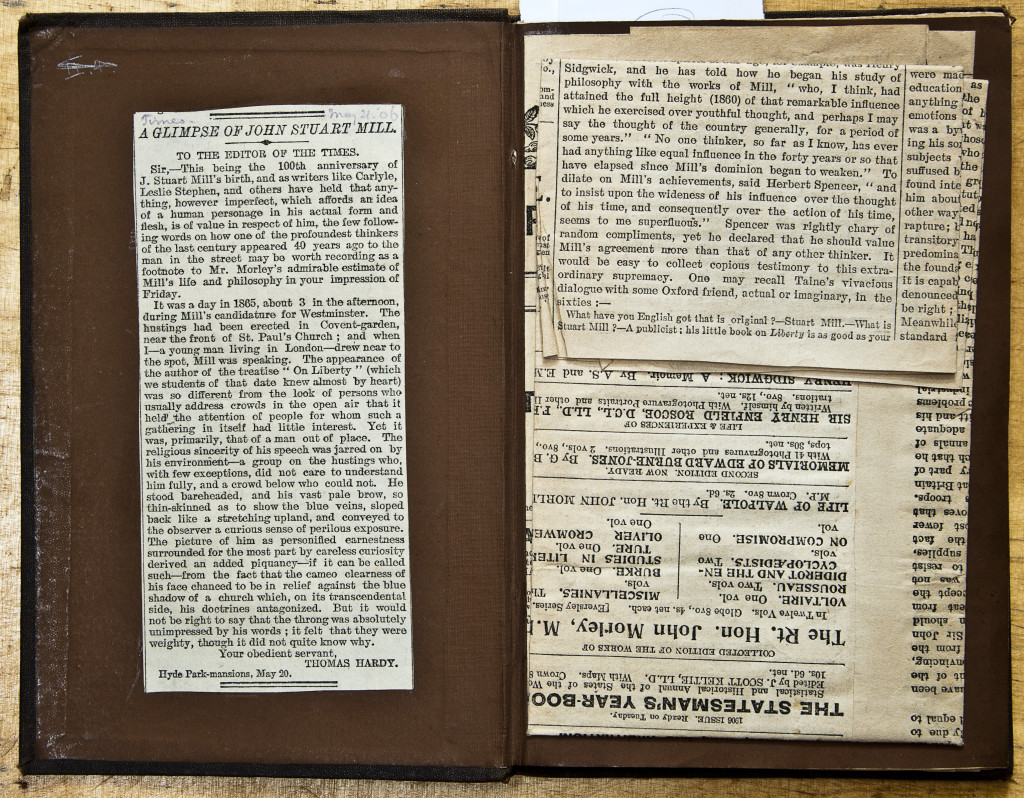

These ideas about Mill were in circulation before his entry into politics, but intensified during this time. They also persisted long afterwards. In a letter written to The Times and published on 20th May 1906 – 33 years after Mill’s death, but marking the one hundredth anniversary of his birth – Thomas Hardy recounted the moment in 1865 when he witnessed something quite remarkable: the philosopher making a public appearance as a parliamentary candidate, addressing the crowds gathered at the hustings in Covent Garden. Hardy’s letter renders in beautifully compact form many of the debates which took place in the second half of the nineteenth century about Mill’s status as a philosopher, a politician, and an advocate of women’s rights. Hardy’s copy of Mill’s On Liberty, which is in the archive at Dorset County Museum, has the letter, ‘A Glimpse of John Stuart Mill’, pasted inside the front cover. On the right hand side, folded up, is an article which appeared in the Times Literary Supplement a couple of days earlier. It was written by the Liberal politician, writer and editor John Morley, and paid tribute, in the most glowing terms, to Mill’s philosophical achievements. Hardy’s letter, as well as recounting a personal memory about Mill, was a response to the way in which John Morley had chosen to depict Mill, in grand and reverential terms, in this centenary piece. [6]

Morley was a friend and a follower of John Stuart Mill and unsurprisingly strikes a reverential tone in his piece for the Times Literary Supplement. Morley did allude to difficulties – the time before Mill achieved renown, the hostile reaction provoked by some of his opinions, and the uncertainty with which he was viewed by some of his fellow parliamentarians when he became an MP – but in his retrospective overview he also conveyed a sense of inevitability about Mill’s central role in the struggle for social change. In his record of Mill for posterity, Morley sought to affirm Mill’s manliness by asserting that he was a protagonist in the battleground of public opinion. In calling Mill ‘a man out of place’ on the hustings Hardy brought the attention back to the debate about the philosopher’s suitability for public life, though in his awareness of Mill’s vulnerability – in his sense of Mill’s ‘perilous exposure’ – he strikes a far more sympathetic tone than many earlier commentators.

Most importantly Hardy turned John Morley’s laudatory statement – that Mill’s ‘life was true to his professions’ – into a question: what does it mean to say that a person’s life is true to their professions? It is a question which resists easy categorisations and blithe insults. It shifts the focus from public performance to motivating principles and underlying philosophies. As such, it is an excellent question to bear in mind as we consider our prospective MPs and elect our next government.

Follow Demelza on Twitter: @demelzahookway

References

[1] ‘Philosophers and Politicians’. The Saturday Review 4 Mar. 1865 (pp. 253–4).

[2] Bertrand Russell and Patricia Russell, eds. The Amberley Papers: Bertrand Russell’s Family Background. 1937. 2 vols. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1966 (p. 297, p. 470).

[3] William White. The Inner Life of the House of Commons. 2 vols. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1897 (Vol 2, p. 33).

[4] A key source for cartoons of Mill is John M. Robson’s ‘Mill in Parliament: The View from the Comic Papers’. Utilitas 2 (1990) (pp. 102–43). The article contains many of the cartoons from the periodical press which feature Mill and considers these alongside puns and verse. Robson’s very specific aim in this article is to clarify a point of political history: to establish that it was not Mill’s ‘“crochets” or “whims”, especially women’s suffrage and proportional representation, that damaged his chances for re-election in 1868, but the hardening of party allegiances’ (p. 102).

[5] Sir Leslie Ward. Forty Years of “Spy”. London: Chatto and Windus, 1915 (p. 104).

[6] John Morley. ‘John Stuart Mill’. Times Literary Supplement 18 May 1906 (pp. 173–4).