Isabel Overton took the ‘Philosophical Britain‘ module at Queen Mary in 2016. In this post she writes about ‘common sense’ as a philosophical keyword.

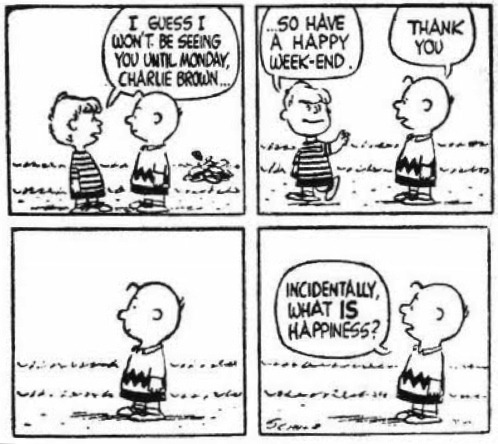

As a result of studying in one of the most expensive cities in the world, upon moving to London in September 2013 I found myself working part time in the supermarket chain Waitrose. Located in a particularly affluent area of London it boasted a continuous stream of business professionals and upper middle class families. Working in such an environment it is no surprise that I have been witness and recipient of many ‘unique’ queries. Whilst some have provided vast entertainment during an otherwise tedious shift (I once had a man ask me where we kept the ‘premium houmous’) others have been baffling in their lack of what we would call ‘common sense’. It would seem that many people, so drained from their fast paced city lives, seem to have no energy left to try and manoeuvre the minor speed bumps they may face when doing a food shop. I’m sure i’m not alone in being familiar with the phrase ‘use your common sense’, but how productive are we actually being when urging someone to tap into their inner instinct. Furthermore, where does the term ‘common sense’ stem from, and how common, or sensible, is it?

Greek philosopher Aristotle coined the term ‘common sense’ to describe a sense that unified all five human senses, such as sight and smell, allowing humans and animals to distinguish multiple senses within the same object. This came in response to a theory put forward by Plato that all senses worked individually from one another but were then integrated within the soul where an active thinking process took place, making the senses instruments of the thinking part of man. In Plato’s view, the senses were not integrated at the level of perception, but at the level of thought and thus the unifying sense was not actually a kind of ‘sense’ at all. Aristotle on the other hand, attributed the common sense to animals and humans alike, but believing animals could not think rationally, moved the act of perception out of Plato’s rational thinking soul and into the sensus communis, which was something like thinking and something like a sense, but not rational. He also located it within the heart, as he saw this as the master organ.[1]

“Good sense is, of all things among men, the most equally distributed; for every one thinks himself so abundantly provided with it”[2]

– Rene Descartes, Discourse on Method

French Philosopher Rene Descartes

Contemporary definition can be summed up as the basic ability to judge and perceive things shared by the majority of the population. Father of modern western philosophy, French philosopher Rene Descartes, in Discourse on Method established this when he stated that everyone had a similar and sufficient amount of common sense. He went on to claim however, that it was rarely used well and he called for a skeptical logical method to follow, warning against over reliance upon common sense.

During the Enlightenment common sense came to be seen more favourably as a result of works by philosophers such as religiously trained Scottish philosopher Thomas Reid. Often described as a ‘common sense philosopher’ Reid developed a philosophical perspective that provided common sense as the source of justification for certain philosophical knowledge. Reid wrote in response to the increase in scepticism put forward by philosophers such as David Hume, who held an empiricist view towards the theory of ideas, arguing that reason and knowledge were only developed through experience or through active research.[3] Reid, alongside other like-minded philosophers including Dugald Stewart and James Beattie, formed the Scottish School of Common Sense, arguing that common sense beliefs automatically governed human lives and thought. This theory became popular in England, France and America during the early nineteenth century, before losing popularity in the latter part of the period.

Political philosopher Thomas Paine

In terms of American influence Reid’s philosophy was pervasive during the American Revolution. England born political philosopher and writer Thomas Paine was a key advocate of common sense realism, and used it to advocate American independence. Published in 1776, his highly influential pamphlet Common Sense conveyed the message that to understand the nature of politics, all it took was common sense. Selling around 150,000 copies in 1776 during a time when the rate of illiteracy was high amongst the American population, Common Sense was both a tribute to the persuasiveness of Paine’s argument and his ability to simplify complex rhetoric.[4]

In the early twentieth century British philosopher G. E. Moore developed a treatise to defend Thomas Reid’s argument titled A Defense of Common Sense, that had a profound effect on the methodology of twentieth century Anglo-American philosophy.[5] This essay listed several seemingly obvious truths including “There exists at this time a living human body which is my body” arguing against philosophers who held the idea that even ‘true’ propositions could be partially false.[6] He greatly influenced Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein who, having previously known Moore during time spent in England, was reintroduced to his work when a former student was wrestling with his response to external world skepticism. Inspired, Wittgenstein began to work on a series of remarks, eventually published posthumously as On Certainty, that proposed there must be some things exempt from doubt in order for human practices to be possible.

The philosophical debate surrounding common sense shows itself as complex and immersed with disunity, so it is important to view how modern society has taken the idea of common sense and what platforms of discussion it features in. Whilst many people take for granted what they assume to be an innate natural instinct, it seems that over the past two decades there has been an increasing documented lament over the decrease in common sense within society as a whole. In 1998 author Lori Borgman released an essay entitled The Death of Common Sense in which she remarked:

“A most reliable sage, he was credited with cultivating the ability to know when to come in out of the rain, the discovery that the early bird gets the worm and how to take the bitter with the sweet.”[7]

She then noted the decline of ‘Common Sense’s’ health in the late 1960’s when “he became infected with the If-It-Feels-Good, Do-It virus”[8]. It is unsurprising that countless idle news stories reporting the ‘misgivings’ of people who appear too incompetent to make the most basic decisions has led to such a cynical outlook on how sound societies judgment is. An example that springs to mind is the plethora of multi million pound lottery winners who spend all their money within a year only to find themselves in debt wondering where it all went wrong. This is something reiterated within psychologist and professor Jim Taylor’s article Common Sense is Neither Common nor Sense, and instead he argues for a focus on ‘reasoned sense’ as opposed to ‘common sense’.

Naturally, this perceived lack of common sense has led many to question how common it really is. According to Voltaire common sense was not so common[9] but the more accurate assumption might be to suggest it was not so commonly used in particular situations; on the down side this is not nearly as memorable. Nevertheless, education teaches us to make decisions based on careful, calculated thought, something that people lacking education fail to do. Whilst almost all people have common sense, it is usually those who are more intellectually capable that ‘fail’ to use it, at least initially, when in the process of basic problem solving. This is through over-calculating however, not under-calculating, and ultimately not an accurate measure of capability.

Educational intellect does not impact the amount of common sense people hold

Many lighthearted studies have been done that test this theory, one of the most popular being to have a child and adult solve the same simple brainteaser. Studies seem to suggest that a child is more likely to solve a simple problem faster than an adult, as their lack of knowledge disallows them to overcomplicate the problem put in front of them. An example of this is found in the short clip featured below:

This use of common sense is of course unique to brain teasers and jovial mind games, and through the course of day to day life, the majority of the population are unwittingly using their common sense concisely, whether it be to look both ways before they cross the street, or to let their coffee cool down before taking a sip.

It has been argued however, that group judgment can impair individual common sense, thus providing debate towards how significant it is when used as a means of judgment. Social theorist Stuart Chase is believed to have remarked that common sense was that which told us the world was flat, putting focus on the semantic ‘common’ in its raw sense to mean widespread, that is to say, consensus of opinion.[10]

Group judgment can impair individual thinking

In 1841 Scottish journalist Charles Mackay in Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds observed: “Men, it has been well said, think in herds; it will be seen that they go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses slowly, and one by one.”[11] It is natural for something to gain credibility the more universally it is agreed upon or known, but this does not necessarily make it right. For example, studies have shown that the commonly held belief of never waking a sleepwalker as it is dangerous is actually a myth. Whilst they may find themselves disorientated upon being woken, the act itself is not harming.[12]

Through all this we have seen the reshaping, acceptance, memorial, criticism and dissection of the term, and use of, common sense, and it is ultimately personal opinion that can decipher how prevalent an individual will view it. Some pride themselves on their developed intelligence through precision schooling, whereas others prefer to boast of their natural intelligence. All this aside, I am sure I stand in the majority when I admit that this natural guide has helped me maneuver my way out of a tricky situation on more than one occasion, and so for that I am happy to look upon it favourably as a silent guardian, justified or not.

[1]Gregoric, Pavel, Aristotle on the common sense, Word Press, https://arcaneknowledgeofthedeep.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/aristotleoncommonsense.pdf

[2] Descartes, Renes, Discourse on Method 1635, https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/descartes/1635/discourse-method.htm, [accessed 19th February, 2016]

[3] David Hume, Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, http://plato.standford.edu/entries/hume/, [accessed 15th February, 2016]

[4] Thomas Paine, History, http://www.history.com/topics/american-revolution/thomas-paine, [accessed 19th February, 2016]

[5] Philosophy of Common Sense, New World Encyclopedia, http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Philosophy_of_Common_Sense, [accessed 15th February 2016]

[6] Mattey, G. J., Common sense epistemology, UC Davis Philosophy 02, http://hume.ucdavis.edu/mattey/phi102f03/moore.html

[7] Borgman, Lori, The Death of Common Sense, http://www.loriborgman.com/1998/03/15/the-death-of-common-sense/, [accessed 15th February 2016]

[8] Ibid.

[9] Voltaire, A Pocket Philosophical Dictionary, Oxford World’s Classics, 2011

[10] Hayakawa, S. I. and Hayakawa, A. R., Language in Thought and Action, Harvest Original; 5th ed. 1991, p.18

[11] Mackay, Charles, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, Wordsworth Reference, 1995, p.xv

[12] Future, BBC, bbc.com/future/story/20120208-it-is-dangerous-to-wake-a-sleepwa, [accessed 19th February, 2016]

Further Reading

Lori Borgman, The Death of Common Sense, http://www.loriborgman.com/1998/03/15/the-death-of-common-sense/

Ian Glynn, An Anatomy of Thought: The Origin of Machinery of the Mind, (Oxford University Press, 2013)

Pavel Gregoric, Aristotle on common sense, (Oxford University Press, 2007)

S. I. Hayakawa and Alan R. Hayakawa, Language in Thought and Action, (Harvest Original; 5th ed. 1991)

Philosophy of Common Sense, New World Encyclopedia, www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Philosophy_of_Common_Sense