Dr. John Duncan is the director of the Ethics, Society, and Law program at Trinity College in the University of Toronto, and the founding president of the society for the study of Existential and Phenomenological Theory and Culture, as well as its journal PhaenEx. He gained his BA and MA in philosophy from Carleton University, and his PhD in social and political thought from York University. John works on a variety of issues including existentialism, the history of philosophy, and peace and conflict studies.

Dr. John Duncan is the director of the Ethics, Society, and Law program at Trinity College in the University of Toronto, and the founding president of the society for the study of Existential and Phenomenological Theory and Culture, as well as its journal PhaenEx. He gained his BA and MA in philosophy from Carleton University, and his PhD in social and political thought from York University. John works on a variety of issues including existentialism, the history of philosophy, and peace and conflict studies.

In this post for the Cultural History of Philosophy blog, John works with Jean-Paul Sartre’s radical understanding of freedom of choice to critically interpret Kanye West’s controversial claim that slavery is a choice.

On May 1, 2018, in an interview on the popular Los Angeles-based tabloid news website TMZ, the incredibly successful and controversial African-American hip-hop artist and entrepreneur Kanye West said: “When you hear about slavery for 400 years—for 400 years? That sounds like a choice.” During the interview, about 3 minutes of which are on the TMZ Newsroom webpage, Kanye also characterises African-American slavery as mental imprisonment, and brings up his sense of the importance of freedom, his dislike for being categorised, and his love for U.S. President Donald Trump. TMZ senior producer Van Lathan fires back at Kanye, calling his remarks thoughtless and offensive.

It is unclear what Kanye meant, but the incident quickly became headline news, followed by a barrage of critical replies on social media and in the opinion sections of newspapers. The theme of the replies is perhaps best represented in a Tweet by Symone D. Sanders (CNN political commentator, progressive political strategist, and national press secretary for the 2016 Bernie Sanders U.S. presidential campaign), in which she wrote: “I am disgusted … Also (I can’t believe I have to say this): Slavery was far from a choice.”

However, there is at least one important respect in which slavery was a choice—the choice made by white people.

The philosopher who dealt most with the role of choice in situations of oppression such as slavery was the influential 20th century French public intellectual, Jean-Paul Sartre, who argued that human beings always have free choice. There are a couple of ways in which a reader of Sartre could argue that slavery is a choice: one, though radically incomplete, depends largely on the claim that slaves always could have resisted—this is likely closest to what Kanye meant—while another is the much more complete sense in which slavery was the choice of the white population, just as racism continues to be its choice. It is worth working our way from the former incomplete argument, to the latter more complete argument, and doing so within the context of the Sartrean logic of choice.

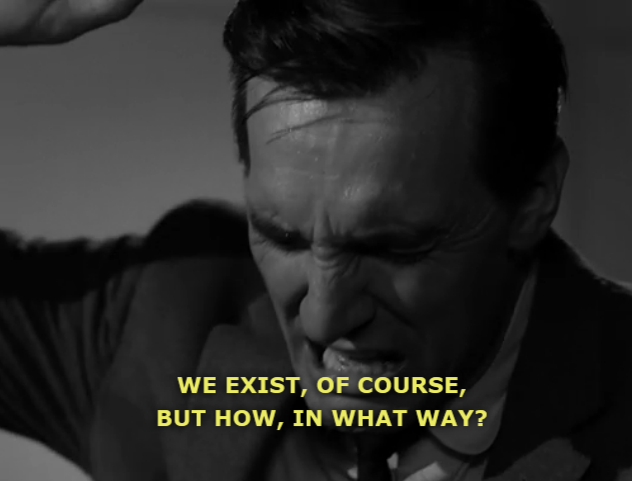

Sartre argued that even under extreme situations of oppression, including torture, individuals make free choices.[i] To understand this radical claim, we may contrast the torture of a human with the torture of a robot.

Except in science fiction, no amount of torture will make a robot choose to comply with demands inconsistent with its programming. A robot is a machine. Violent force may damage a machine, but it cannot make a machine choose anything, certainly not behaviour inconsistent with its programing. Some proponents of artificial intelligence may disagree, but their argument that robotic self-driving vehicles, for example, are safer than human-driven vehicles is based partly on the premise that the robotic vehicle’s programming does not allow it to choose to drive unsafely. Unlike a human driver who may choose to look at a mobile devise instead of the road, robots do what they are programmed to do. Indeed, as happens all too frequently, a human driver—but not a robotic vehicle—may choose to run down pedestrians deliberately, as Alek Minassian is alleged to have done, killing 10, in Toronto in April of 2018.

The goal of torture, which is a war crime that many are dismayed to be dealing with in the 21st century, is to make conditions for the victim so horrible that the choice not to comply with the torturer’s demands becomes more unbearable than the choice to comply—the torturer manipulates victims in order to get them to make the demanded choice. But the application of violent force to a human is not effective in a simple mechanical way. Whereas the right use of force to turn a functioning tap cannot fail to make water flow from it, torture can fail to get a victim to make the demanded choice. A human may choose resistance to the death, for example. And although force cannot make a robot choose anything, the right reprograming cannot fail to change its behaviour. Machines—neither simple ones like taps, nor complex ones like self-driving vehicles—simply do not make choices.

Of course, we cannot throw off oppressors by the mere exercise of choice. Lacking the power to overcome them, we are largely at their mercy. But at each moment we choose to endure, to resist, to plot, or to succumb. Indeed, it is often inspiring to learn about the exercise of choice in situations with virtually no liberty. Such choices seem to mark the near side of the limit of what it is to be a human being.

Likely, Kanye meant to say that because slavery existed for so long—“for 400 years”—slaves themselves must have too often failed to choose resistance. However, as many of those who reproached Kanye pointed out, slaves certainly exercised their fundamental freedom of choice and resisted in countless creative ways, great and small.

Readers of Sartre will recognize universal humanity in the freedom of choice that slaves retain, and in its exercise, however minimal, in situations with little liberty. Crucially important, in this respect, is the notion that each and every human being is always fundamentally his or her own choice-maker. Because we may always choose how to deal with what befalls us, we have agency in the last instance.

Unfortunately, when one chooses resistance within social structures enforced by violence, like slavery, one also chooses the risk of being beaten or lynched. Thus, although the choice to resist is real, and should be honoured, its outcome may have no impact on the social structures of oppression.

One might try to argue that because choosing resistance did not overcome slavery for many years, slavery ended up being the unwelcome result of the choices of many slaves. Although this is not likely what Kanye meant, the idea that slavery is the result of a choice that failed to liberate does raise an important question: why did resistance often fail to bring liberation?

The answer to that question is rooted in the fact that the freedom of choice that seems to be unique to humans includes the possibility of choosing to oppress others. Thus, in the case of slavery—and in the related case of racism, which is still with us—it is the white population that has chosen reprehensibly. Because the white population has benefited from the social structures of slavery and racism it has chosen to conform to those structures, or, at least, not to remove them. Not blacks and the fear of the costs of resistance, but whites and the promise of the rewards of conformity, have failed to end slavery and racism. In this sense, slavery and racism are indeed choices, both the white population’s choices to preserve dominance and privilege, and choices that apologists rationalize on the grounds of assumed superiority, promoting slavery and racism behind veils of natural necessity, and defending them behind lines of institutional power. The targets of Sartre’s critical interventions were precisely these kinds of failures to choose freedom for all.

We may try to interpret Kanye as having meant to highlight the agency of the victims of slavery—that they were not agency-less victims—but although readers of Sartre can agree with that much, they cannot agree that the responsibility for slavery lies with the victims and their agency rather than with the white population and its rationalisations and power.

During the history of slavery the white population’s choices were brutally violent; more recently they have been largely pacified and less direct, as when we fail to assume responsibility for structures from which we continue to benefit at the expense of others. Although this is not likely what Kanye meant, the history of resistance to slavery should encourage the privileged to stop making racism a choice.

[i] Sartre, Jean-Paul. Being and Nothingness: A Phenomenological Essay on Ontology. Trans. Hazel Barnes. New York: Washington Square Press, 1956. Page 649.

has served to increase the

has served to increase the