Zena Gainsbury took the ‘Philosophical Britain‘ module at Queen Mary in 2016. In this post she writes about ‘utilitarian’ as a keyword, from John Stuart Mill to modern fashion magazines….

(Courtesy: ImaxTree) 2014 Paris Fashion Week: Utilitarian style by (Left-Right) H&M, Isabel Marant, Balenciaga, Balmain, and Lanvin.

When flicking through Grazia magazine on a Tuesday evening (I receive the joy of this subscription in my postbox weekly) nothing puzzles me more than the use of ‘utilitarian’ against a backdrop of khaki, pockets, and wrap belts. Between reading about Taylor Swift’s squad and the trivialities of Harry Styles love life I am more than surprised to see a nod towards the utilitarians. I swiftly imagine J.S. Mill, Grazia in hand, fighting for the ‘Mind the Pay Gap Campaign’ outside the Houses of Parliament alongside the likes of Gemma Arterton. Perhaps, the use of ‘utilitarian’ amongst celebrity gossip is a product of the evolution of women’s magazines like Grazia, who now, rather than print stories focused merely on the latest popstar include informed cultural pieces. But as I scan my Grazia for a ‘normal’ use of the word ‘utilitarian’ amongst these more serious pieces on women’s rights and the plight of Syrian refugees the only use of ‘utilitarian’ is to connote a fashion trend. Such a mainstream use of ‘utilitarian’ in British popular culture seems ultimately surprising – severing the white middle class figures of Jeremy Bentham and J.S. Mill from use of the word Utilitarian seems somewhat impossible. How then, has the fashion industry appropriated its use to connote something which appears to diverge completely from the utilitarian’s intentions?

(Courtesy of Wikipedia) The utilitarian and not so fashion conscious J.S. Mill.

Although the image of J.S. Mill as utilitarian philosopher and fashion darling is an amusing and somehow pleasing image this isn’t the usual picture that the word Utilitarian (dating back to 1781 to describe Jeremy Bentham himself) evokes in philosophical uses as either adjective of noun. As a noun Utilitarian refers to ‘one who holds, advocates, or supports the doctrine of utilitarianism; one who considers utility the standard of whatever is good for man; also, a person devoted to mere utility or material interests.’[1] And, again, when used as an adjective the earliest usage, is again, attributed to Jeremy Bentham; defined as ‘Consisting in or based upon utility; that regards the greatest good or happiness of the greatest number as the chief consideration or rule of morality.’ From these definitions, however, we do not gather a complete sense of what it is, or was, to be a ‘utilitarian’.

To really grasp what it is to be, or to be described as a utilitarian in pre-20th Century Britain it is best to consult the literature of the utilitarians. Bentham formulated this ethical system in a number of his life’s works which approves, or disapproves any action according to whether it augments of diminishes ‘the two sovereign masters’ pain and pleasure. [2] ‘Utility’ itself, for Bentham, refers to the ‘property’ in any object which produces any of the following: advantage, benefit, pleasure, good, happiness or the prevention of pain in regards to the interests of the individual, or the interests of the whole community. The interest of the community is calculated by taking the ‘sum’ interest of its members. Bentham argues the case for his formulation of utilitarianism by asking the question: is there any other motive a man can have which is distinguished from the motive of utility? Perhaps there isn’t, but defining ‘utility’ becomes problematic, and many condemn Bentham’s approach as merely exemplifying hedonistic principles.

‘The Auto-Icon’ courtesy of: Existential Comics – the Utilitarian Bentham and the ‘faults’ of Utilitarianism.

The hedonism in Bentham’s approach was critiqued and redeveloped by his utilitarian successor J.S. Mill. Mill, who grew up under the influence of Bentham, criticised him for ‘neglected character in his ethics’ and a focus on ‘self-interest’ and a formidable lack of ‘inspiration’ in which Mill attempted to remedy in his formulation of the Utilitarian theory. Namely, Mill’s utilitarianism differs from Bentham’s in its emphasis on quality over quantity in regards to pleasure:

‘It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied.’[3]

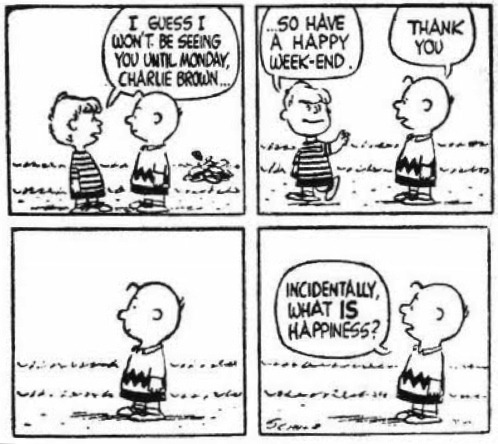

Bentham’s utilitarianism was criticised as debasing the object of human life as nothing but pleasure: ‘a doctrine worthy of swine.’ Mill tackles this criticism of Bentham by arguing that a beast’s pleasures do not satisfy a human being’s conception of happiness; and goes so far as to argue that ‘few human creatures would consent to be changed into any of the lower animals, for a promise of the fullest allowance of a beast’s pleasures’ and thus making a distinction between human and animal pleasures. Mill justifies this by suggesting that the possession of higher faculties in humans entails a greater measure of happiness for fulfilment, and as such, the fulfilment of a beast’s pleasures for a human provides no fulfilment, or pleasure, at all.

(Courtesy: Grazia 29th Feb 2016) ‘Fashion Utilitarianism’ in magazines included in a report on London Fashion Week.

In 20th and 21st Century philosophy this is problematic – Mill’s reference to ‘lower pleasures’ ridicules those with lower mental capacities who Peter Singer infers as ‘a person with an intellectual disability.’[4] It is interesting here to go back to what I will call ‘Fashion Utilitarianism’ – what end of the scale would Mill propose that this was situated? Looking perhaps at the catwalk of Paris, Madrid or London, maybe these would be considered as ‘higher pleasures’ alongside other privileged activities including opera and theatre. What about high-street ‘Fashion Utilitarianism’? I imagine that Primark sits at the bottom of Mill’s scale. Or is the consideration and pleasure taken in choosing agreeable clothing whether it is off an Essex high street or hot off the Versace catwalk a higher pleasure in itself? The problematic subjectivity inherent in both Mill and Bentham’s utilitarianism is clear here.

Peter Singer’s approach to utilitarianism is inspired by his vegetarianism and animal rights activism which makes his ‘preference’ utilitarianism more inclusive. A case that demonstrates this inclusiveness in Singer’s ethics is included in his article Famine, Affluence and Morality (1972).[5] Singer, writing after the cyclone in Bangladesh in 1971, argued that physical proximity should not be a factor when establishing one’s moral obligations to others. He argues that it makes no difference whether he helps his neighbour or someone whose name he will never know and in essence compromising the relationship between duty and charity. Hence, Singer’s utilitarian approach proposes that any act becomes duty if it will either prevent more pain that it causes or cause more happiness than it prevents. But how can this apply to fashion? It seems as if ‘Fashion Utilitarianism’ has modelled its utilitarian approach even further from Mill, Bentham and Singer’s definitions of a utilitarian ethics.

(Courtesy of ASOS) – Fashion Utilitarianism and Utility as shown on one of the leading fashion retailer’s site.

The only thing that I can see relating to these khaki adorned, boiler suit and pocket embellished page spreads is that word ‘utility’ of which utilitarianism and utilitarian derive. The other common factor that arises when looking through these glossies is the intertwining and juxtaposed use of the words ‘utilitarian’ and ‘military’ to describe a fashion trend which seems bounds away from the ethical theory proposed by Jeremy Bentham, and later J.S Mill. Magazine writers flit between using ‘utilitarian’ to describe a look to ‘military’ two words that, when thinking about the principle of utility as the minimisation of pain and maximisation of pleasure seem exceptionally polarised terms. Maybe if we go back to the definition of the word ‘utility’ this use in the fashion industry may become clearer:

‘The fact, character, or quality of being useful or serviceable; fitness for some desirable purpose or valuable end; usefulness, serviceableness.’[6]

Here I can find links between the use ‘utility’ and ‘military’ which relate to the fashion world and illuminate the meaning of ‘Fashion Utilitarianism’. The words ‘serviceable’ and ‘usefulness’ stand out in the definition of ‘utility.’ Serviceableness as the ‘utility’ of a garment links to the use of ‘military’ interchangeably with ‘utility’ or ‘utilitarian’ – what we’re really looking at is a fashion which is easy to maintain, whether this be the look, or the garment itself (which I presume is how ‘military’ comes in). ‘Usefulness’ has a much broader spectrum of connotations than utilitarianism and hence seems to resonate much more with the fashion and designers described as ‘utilitarian’. It infers a practical look; and finally those oversized pockets seem to make sense. ‘Fashion Utilitarianism’ seems to have adopted the language of the utilitarians but arguably not the semantics. However, the evolution of the word ‘utility’ resonates with words like ‘wearability’ and ‘practicality’ which relate more obviously to fashion and hence underline how the word ‘utilitarian’ has evolved in modern use. And as for the pockets, their existence on the garment is beneficial to the wearer and serves a purpose – how very utilitarian.

References:

[1] “utilitarian, n. and adj.” OED Online. Oxford University Press, December 2015. Web. 28 February 2016.

[2] Jeremy Bentham, ‘An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation’ in Utilitarianism and Other Essays, ed. Alan Ryan (London: Penguin Classics, 1987) p. 65.

[3] J.S. Mill, ‘Utilitarianism’ in Utilitarianism and Other Essays, ed. Alan Ryan (London: Penguin Classics, 1987) p. 281.

[4] Peter Singer, Practical Ethics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993) p. 108.

[5] Peter Singer, ‘Famine, Affluence, and Morality’ in Philosophy and Public Affairs, vol. 1, no. 1 (Spring 1972), pp. 229-243 [revised edition] <http://www.utilitarian.net/singer/by/1972—-.htm> [accessed: 26/02/2016]

[6] “usefulness, n.” OED Online. Oxford University Press, December 2015. Web. 29 February 2016.

Further Reading:

Existential Comics: http://existentialcomics.com/

In Our Time ‘Utilitarianism Episode: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b05xhwqf

Jeremy Bentham, ‘An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation’ in Utilitarianism and Other Essays, ed. Alan Ryan (London: Penguin Classics, 1987)

Katie Davidson, ‘Army Green Marches Down the Runway at Paris Fashion Week’ – http://www.livingly.com/Fashion+Trend+Report/articles /jqtgypb2__3/Army+Green+Marches+Down+Runway+Paris+Fashion

J.S. Mill, ‘On Liberty’ in On Liberty and other writings (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989)

J.S. Mill, ‘Utilitarianism’ in Utilitarianism and Other Essays, ed. Alan Ryan (London: Penguin Classics, 1987)

Peter Singer, Practical Ethics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993)

Peter Singer, Rethinking Life and Death: The Collapse of our Traditional Ethics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995)