In 1763 the Abbot Giuseppe Parini composes the poem Il Giorno, a satirical text addressing the inactive, lazy, superficial life of the aristocracy. Pretending to be an ode written in praise and for the education of a Young Gentleman, the poem harshly criticises the parasitic emptiness of noblemen and women. As a parody of a eulogy, Il Giorno deforms the classical poetic style, applying the language and rhetoric of epic and mythological tradition to the frivolous daily activities of the gentleman. The text provides a series of caricatures: first, the Young Lord is scared to death by the word “work”, and his hair stands on end (vv. 54-56):

Ma che? Tu inorridisci, e mostri in capo,

qual istrice pungente, irti i capegli

al suon di mie parole?

Then the text goes on describing the endless series of operations needed for the image of the lord to be restored, with the intervention of an «architect» who is in charge of building his hairstyle. It’s worth noticing that exaggerated hairdressing is a common, recurring target of the Eighteenth-century European social satire and caricature.

William Hogarth, The Five Orders of Perriwigs as They Were Worn at the Late Coronation, Measured Architectonically, November 1761. Source: Wikimedia Commons, public domain

Probably after Samuel Hieronymus Grimm, What! Is This My Son Tom?, June 1774. Source: Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

During this delicate operation, something can always go wrong: suddenly the Lord enrages, is upset, shouts against the hairstylist, crashes his tools, turns everything upside down because him, the hairstylist, is not properly following the French fashion (vv. 514-543):

Lunga fia l’opra tua; né al termin giunta

Prima sarà, che da piú strani eventi

Turbisi e tronchi a la tua impresa il filo.

Fisa i lumi allo speglio, e vedrai quivi

Non di rado il Signor morder le labbra

Impazïente, ed arrossir nel viso.

Sovente ancor, se artificiosa meno

Fia la tua destra, del convulso piede

Udrai lo scalpitar breve e frequente,

Non senza un tronco articolar di voce

Che condanni e minacci. Anco t’aspetta

Veder talvolta il mio Signor gentile

Furïando agitarsi, e destra e manca

Porsi nel crine; e scompigliar con l’ugna

Lo studio di molt’ore in un momento.

Che piú? Se per tuo male un dí vaghezza

D’accordar ti prendesse al suo sembiante

L’edificio del capo, ed oblïassi

Di prender legge da colui che giunse

Pur ier di Francia, ahi quale atroce folgore,

Meschino! allor ti pendería sul capo?

Ché il tuo Signor vedresti ergers’in piedi;

E versando per gli occhi ira e dispetto,

Mille strazi imprecarti; e scender fino

Ad usurpar le infami voci al vulgo

Per farti onta maggiore; e di bastone

Il tergo minacciarti; e vïolento

Rovesciare ogni cosa, al suol spargendo

Rotti cristalli e calamistri e vasi

E pettini ad un tempo.

Thomas Rowlandson, Six Stages of Mending a Face, Dedicated with Respect to the Right Hon.ble Lady Archer, May 29, 1792. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Creative Commons Universal Public Domain Dedication.

Once the toilette is accomplished, a painter goes on to portray the Young Lord. Yet, the portrait immediately turns into a caricature: the Lord’s figure is inflexible and full of faults, the face is too dark, the lips too full and the mouth unrestrained, the nose is flattened, the agile limbs and the noble chest don’t seem that agile and noble. The misshaping of the figure is attributed to the mistakes of the painter, to his lack of expertise, but we can suspect that the accidental caricature is not accidental at all.

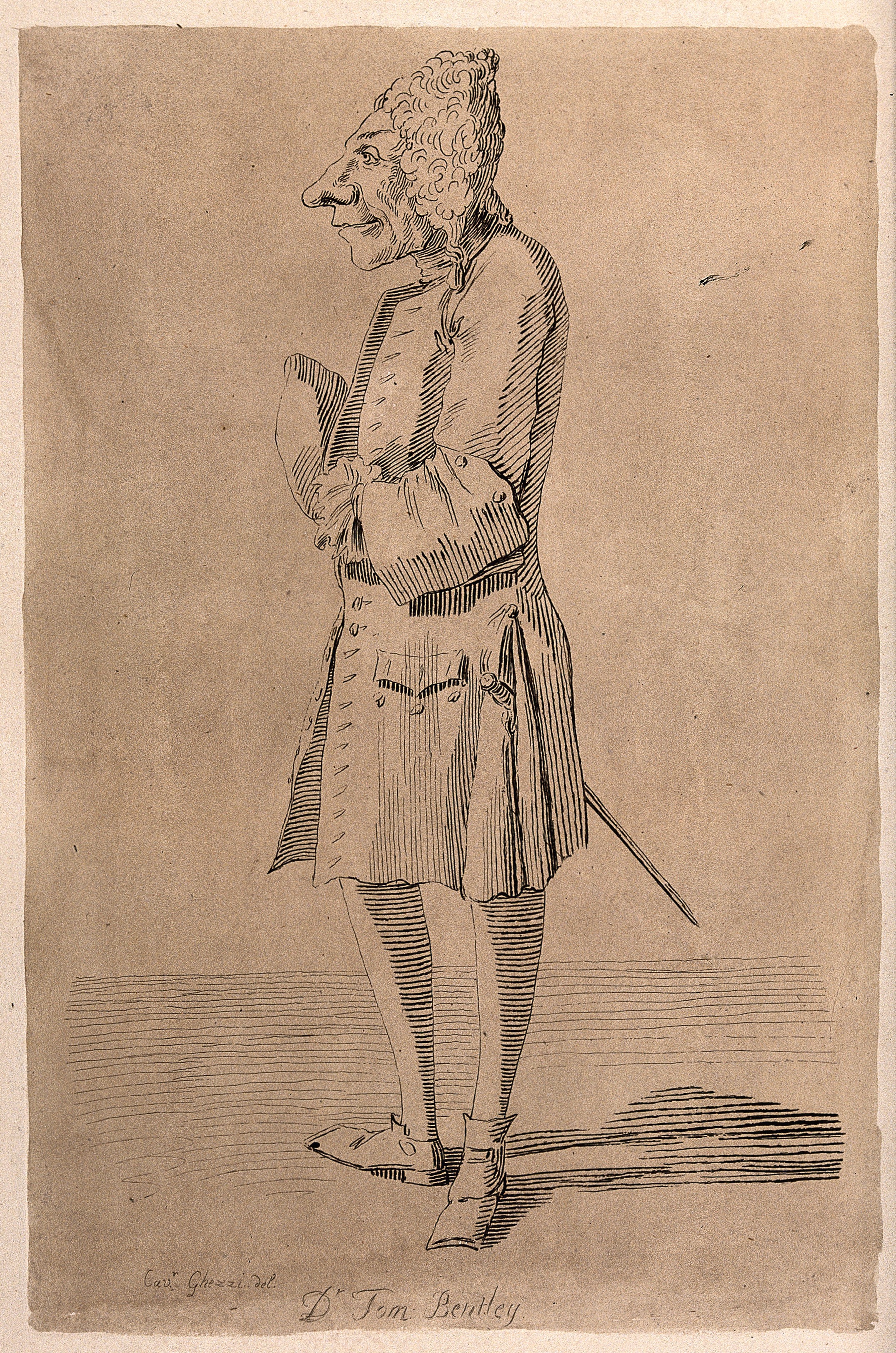

This misshapen portrait can be compared to the caricatures of Pier Leone Ghezzi, who is considered among the first professional practitioners of modern caricature.

Dr. Thomas Bentley wearing a wig and a sword. Etching by A. Pond after Pier Leone Ghezzi. Source: Wellcome Images, public domain.

Both Ghezzi’s and Parini’s caricatures explicitly satirise the official portrait as a genre, which was a powerful device of self-fashioning for the ancien régime ruling class, but also the battlefield where the deconstruction of that class begun. Jurij Lotman highlights Goya’s portrait of the Spanish royal family as an example of the ambiguity between celebration and caricature: a slight deformation of the individuals denounces the degeneration of their power.

Francisco Goya, Charles IV of Spain and His Family, 1800, detail. Source: Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Francisco Goya, Charles IV of Spain and His Family, 1800, detail. Source: Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

As much as Parini’s satirical portrait, Goya’s work is a symptom of the disruption of a whole regime of viewing.

I loved your recipe for vegan chocolate cake! It turned out delicious and was a hit with my family. Discover more fantastic recipes on [Asian Drama](https://asiandrama.live)!