I publish here the talk I’ve given at the Mis-Shapings conference last September 13 at Queen Mary University.

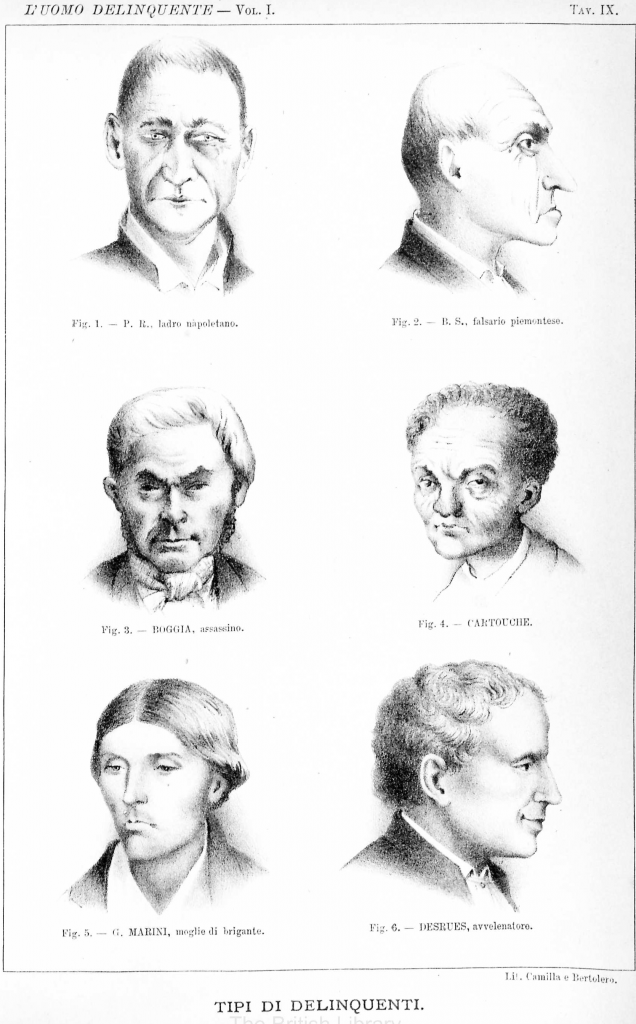

Do we believe in physiognomy? Do we believe, as the Italian anthropologist Cesare Lombroso did, that psychological, emotional, moral attitudes of the individuals can be divined by observing the shape and features of the face?

No, of course we don’t. Physiognomy is pseudo-science, dismissed knowledge, superstition. We can’t make assumptions merely relying on appearances. Can we?

Actually, we do. We do it in our daily life, often unintentionally. But even when we look at artworks we allow us to believe in physiognomy. Continue reading