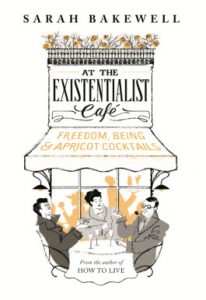

Richard Ashcroft is a philosopher and ethicist. He is Professor of Bioethics in the School of Law at Queen Mary University of London. Here he reviews Sarah Bakewell’s book At the Existentialist Café: Freedom, Being, and Apricot Cocktails (Chatto & Windus, 2016) for the Cultural History of Philosophy Blog.

As a teenager I began to take an interest in philosophy for some of the usual reasons: uncertainty about the existence of God, doubt about the sort of person I was or wanted to be, puzzlement about my studies, utter confusion about sexuality. I took myself fairly regularly to the public library in search of enlightenment.

After getting bored by E. R. Emmet’s Pelican paperback, Learning to Philosophise – I really wasn’t that bothered by the existence of tables, but I was bothered that people might bother about that – I had fun with A. J. Ayer’s punk rock classic, Language, Truth and Logic, and then fell off the deep end into Nietzsche’s abyss through R. J. Hollingdale’s biography. Yet there was something a bit too challenging about Nietzsche. He was too elusive. Even the greatest hits (“God is dead…”) slipped through my fingers when I tried to pick them up and examine them. What Nietzsche did give you was a sort of borrowed dangerousness. Sticking a copy of Thus Spake Zarathustra in your pocket gave you instantly the air of an Intellectual, even if you didn’t know what it was on about, in part because no one else did either, but it gave everyone something to react to. Nietzsche would have something to say about this, no doubt.

After getting bored by E. R. Emmet’s Pelican paperback, Learning to Philosophise – I really wasn’t that bothered by the existence of tables, but I was bothered that people might bother about that – I had fun with A. J. Ayer’s punk rock classic, Language, Truth and Logic, and then fell off the deep end into Nietzsche’s abyss through R. J. Hollingdale’s biography. Yet there was something a bit too challenging about Nietzsche. He was too elusive. Even the greatest hits (“God is dead…”) slipped through my fingers when I tried to pick them up and examine them. What Nietzsche did give you was a sort of borrowed dangerousness. Sticking a copy of Thus Spake Zarathustra in your pocket gave you instantly the air of an Intellectual, even if you didn’t know what it was on about, in part because no one else did either, but it gave everyone something to react to. Nietzsche would have something to say about this, no doubt.

Yet it was only when I encountered the Existentialists that I began to get a sense of what philosophy might really be and how one might practically do – indeed, live – it. My route into Existentialism was through Beckett, but I quickly moved into the main writings of Camus, Sartre, de Beauvoir and eventually Heidegger as I passed through my late teens and into my twenties. By the time I began to study philosophy (as part of History and Philosophy of Science) I had become aware that the Existentialists were rather out of fashion. Derrida and Foucault were now the names to drop, though of course they had their own debts to Existentialism. The professional philosophers I was taught by largely, though not exclusively, scorned this stuff (analytic rigour or Fenland parochialism? You decide). But in the wider circle of people who were interested in philosophy, who stuck paperbacks in their pockets and got into passionate and futile arguments in pubs and parties and over endless chocolate biscuits, the Existentialists were still current.

My reason for this excursion through memoir is to underline a thing which Sarah Bakewell’s study of the lives of the Existentialists highlights: the cultural importance of Sartre and company, and the autobiographical importance of these thinkers in the lives of many readers who grew up in the post-war period. Philosophy was current. People talked about it. People had fannish relations with philosophers; if you liked Sartre, you weren’t supposed to like Camus. For men particularly Simone de Beauvoir was the Yoko Ono of thought. The pop analogy is deliberate; for much of this coincides with the rise of pop and rock culture, and the emergence of the Teenager.

Much of the language of teenage self-fashioning and evaluation of pop trends is drawn directly from Existentialism – either directly or through writers such as Colin Wilson. Consider the lyrics of The Who, for instance, which are deeply engaged with questions of authenticity, honesty and truth in a very Sartrean vein; the same can be said of the Sex Pistols in a more refracted and distilled form.

Existentialism mediates between the ordinary developmental crisis of trying to become an adult person in one’s own right and the more specific crisis of doing so in a consumer society which both prioritises and pathologises individualism. Another feature of the postwar teenage experience is that “the kids” know something the adults don’t, that real invention and innovation come from youth and inexperience, and that the world as we find it is corrupt and needs to be overcome through youthful energy. Again, these are very Existentialist notions about finding one’s authentic project in world into which we are thrown, but which we can remake on our own terms, not accepting the rules as given as being binding upon us morally, but only as constraints to be overcome.

Bakewell’s book is terrific – beautifully written, and elegant in its precise and concise portraits of the leading figures in the European Existentialist movement, their engagements – with thought and with each other – and the historical circumstances through which they moved. She is very fair to her cast, but does admit to her preferences. She is acute and tough-minded when it comes to her appraisals of their various political engagements (she’s especially good on Heidegger, but the arguments between Camus, Merleau-Ponty and Sartre are also well treated). One thing which appeals to Bakewell (and to me) is the relative prominence of women as Existentialist philosophers, and arguably the most abiding influence of Existentialist philosophy as such is in feminism, and I must admit that the only work of the Existentialists I would now want to go back to re-read is The Second Sex.

Bakewell’s book is terrific – beautifully written, and elegant in its precise and concise portraits of the leading figures in the European Existentialist movement, their engagements – with thought and with each other – and the historical circumstances through which they moved. She is very fair to her cast, but does admit to her preferences. She is acute and tough-minded when it comes to her appraisals of their various political engagements (she’s especially good on Heidegger, but the arguments between Camus, Merleau-Ponty and Sartre are also well treated). One thing which appeals to Bakewell (and to me) is the relative prominence of women as Existentialist philosophers, and arguably the most abiding influence of Existentialist philosophy as such is in feminism, and I must admit that the only work of the Existentialists I would now want to go back to re-read is The Second Sex.

Writing and publishing a popular book about philosophers who were (are?) popular calls for comment in its own right. Bakewell’s book sits alongside Andy Martin’s The Boxer and the Goalkeeper: Sartre vs Camus as a popular exposition of the ideas and lives of the Existentialists. It also sits alongside Bakewell’s study of Montaigne, How To Live: A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer. Stuart Jeffries has just published a group biography of German humourists The Frankfurt School (The Grand Hotel Abyss). And of course any visit to a bookshop will find a section on philosophy, much of which is devoted to a few Penguin classics, some popularisations of particular philosophers’ works, and books from the ever expanding “School of Life” books and the omnipresent Alain de Botton.

The standard philosopher’s view of all this might be that most of these are not “real” philosophy, being neither rigorous academic texts nor much connected to current research in the field. The standard non-philosopher’s view of that would be that that’s so much the worse for academic philosophy. I think reading Bakewell allows a more nuanced view to emerge. It shows that the “academic” and the “popular”, and indeed the “text” and the “life” can come together, but that it takes a rather specific historical conjuncture to occur for this to happen. Crudely put: while popularisation succeeds because there is a felt want for some kinds of “teaching” about life and its meanings and purposes which is never wholly out of fashion, it takes a lot more for work in professional philosophy (inside the academy or elsewhere) to become popular in its own right.

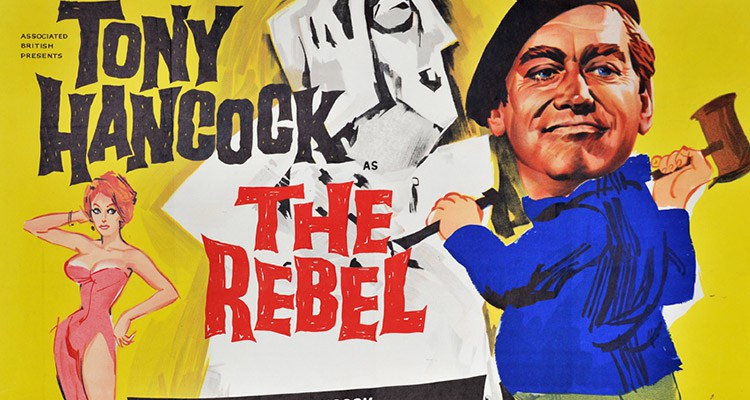

In the case of Sartre and company, they achieved a certain level of “cool” at a time when “being cool” was coming into focus; they danced, they drank, they published, they fought, and, in due course, they became so current and recognisable that Tony Hancock could make a film satirising and admiring them and their fans and Monty Python could do a skit in which two of their redoubtable Pepperpot ladies called on Sartre in Paris to ask him about a point of metaphysics, and millions of viewers would be in on the joke.

Some of this is probably mere historical happenstance. But the hook which enables this popularity is the engagement of this philosophy with the things of life itself – you don’t just philosophise and then go dancing. You philosophise about the dancing. And you dance philosophically.

Follow RIchard Ashcroft on Twitter: @qmulbioethics

Read more about Existentialism on the Cultural History of Philosophy Blog