Sebastian Packham took the ‘Philosophical Britain‘ module at Queen Mary in 2015. In this post he writes about ‘Nihilism’ as a philosophical keyword.

On February 27th, 2015, there began a worldwide debate about the colour of a dress. A picture of the dress in question had appeared on social networking sites the previous day, and divided opinion as to whether it was black and blue, or white and gold. ‘Dressgate’, as the phenomenon was dubbed, evoked distinct reactions from demographics across the globe, including among the more extreme, existential crises stemming from the apparent subjective nature of reality that the picture seemed to illustrate. If we cannot know for certain something as simple as the colour of a dress, then what can we really know about anything at all? Let alone abstract concepts such as morality, religion or the purpose of life. Of course, it would be foolish to assume that such philosophical sentiment was born from a viral picture in the same year that the once mythical hoverboard is set to become a reality, rather its roots date back over two millennia, and in the late eighteenth century formed the basis for the philosophical doctrine that would come to be termed nihilism.

On February 27th, 2015, there began a worldwide debate about the colour of a dress. A picture of the dress in question had appeared on social networking sites the previous day, and divided opinion as to whether it was black and blue, or white and gold. ‘Dressgate’, as the phenomenon was dubbed, evoked distinct reactions from demographics across the globe, including among the more extreme, existential crises stemming from the apparent subjective nature of reality that the picture seemed to illustrate. If we cannot know for certain something as simple as the colour of a dress, then what can we really know about anything at all? Let alone abstract concepts such as morality, religion or the purpose of life. Of course, it would be foolish to assume that such philosophical sentiment was born from a viral picture in the same year that the once mythical hoverboard is set to become a reality, rather its roots date back over two millennia, and in the late eighteenth century formed the basis for the philosophical doctrine that would come to be termed nihilism.

From the Latin nihil, meaning nothing or ‘that which does not exist’, nihilism is the belief that all knowledge is baseless, and as such focuses on the rejection of values and constructs, including morality, religion and the inherent value of systems of government. A true nihilist would, according to Alan Pratt of the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ‘have no loyalties, and no purpose other than, perhaps, an impulse to destroy.’[1] It may come as no surprise then, that nihilism has presented a profound philosophical problem, acting as the source of plentiful debate since its inception, and that the concept is often associated with deep pessimism, used pejoratively and with negative connotations.

The thinking that underpins nihilist philosophy can be traced back to the skeptics of ancient Greece, the subjectivity with which they imbue the idea of knowledge being summed up by Demosthenes, who held that ‘what he wished to believe, that is what each man believes’.[2] Such thinking was labeled as nihilism at the end of the eighteenth century, and the word’s invention is often credited to either Jacob Obereit, F. Jenisch or Friedrich Schlegel.[3] Becoming popularized through the period’s literature, perhaps most significantly the novel Fathers and Sons by Ivan Turgenev – one of its protagonists being a staunch nihilist, the ideology began to capture the minds of contemporaries, becoming a significant influence on the work and thought of European philosophers, writers, artists and intellectuals.

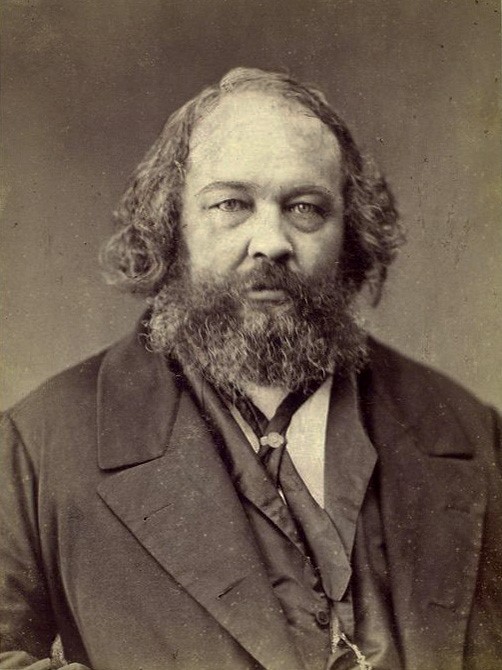

Nihilism’s focus on the rejection of the various constructs that were conducive to human culture at the time, was attractive to the European revolutionary movements that advocated rearrangement of social structures and the dismantling of existing forms of government. Such movements found a particularly strong voice in Russia as a response to the heavy handed ruling of Tsar Alexander II.[4] The nihilist ideology of the Russian revolutionary anarchist, Mikhail Bakunin, is evident in his article for the Deutsche Jahrbücher in 1842, in which he wrote ‘Let us put our trust in the eternal spirit which destroys and annihilates only because it is the unsearchable and eternally creative source of all life –the urge to destroy is also a creative urge’.[5]

As Isaiah Berlin observed, Bakunin is advocating a ‘positive nihilism’, out of which ‘there will arise naturally and spontaneously… a natural, harmonious, just order’.[6] Among supporters of the state, or upholders of the religious authority which the revolutionaries rejected, however, the understanding of nihilism was that it was a philosophy concerned purely with mindless destruction. As such, the state began to actively oppress the activity of nihilist revolutionaries,[7] and nihilism became a blanket term, carrying connotations of subversion and chaos, for anybody involved in underground political or terrorist activity.[8] Here we can observe two distinct understandings of nihilism developing – nihilism as a radical philosophy with revolutionary potential, and nihilism as a destructive philosophy geared towards reversing progress. Both perspectives were tackled by Friedrich Nietsche, who in his work Will to Power, described nihilism as ‘a catastrophe…that is growing from decade to decade: restlessly, violently, headlong’.[9] Upon such a spread of nihilism, however, he remarked ‘whether [man] becomes a master of this crisis, is a question of his strength. It is possible…’[10] For Nietsche then, nihilism could pave the way either to chaos or to a new moral order, and it is uncertainty as to which path nihilism leads that keeps the topic so divisive and widely debated.

The same way that Russian nihilism had been a reaction to various social ills in the nineteenth century, expressions of nihilism across Britain throughout the last century can also, arguably, be correlated with periods of significant adversity or discontent. The wave of riots that swept the UK in 2011, which saw moral nihilism enacted through mass looting, arson, violence and clashes with police, are often attributed to a plethora of social ills including racism, classism and a feeling of hopelessness as a result of economic downturn and an ever growing divide between the rich and the poor.[11]

Let down by society, it is argued, the rioters turned to rejection of moral authority and instead turned to violence and destruction to establish their position. Similarly, it can be argued that the anti-austerity protests the previous year were triggered by those involved, feeling betrayed, rejecting the authority of government and instead seeking to impose their will through violence –[12], effectively adopting Bakunin’s model of revolutionary nihilism.

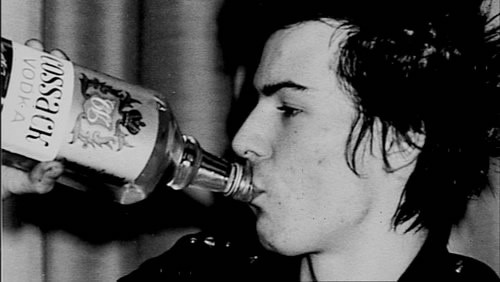

Similar preconditions, along with the very real prospect of nuclear war have been put forward as causes for the wave of nihilism that swept the UK in the form of the punk subculture. The hedonism, crass behavior and drug abuse of those such as John ‘Sid Vicious’ Beverly of the Sex Pistols[13] acted as a means of rejecting moral authority and implementing a new way of living. Beverly popularized the phrase ‘no future’ (the original title for the single God Save the Queen)[14] during this period, which articulates the nihilistic tendencies of those involved with the subculture.

Such theories as to why nihilism has been expressed the way it has across Britain in the last century are not universal however, and with each of the aforementioned movements or incidences there has been a school of thought that places them in the broader context of moral decline. The liberalization of society, such as the prohibition of corporal punishment, it is argued, has restricted the means with which people can be disciplined, leading to a lack of respect for authority. The moral decline argument is often coupled with decline in religious belief, owing largely to Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. Such an argument perhaps holds most weight with the moral nihilism advocated by Richard Dawkins in The God Delusion, in which he writes ‘do you really mean to tell me the only reason you try to be good is to gain God’s approval and reward…?’[15] Here, Dawkins is rejecting the notion of absolute morality, and in doing so imbues morality with a new sense of meaning: if there are no moral absolutes and a subject is free to act abhorrently, the choice to act in a way they believe to be good means more than simple obedience to absolute authority.

The varying ways that nihilism has been understood and expressed can act as a means through which we can read the past and to understand the collective minds of the cultures that occupied it. An extreme philosophy, nihilism often picks up a pace in extreme times. Whether you believe it is a reaction to, or a precursor of discontent and social ills, its existence nevertheless demonstrates the extremity of emotion felt at the times it is rife. What relevance though, does the concept of nihilism hold in the present day? Can a philosophy centered around rejection really bring anything to human culture? Does nihilism represent a crisis for humanity, or can we use it as a way to remove absolutes and create our own meaning or ways of living? Is the inception and propagation of nihilism indicative of a desire for progress, or does it highlight moral decline in society? As a nihilist, I’d tell you there’s no way we can really know, but what we can be sure of is that a brief discussion of the concept’s history can help to prepare us for the next time an inanimate objects shakes the foundations of our reality.

Further Reading

Shane Weller, Modernism and Nihilism, (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011)

Karl Löwith, Martin Heidegger and European Nihilism, (New York: Columbia University press, 1995)

Ofelia Schutte, Beyond Nihilism: Nietzsche Without Masks, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984)

Keith Ansell-Pearson, An Introduction to Nietzsche as a Political Thinker: The Perfect Nihilist, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994)

Friedrich Nietzsche, The Will to Power, (New York: Vintage Books, 1968)

Mikhail Bakunin, God and the State, (New York: Dover, 1970)

Peter C Pozefsky, The Nihilist Imagination: Dmitrii Pisarev and the cultural origins of Russian Radicalism (1860-1868), (New York: Peter Lang International Academic Publishers, 2003)

Bibliography

Books and Articles

Karen Leslie Carr, The Banalization of Nihilism: Twentieth Century Responses to Meaninglessness, (New York: State University of New York Press, 1992).

Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion, (London: Bantam Press, 2006).

Michael Gillespie, Nihilism Before Nietzche, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994).

Ronald Hingley, Nihilists: Russian Radicals and Revolutionaries in the Reign of Alexander II, (New York: Delacorte Press, 1969).

Paul Thomas, Karl Marx and the Anarchists Library Editions: Political Science, Volume 60, (London: Routledge, 2009).

Databases and E-Resources

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-14483149

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-14483149

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-14483149

References

[1] http://www.iep.utm.edu/nihilism/

[2] http://www.iep.utm.edu/nihilism/

[3] Karen Leslie Carr, The Banalization of Nihilism: Twentieth Century Responses to Meaninglessness, (New York: State University of New York Press, 1992), p.13.

[4] Ronald Hingley, Nihilists: Russian Radicals and Revolutionaries in the Reign of Alexander II, (New York: Delacorte Press, 1969), p.15.

[5] Paul Thomas, Karl Marx and the Anarchists Library Editions: Political Science, Volume 60, (London: Routledge, 2009), p.289.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Michael Gillespie, Nihilism Before Nietzche, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), p.163.

[8] www.iep.utm.edu/nihilism/

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-14483149 [Accessed 28/2/2015].

[12] http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,2036392,00.html [Accessed 28/2/2015].

[13] Michael T. Thornhill, ‘Vicious, Sid (1957–1979)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011 [http://0-www.oxforddnb.com.catalogue.ulrls.lon.ac.uk/view/article/40644, [accessed 1/3/2015].

[14] Ibid.

[15] Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion, (London: Bantam Press, 2006), p.259.