In this post, Shannon Gadd, who took the ‘Philosophical Britain‘ module at Queen Mary in 2015, writes about ‘Surrealism’ as a philosophical keyword.

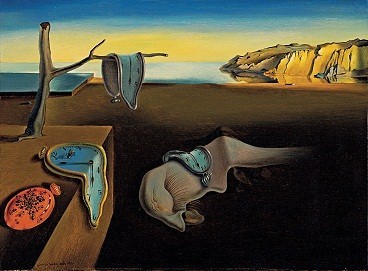

Stereotypical views of life tend to focus on the negative, adopting words such as dull, logical and ordinary. There does however seem to be an alternative to this routine monotony which is found in the philosophy of surrealism. Rejecting the rational, contradicting the conscious and negating the normal, surrealists adopt a view of life that seeks to liberate the imagination and study the unconscious and its dream like state. It is normally studied through the artistic movement that erupted in France in the 1920s.

Surrealism is, however, more than just an artistic movement. It is more than an aesthetic. There is a strong political undertone to surrealism that seeks to reject the rational and moral obligations of ordinary life. As Michael Richardson succinctly puts, surrealism is not about conjuring up that which can be defined and magical and unusual. Rather, surrealism looks for the points of contact and conjunctions between different realms of existence.[1] It is also important to note that the surrealist is not incapable of rational thought just because he rejects it. The drawing upon irrational thought and the focus on the subconscious only allows the surrealist to promote himself as a revolutionary thinker. Simply, surrealism would condemn that which puts artistic accomplishment and aestheticism before revolutionary spirit and thought.[2]

History

1920s France was a hot bed for art and poetry. However ‘surrealism’, or surréalisme, entered the French over a decade earlier. The word was first used in the preface to Guillaume Apollinaire’s play Les Mamelles de Tirésias (1903) in which he claims to “forge the surreal adjective.”[3] Guillaume Apollinaire The word was meant to represent something beyond reality and something that could not be imagined. In Apollinaire’s own words, think of Surrealism as such: When man “wished to imitate his own walk, he created the wheel; he thus made super-realism without knowing he did.”[4]

Surrealism is said to have its roots in the earlier artistic movement, Dadaism. The Dadaist painter Francis Picabia claims that “Dada is the groundwork to abstract art and sound poetry, a starting point for art and…laid the foundation for surrealism”.[5] Simply, Dadaism was the belief that rational thought and bourgeoisie values were the source of world conflict. Surrealism began to grow as a force of its own through the aid of André Breton and Philippe Soupault who published what is now known as the first Surrealist work, The Magnetic Fields in 1920. It distinguished itself from other movements by rejecting the ordinary and relying on the liberation of the imagination, a focus on dreams and the unconscious and tending towards the peculiar. Sigmund Freud’s ideas were particularly influential here. The aim of this movement was hoped to be revolutionary, freeing people from the false rationality of life. In 1924, Breton published the Surrealist Manifesto which outlined the purpose of the movement as one to examine the real functioning of thought outside of reason and moral preoccupation.

British Surrealism

While surrealist activity is thought to be largely French, Surrealism entered the British philosophical and political sphere in 1936 with the formation of the British Surrealist Group and the opening of the International Surrealist Exhibition. However it has been claimed that British surrealism remained a localised movement in the 1930s and 1940s limited to London and Birmingham. The London movement quickly subsided in 1947 with the merging of London group with the French both physically and ideologically. Conroy Maddox and John Melville were the key figures of the The Birmingham Surrealists. The Birmingham Surrealists were somewhat independent of the London group, refusing their art to be shown at the Surrealist Exhibition and rejecting the London group’s anti-surrealist tendencies.

It seems that British Surrealism was rather confined to the academic sphere of life, but an area of surrealist thought that has often been overlooked is its link to film and theatre. What could be a greater form of escapism than film? Surrealist film sought to disorient the audience and break down the logical thinking in the mind.[6] Film was a medium for derealising the world, to nullify the norm.

It is difficult to talk of surrealism as a modern movement, or even to relate it to the modern day as there does not seem to be any distinct surrealist ideologies in the present day. Historians have argued that the death of André Breton in 1966 marked the end of Surrealism as an organized movement whilst other historians have marked Salvador Dalí’s death in 1989 as the death of surrealism.[7] Surrealism as a political force in Britain subsided much earlier than the rest of Europe, with Poland seeing surrealist revolutionary tendencies all the way through the 1980s, with the anarchic group the Orange Alternative. It must be asked then whether surrealism as a movement, as an idea, was extremely localised.

Indeed, the political and revolutionary nature of surrealism seems to have declined more recently. Therefore it must be asked what legacy the early surrealist movement left. Is surrealism present in modern thought and culture? Modern political anarchism and revolutionary thought is certainly a descendent of the surrealist movement. I would argue that while Surrealism’s influence did indeed lessen after the 1960s, its legacy in political anarchism and surrealist humour have remained until the present day. There is an undeniable influence of surrealism in British comedy as early as the 1940s with the absurdist comedian Spike Milligan. However, surrealist humour found its form in Britain much later, as seen with the eruption of alternative comedy scene in the 1980s through the popular television show The Comedy Strip Presents, spawning comedians such as Rik Mayall, Ben Elton and Alexei Sayle. Perhaps, then, surrealism and satire became more closely intertwined as opposed to the idea of surrealism being its own strand of political and philosophical thought. The 1980s was dominated with absurdist comedy which saw television shows such as the completely absurdist Young Ones grow in popularity, as in the following extract which demonstrates the politically anarchic nature of this kind of surrealism.

Surrealist humour has remained popular up to the present day with Vic Reeves and Bob Mortimer dominating the absurd comedy scene with Shooting Stars in the 1990s. More recently, comedians such as Eddie Izzard and Noel Fielding have adopted distinctly surreal ideologies in their career. This is arguably the first time that Surrealism came into the popular and public life and arguably the first time surrealism had a real cultural impact on the masses. Previously surrealism had been confined to philosophers, academics and artists and was, somewhat, inaccessible. However the eruption of the British alternative comedy scene made surrealism accessible.

I feel like I should reject the view that Surrealism was a failed movement.[8] I also feel like I should defend surrealism and its legacy. While it did have its ‘golden age’ in the 1920s and 1930s and while it did not seem to be as strong in England as it did continentally, surrealism has indeed penetrated British public and cultural life whether consciously or unconsciously, intendedly or unintendedly. This cultural breakthrough, arguably, has spawned an era of political anarchism and perhaps renewed the interest in politics and encouraged the rejection of moral and cultural obligations. Historians have also argued that surrealism left a very great legacy in that of feminism. Due to surrealism’s inherent rejection of the conscious life and their appreciation of revolution, they battled against patriarchal institutions such as the church, the government which sought to regulate the woman. Surrealism, then, gave escape to this patriarchy and allowed for social and artistic resistance that liberated feminine imagination.

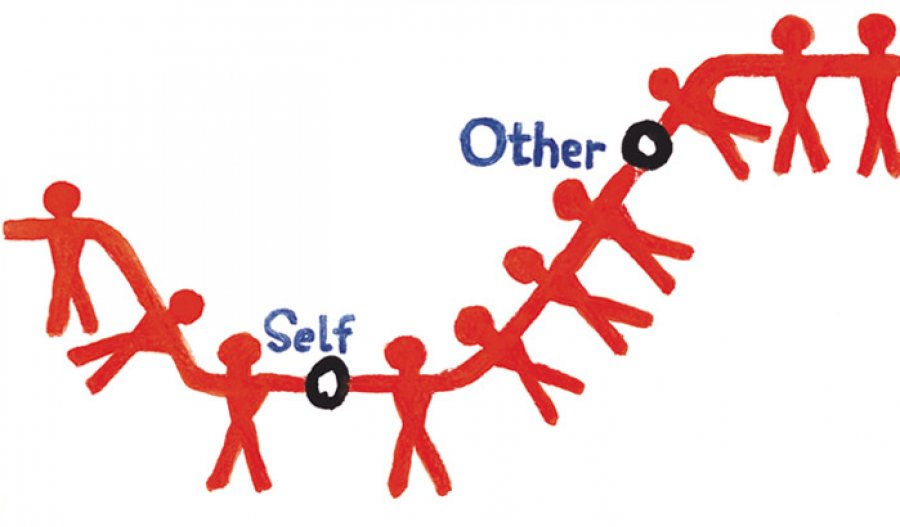

To finish, I would like to think that every time a person seeks to escape from the limitations of life or tries to relinquish the shackles of appropriateness and cultural obligation, this is a legacy created by surrealism. Every time a person rejects their physical surroundings and questions their government, they have surrealist ideas in mind.

Further Reading:

Caws, Mary Ann, Surrealism (London: Phaidon, 2010).

Harris, S., Surrealist art and thought in the 1930’s: art, politics, and the psyche (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Lomas, D., The haunted self: surrealism, psychoanalysis, subjectivity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000).

Matthews, J. H., Surrealism and Film (Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1971).

Parkinson, G., Surrealism and Politics: Interpretation, Determinism and Art History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006).

Bibliography

Alexandrian, Sarane, Surrealist Art (New York: Praeger, 1970).

Matthews, J. H., Surrealism and Film (Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1971).

Picabia, Francis (ed.), I Am a Beautiful Monster: Poetry, Prose, and Provocation (Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2007).

Richardson, Michael, Surrealism and Cinema (Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2006).

Rosemont, Penelope, ‘All My Names Know Your Leap: Surrealist Women and Their Challenge’, in Penelope Rosemont, Surrealist Women: An International Anthology: The surrealist revolution series (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1998).

Guillaume Apollinaire, Les Mamelles de Tirésias; Preface. 1917 [ONLINE]

Modernist Journals Project. The Egoist, vol. 5, no. 4 (1918). [ONLINE]

References

[1] Michael Richardson, Surrealism and Cinema (Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2006), p. 3.

[2] J. H. Matthews, Surrealism and Film (Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1971), p. 34.

[3] Guillaume Apollinaire, Les Mamelles de Tirésias; Preface. 1917 [ONLINE] Available at: http://wikilivres.ca/wiki/Les_Mamelles_de_Tir%C3%A9sias/Pr%C3%A9face. [Accessed 01 March 15].

[4] Modernist Journals Project. The Egoist, vol. 5, no. 4 (1918). [ONLINE] Available at: http://modjourn.org/render.php?view=mjp_object&id=1308747513821877. [Accessed 01 March 15].

[5] Francis Picabia (ed.), I Am a Beautiful Monster: Poetry, Prose, and Provocation (Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2007), p. 1.

[6] Matthews, Surrealism and film, p. 89.

[7] Sarane Alexandrian, Surrealist Art (New York: Praeger, 1970), p. 232.

[8] Rosemont, Penelope, “All My Names Know Yopur Leap: Surrealist Women & Their Challenge”, in Penelope Rosemont, Surrealist Women: An International Anthology: The surrealist revolution series (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1998).