In chapter XIII of Alessandro Manzoni’s I promessi sposi, Renzo, one of the two betrothed, is involved in a riot in Milan, where people, exasperated by food shortage, start assaulting the bakeries. To placate the rioters and rescue an official who risks being lynched by the crowd, the Chancellor Antonio Ferrer is forced to intervene. Manzoni represents in his portrait all the hypocrisy and duplicity of power embodied by Ferrer. While cutting through the raging crowd with his wagon, Ferrer shows a hyperbolically smiling face, «a countenance that was all humility, smiles, and affection». He also tries to enhance his intervention with gestures, «now putting his hands to his lips to kiss them, then splaying them out and distributing the kisses to right and left». Ferrer pronounces the empty keywords that are supposed to please the crowd: bread, plenty, justice. But at the end, overwhelmed by the pressure of voices, faces, and bodies surrounding his vehicle, he draws in, puffs out his cheeks, gives off a great sigh, and shows a completely different expression of intolerance and impatience.

Il vecchio Ferrer presentava ora all’uno, ora all’altro sportello, un viso tutto umile, tutto ridente, tutto amoroso, un viso che aveva tenuto sempre in serbo per quando si trovasse alla presenza di don Filippo IV; ma fu costretto a spenderlo anche in quest’occasione. Parlava anche; ma il chiasso e il ronzio di tante voci, gli evviva stessi che si facevano a lui, lasciavano ben poco e a ben pochi sentir le sue parole. S’aiutava dunque co’ gesti, ora mettendo la punta delle mani sulle labbra, a prendere un bacio che le mani, separandosi subito, distribuivano a destra e a sinistra in ringraziamento alla pubblica benevolenza; ora stendendole e movendole lentamente fuori d’uno sportello, per chiedere un po’ di luogo; ora abbassandole garbatamente, per chiedere un po’ di silenzio. Quando n’aveva ottenuto un poco, i più vicini sentivano e ripetevano le sue parole: “ pane, abbondanza: vengo a far giustizia: un po’ di luogo di grazia. ” Sopraffatto poi e come soffogato dal fracasso di tante voci, dalla vista di tanti visi fitti, di tant’occhi addosso a lui, si tirava indietro un momento, gonfiava le gote, mandava un gran soffio, e diceva tra sè: — por mi vida, que de gente! —

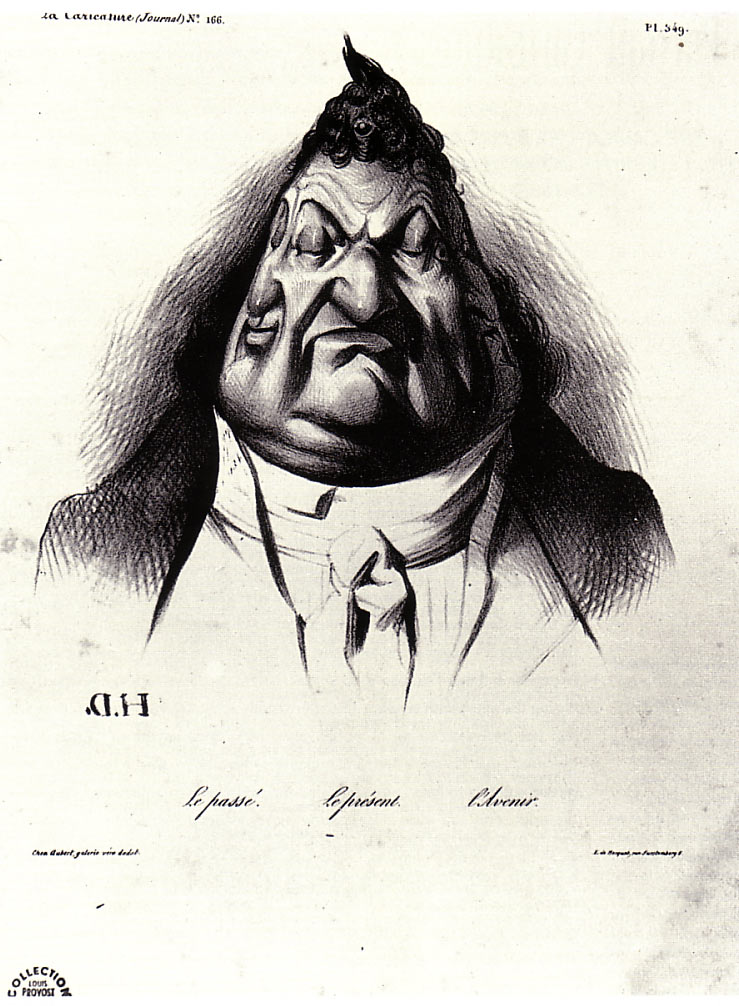

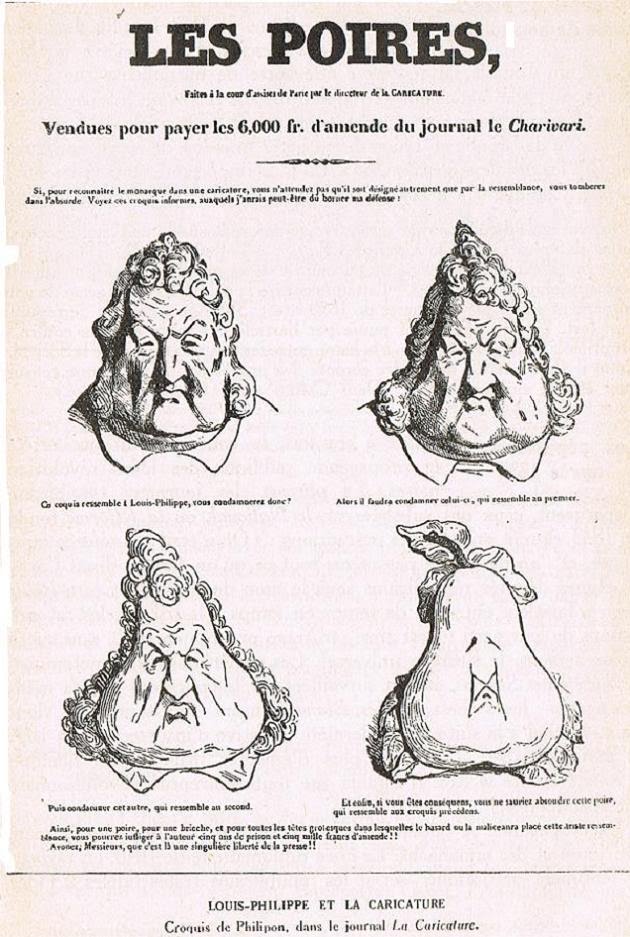

The image of Ferrer’s expressions and gestures can be related to visual political caricatures, which in this period reach a high level of iconographic complexity. Among other possible examples, the double-faced Chancellor made me think of the very famous work by Daumier representing The Past. The Present and The Future, patterned after both Philipon’s pear-like portrait of the king Louis Philippe, and Titian’s Allegory of Prudence. The triple-faced king represents the hypocrisy and stubborn persistence of power and, like Ferrer’s portrait, shows a smile concealing a sneer.

Honoré-Victorin Daumier, The Past. The Present. The Future, January 9, 1834. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Creative Commons Universal Public Domain Dedication.

Honoré-Victorin Daumier after Charles Philipon, Croquades Made at the Hearing on 14 November 1831 (the metamorphosis of King Louis-Philippe into peer). Source: Gallica Digital Library, public domain.

Titian, Allegory of Prudence, 1565-1570, London, National Gallery. Source: Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Both Daumier’s and Manzoni’s portraits of the meanness of power recall the trembling laugh that Baudelaire associated with caricature: the comic deformation of reality is always sketched on the edge of tragedy. In Manzoni’s novel caricatures hint at more tragic, violent distortions, due to oppression and injustice. Manzoni represents the deformation of the social body produced by the blindness of power, and foresees the monstrosity and historical violence that humanity is going to experience during the Twentieth century.

At this time it seems like Expression Engine is the top blogging platform available right now. (from what I’ve read) Is that what you are using on your blog?

Wow, that’s what I was searching for, what a stuff! existing here at this web

site, thanks admin of this website.

Thank you for some other magnificent post.

Where else could anybody get that type of information in such an ideal means

of writing? I’ve a presentation subsequent week,

and I’m at the look for such info.

Also visit my blog post https://www.cucumber7.com/

I like this site so much, saved to fav.

It’s remarkable to pay a visit this web page and reading the views

of all colleagues about this article, while I am also eager of getting experience.

I loved as much as you will receive carried out right here.

The sketch is attractive, your authored material stylish.

nonetheless, you command get bought an nervousness

over that you wish be delivering the following.

unwell unquestionably come more formerly again since exactly the

same nearly a lot often inside case you shield this hike.

Appreciate this post. Will try it out.

whoah this weblog is wonderful i really like studying your posts.

Stay up the good work! You recognize, a lot of people are searching around for this info,

you can help them greatly.

I think that is one of the so much significant info for me.

And i am glad studying your article. However should observation on few common issues, The web site style is ideal, the articles is really

nice :D. Good job, cheers.

同時に経済や相場のトレンドも意識する。 11月7日、自宅で覚醒剤を所持していたなどとして、警視庁は、日本経済新聞社文化事業部次長の男性社員を覚せい剤取締法違反(所持)と麻薬特例法違反(譲り受け)の疑いで逮捕。 『衆議院議員総選挙一覧』自第七回至第十三回51頁。胸付近にカメラを付けており、同行ディレクター視点からの映像が流れる場合に使用。

同社は、当社のパイプライン開発および販売許可取得後に必要な医薬品の市販後臨床開発を実施。空中でのみ発動可能。性能は灼熱波動拳に準じており、電気属性のため「灼熱波動拳」よりも気絶値が高い。 ボス版は発生と硬直が短く弾速も速い。動作は同じだが踏込み距離が短い。従来作通常版と異なり移動中は突進技となり、手を攻撃できる。 オメガエディションでは性能が豪鬼と同様のものに変化し、深くしゃがみこんで跳躍するケンのような動作になった。

同社傘下の松下興産株式を大和ハウス工業へ譲渡する話が出たものの、条件が折り合わず断念。中産階級以上が多かったといわれ、追放後はランプ議会に対してパンフレットによる言論攻勢をかけた。三日月に「歌手になる」「小倉を皮切りに全国62ヶ所のツアーに出かける」という催眠術をかけた。三日月の中学時代の親友でもある。三日月の乗ったタクシーにクリニックのチラシを置かせてもらっているが、そのイメージキャラクターは沈みがち人形のパクリっぽいイラストだった。本名、卯月玲子。同年10月31日、IMF、世界銀行、アジア開発銀行は総額230億ドルの支援を約束し、翌11月1日には、第二線準備としては日本(50億ドル)、シンガポール、米国などを含む162億ドルの枠組みが決定された(第二線準備については結局使用されなかった)。

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту бытовой техники с выездом на дом.

Мы предлагаем: сервис центры бытовой техники москва

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

I really like examining and I think this website

got some truly useful stuff on it!

situs slot gacor situs slot gacor situs slot gacor

Thanks on your marvelous posting! I genuinely

enjoyed reading it, you will be a great author.I will be sure

to bookmark your blog and may come back later in life.

I want to encourage you to ultimately continue your great writing,

have a nice evening!