Kloe Fowler took the ‘Philosophical Britain‘ module at Queen Mary in 2015. In this post she writes about ‘Humanism’ as a philosophical keyword.

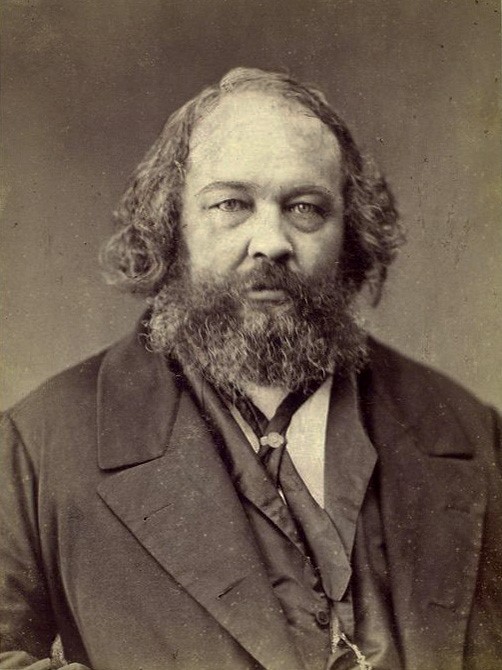

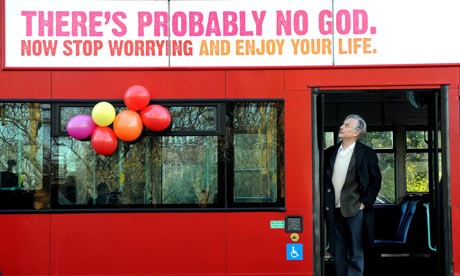

Professor Richard Dawkins on a London bus displaying the Atheist message.

Photograph: Anthony Devlin/PA

You may remember, back in 2009, seeing London buses adorned with a message reading ‘there probably is no God. Now stop worrying and enjoy your life’. The campaign was the creation of the British Humanist Association (BHA), a national Humanist group whose campaigners felt that the adverts would be a ‘reassuring antidote’ to religious adverts which ‘threaten eternal damnation’ to passengers.

The word ‘humanist’ preceded the word ‘humanism’ and began life with different connotations to its present day meaning. The word umanista was first employed in fifteenth century Italy as a slang term to describe a university professor of the studia humanitatis – the humanities. However the word ‘humanism’, in roughly the same context we speak of it today, first appeared in the German form humanismus as late as 1808.[1]

To define… humanism briefly, I would say that it is a philosophy of joyous service for the greater good of all humanity in this natural world and advocating the methods of reason, science, and democracy. – Corliss Lamont.[2]

The roots of humanist philosophy lie with the ‘fathers of humanism’. The early fourteenth-century Italian scholar, Francesco Petrarch, is often accredited with being one of the first humanists. Petrarch rejected traditional medieval scholarship in favor of a revival of Classical authors like Aristotle, Plato and Tacitus and, by doing so, Petrarch laid the foundations for a philosophy which would eventually manifest in a formally recognized movement, punctuated by national organizations and institutions.[3]

Petrarch’s ideas were developed further during the Renaissance. The word ‘Renaissance’ derives from the French term for ‘rebirth’ and it is accepted by most to mean the revival of classical scholarship and learning in Western Europe between 1400 and 1600.[4] Renaissance humanists were followers of literary, Christian humanism, where the pursuit of self-knowledge was seen as a way of getting closer to God whilst also emphasising the principles of the Holy Trinity, namely the role of Jesus as the human son of God the Father.[5] The popularity of humanism during the Renaissance can be seen in the rising popularity of humanist literature. Desiderius Erasmus, for example, emphasised the importance of Greek scholarship via manuscripts like the Adagia. The Adagia began life in 1500 as a collection of eight-hundred and eighteen Greek proverbs. By the death of Erasmus in 1536, the collection had grown to around four-hundred and fifty-one proverbs.[6]

The eighteenth century witnessed a departure from Christian humanism. The age of Enlightenment was characterised by scientific discovery, which consequently ushered in a new definition of humanism. Eighteenth century humanism became fixated on ideas of rationality, reason and the natural order. Auguste Comte, the ‘father of sociology,’ even attempted to rationalise the twelve-month Gregorian calendar by devising a new thirteen-month calendar with an extra day to worship the dead and a system for leap years. Finally, Comte proposed that each month be named after a Classical graeco-Roman scholar hence, March would become ‘Aristotle’.[7]

The philosophy of ‘Positivism’ was the brainchild of Comte. It stipulated that any attempts to prove truths about the world were futile unless they were based on sense perception or empirical scientific evidence.[8] Over time, Comte combined his Positivist ideals with existing humanist ones and embodied them in the formation of the ‘Religion of Humanity’. The Religion of Humanity was an atheistic religion which aimed to eliminate transcendence and superstition but maintain religious rituals and ethical teaching.

“On or about December 1910, human nature changed… all human reactions shifted… and when human relations change, there is at the same time a change in religion, conduct, politics and literature” – Virginia Woolf.[9]

The early disasters of the early twentieth century resulted in widespread pessimism and disillusionment in Europe. People began to identify that humanism had been unable to prevent any of the disasters which had affected them.[10] However, post-war disillusionment was endemic only to wartime and the humanist philosophy made a quick recovery, particularly among the Allied nations. In 1952, in Amsterdam, the humanist movement became formally recognised as the ‘International Humanist and Ethical Union’ (IHEU).

At around the same time, Marxist principles were brought to bear on Humanism. Karl Marx’s early writings, like The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 and The German Ideology, concentrated on Marx’s theory of ‘alienation,’ the idea that humans had lost their natural attributes and abilities as a result of living in an artificial, class-based society. In 1953 Nikita Khrushchev espoused these ideas at a party congress and consequently delivered a current of class-conscious ‘Marxist Humanism’ across Western Europe. By 1966, Erich Fromm and several other Marxist and ‘new left wing’ Humanists had outlined their world-view in An International Symposium of Socialist Humanism.

In 1961 Julian Huxley (grandson of ‘Darwin’s Bulldog’ Thomas Huxley, and brother of novelist Aldous Huxley), further consolidated the Humanist world-view by compiling works by himself and twenty-five other leading thinkers into a comprehensive volume called The Humanist Frame. Unusually, Huxley was a somewhat fanatical believer of Humanism. He viewed Humanism as a revolutionary, world-unifying philosophy. Huxley says ‘Humanism is seminal. We must learn what it means and then disseminate humanist ideas and finally inject them where possible into practical affairs as a guiding frame’.[11]

“Because humanists believe in the unity of humanity and have faith in the future of man, they have never been fanatics” – Erich Fromm.[12]

As we emerge into the twenty-first century, for the first time in history, mankind has been brought together by worldwide global problems. Issues like international security, the population explosion and the needs of third-world countries have recently begun to be addressed.[13] The international climate of humanitarian humanism has been most recently demonstrated by the global response to the ongoing Ebola epidemic in Western Africa.

However, Humanism has still not acquired the recognition it deserves. Since the millennium, western society has been dogged by the threat of terrorism. The paradoxical rise of religious fundamentalism in the Middle East not only threatens the west with disruption and violence but it also threatens the west with the internal indoctrination of its peoples. Since the Charlie Hebdo attack in Paris, reports of atrocities committed by the radical Islamic group Islamic State (IS) have appeared daily in British news. Moreover, the UK Foreign Office estimates that around four-hundred Britons have travelled to Syria to fight for IS.

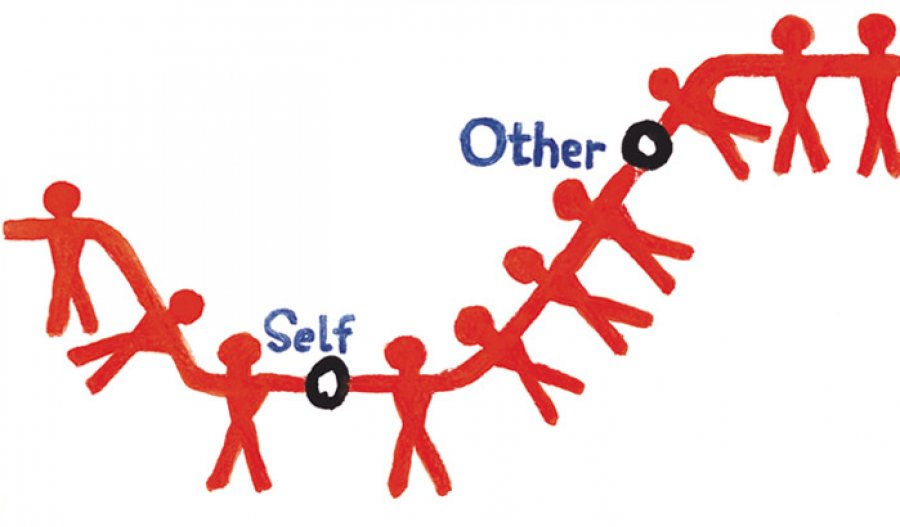

A motif which embodies the contemporary definition of Humanism (2014). Photograph: International Humanist and Ethical Union

In light of this threat it seems to me that now is the perfect time for British society to adopt the principles of humanism. The atheist, collectivist and humanitarian qualities of humanism are invaluable to a modern nation tormented by the threat of violence and radicalism. The Atheist Bus campaign was launched six years ago and the BHA has not launched a repeat campaign since. Unfortunately, the marketing department at the BHA seems to be redundant at a time when British society is desperate for the reassurance of a shared, rational belief system.

Whilst writing this post I stumbled upon a motif which was of great interest to me. To my understanding, it perfectly exemplifies our contemporary understanding of the word Humanism. It advocates knowledge, rationalism, human rights, liberty and collectivism and is contextualised by the recent Charlie Hebdo tragedy and cast in front of the universally-recognised humanist logo.

So, I will conclude with a proposal. I propose that the BHA awake from their redundancy and advocate the updated definition of Humanism. I suggest that they renew their campaign and use this motif, combined with public transport, as a vehicle for disseminating humanist ideas. With the help of evolved humanist philosophy, perhaps the East and West will one day be able to reconcile their differences in a rational and humanitarian way.

Further Reading

A. Bullock, The Humanist Tradition in the West (New York and London: W. W. Norton and Company, 1985).

N. Everitt, The Non-Existence of God (London: Routledge, 2004).

E. Fromm (ed) An International Symposium of Socialist Humanism (New York: Anchor Books, 1966).

P. O. Kristeller, Renaissance Thought and the Arts: Collected Essays (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1964).

C. Lamont, The Philosophy of Humanism, Eighth Edition (New York: Humanist Press, 1997).

J. S. Mill, Auguste Comte and Positivism (London: Trubner and Co, 1865).

L. and M. Morain, Humanism as the Next Step (Washington: The Humanist Press, 2012) (Click here to download your free copy from the American Humanist Association)

References

[1] A. Bullock, The Humanist Tradition in the West (New York and London: W. W. Norton and Company, 1985) p.12.

[2] C. Lamont, The Philosophy of Humanism, Eighth Edition (New York: Humanist Press, 1997) pp.12-13.

[3] R. Morris, ‘Petrarch, the first humanist’ The New York Times, http://www.nytimes.com/2004/05/29/style/29iht-conway_ed3__0.html [accessed: 14/02/2015 01:05].

[4] W. R. Estep, Renaissance and Reformation (Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1986) p.20.

[5] J. Zimmermann, Incarnational Humanism: A Philosophy of Culture for the Church in the World (Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 2012) p.118.

[6] J. McConica, ‘Erasmus Disiderius, c.1467-1536’ in H. G. Matthew and B. Harrison (eds) Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

[7] E. Asprem, ‘Positivism and the Religion of Humanity’ Heterodoxology, http://heterodoxology.com/2010/03/08/positivism-and-the-religion-of-humanity/ [accessed: 14/02/2015 01:35].

[8] H. B. Acton, ‘Comte’s Positivism and the Science of Society’ Philosophy, Vol.26, No.99 (1951) pp.291-310.

[9] Bullock, The Humanist Tradition in the West, p.133.

[10] J. Vanheste, Guardians of the Humanist Legacy: T. S. Eliot’s Criterion Network and its relevance to our Postmodern World (Leiden: Brill, 2007). p.3.

[11] J. Huxley (ed)The Humanist Frame (New York: George Allen and Unwin, 1961) pp.11-49.

[12] E. Fromm (ed) Socialist Humanism: An International Symposium (New York: Anchor Books, 1966) p.vii.

[13] H. J. Blackham, Humanism (Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1968) pp.22-23.

On February 27th, 2015, there began a worldwide debate about the colour of a dress. A picture of

On February 27th, 2015, there began a worldwide debate about the colour of a dress. A picture of