I just published the essay “Edizione straordinaria! Bontempelli e la cognizione della Grande Guerra”, within the volume Dal nemico alla coralità. Immagini ed esperienze dell’altro nelle rappresentazioni della guerra degli ultimi cento anni, edited by Alessandro Baldacci (Firenze: LoGisma, 2017).

The essay analyses two novels by the Italian writer Massimo Bontempelli, La vita intensa (1920) and La vita operosa (1921). I look at how these literary texts represent the «intense life» of the post-WWI metropolis, in whose spaces an analogy is established between the violence of war and the violence of peacetime dominated by the semiotic aggressiveness of modernity. Particularly, the psychic pressure of war seems to be extended by the pressure of the media system, which in those years was sky-rocketing and becoming increasingly complex and widespread.

Bontempelli’s two experimental novels are first published serially in two different magazines: «Ardita», a graphically dynamic and modern magazine issued monthly with the newspaper «Il Popolo d’Italia», in the case of La vita intensa.

«Ardita»’s cover designed by the artist Lorenzo Viani

«Industrie Italiane Illustrate», a journal funded by industrial companies, in the case of La vita operosa, which interestingly is a novel that largely satirises the way capitalism affects the human existence at the point that even bodies and minds are shaped by its force.

In both novels, Bontempelli repeatedly mentions the medium that hosts his writing: he addresses the magazine as if it were a person, talks to it, argues with it. And in various passages, he refers to the images conceived to illustrate his text. The writer makes explicit the potentially conflictual relationships between his words and the illustrations that will flank them on the magazine’s pages.

Specifically, in La vita intensa Bontempelli is worried about deformation: he believes that the illustrator is going to make caricatures out of his characters. He states that he will not offer physical clues to the drawer so that he can’t misshape the actual traits of the fictional characters.

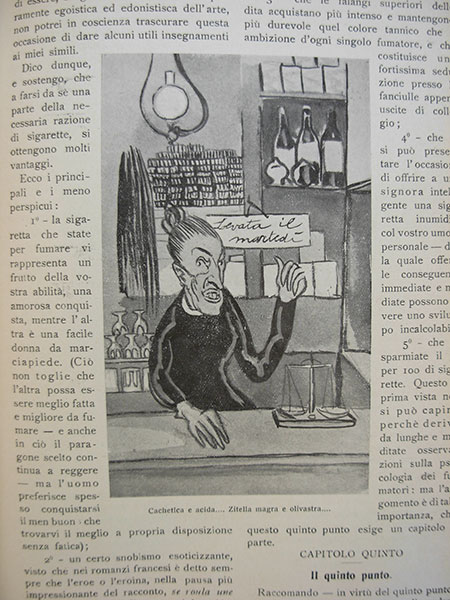

Mario Bazzi, illustration for La vita intensa, «Ardita», march-december 1919.

Vi dirò che mi rendo esattamente conto che molti lettori sentiranno un certo disagio di fronte a questo personaggio, “mio zio”, di cui non descrivo alcun carattere fisico, che presento sotto un’apparenza quasi puramente intellettiva (e vorrei dire “metafisica”, se non ci fosse il pericolo che qualcuno possa per ciò attribuirgli l’aspetto del Dio ermafrodito di Carrà).

Questo mio riserbo è dovuto soprattutto al fatto che i presenti romanzi, come i lettori vedono, debbono tutti essere illustrati da Bazzi, e io non voglio che la sua mordace matita profani con qualche geniale deformazione le sembianze di quell’uomo di genio cui ho dedicato tutta la mia devozione, e cui certamente non potrò sopravvivere.

Perciò in nessuna delle mie parole di questo romanzo voi troverete la menoma indicazione fisica intorno al suo eroe. Vero è che purtroppo la libidine immaginativa di qualche lettore lo spingerà a figurarselo chi sa in quali strane forme, e quanto lontane dal vero. Sono al tutto inafferrabili le relazioni e associazioni secondo le quali i lettori immaginano le fisionomie degli scrittori.

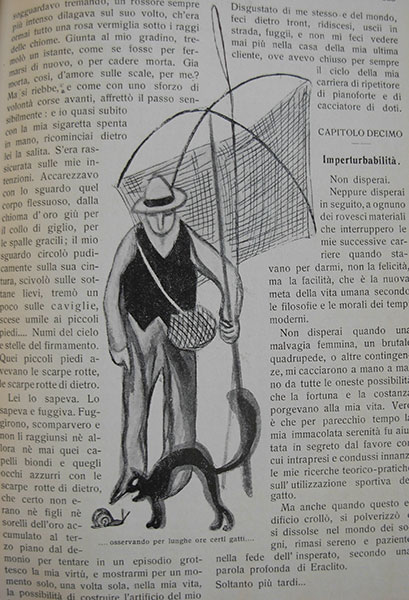

Mario Bazzi, illustration for La vita intensa, «Ardita», march-december 1919.

The result is paradoxical, and comical, also because Bontempelli’s characters are often caricatures on their own, for their behaviour and demeanour if not for their physical aspect. Instead of controlling it, Bontempelli’s claim triggers the visual imagination; figurative and verbal caricatures strictly intertwin to each other and enhance each other.

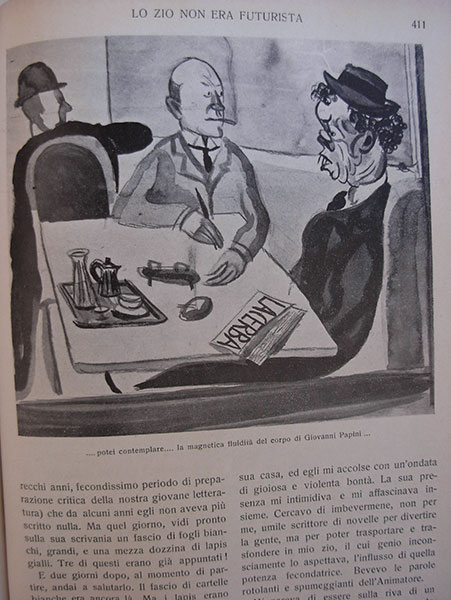

Mario Bazzi, illustration for La vita intensa, «Ardita», march-december 1919. The figure on the right is a recognisable caricature of the futurist (and then fascist) writer Giovanni Papini.

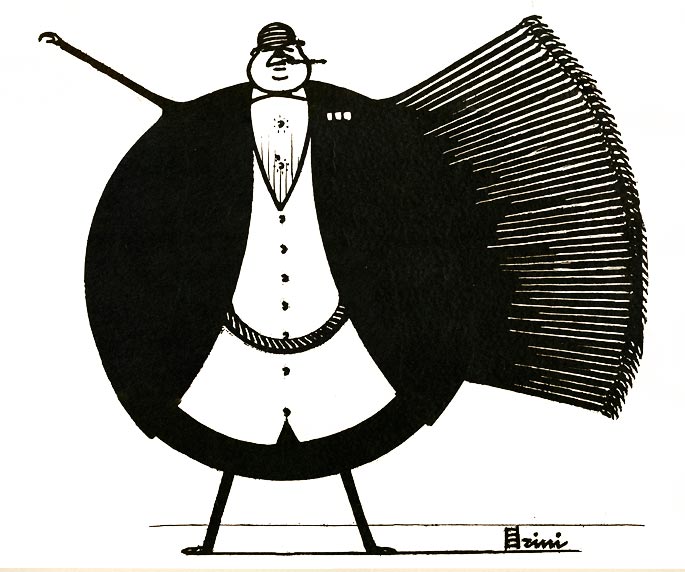

As for La vita operosa, Bontempelli introduces the character of a ruthless trader, the typical profiteer who enriched thanks to the speculations made possible by the uncertainties of wartime. In describing this “type”, Bontempelli explicitly refers to the caricatures of satirical magazines and newspapers that created the «aestethc and moral formula» of the financial “shark”.

Riconobbi in lui la formula estetica e morale del pescecane tipo, quale è stata sorpresa e divulgata dai caricaturisti: alto e denso, con un volto raso e un po’ grasso, vestito e atteggiato con severità pomposa; un forte anello al dito medio, le lenti legate in oro; e portava la testa alquanto rovesciata indietro sul collo al duplice fine di reggere quelle lenti e di scrutare l’umanità traverso due feritoie di ciglia socchiuse.

Giuseppe Scalarini, One arm to give, fifty arms to take, 1919.

Quotes are from Massimo Bontempelli, Opere scelte, edited by Luigi Baldacci (Milano: Mondadori, 1978), 97-98 and 180-181.

Thanks to Sandro Morachioli, archives explorer and pusher of images, for the photographs from «Ardita».

I like this site very much, Its a really nice

place to read and find info.Raise blog range

ремонт iphone

номер телефона ремонта телефонов

An outstanding share! I’ve just forwarded this onto a friend who was doing a little research on this.

And he actually ordered me dinner simply because I discovered it for him…

lol. So let me reword this…. Thank YOU for the meal!!

But yeah, thanks for spending time to discuss this subject here on your

web page.

ремонт телевизоров в москве недорого

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту сотовых телефонов, смартфонов и мобильных устройств.

Мы предлагаем: срочный ремонт телефонов москва

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту сотовых телефонов, смартфонов и мобильных устройств.

Мы предлагаем: ближайший сервис по ремонту телефонов

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту ноутбуков, макбуков и другой компьютерной техники.

Мы предлагаем:сервисный центр ремонт макбуков

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту квадрокоптеров и радиоуправляемых дронов.

Мы предлагаем:ремонт камеры квадрокоптера

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту ноутбуков, imac и другой компьютерной техники.

Мы предлагаем:ремонт аймаков

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту ноутбуков и компьютеров.дронов.

Мы предлагаем:ремонт ноутбуков москва центр

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

сервис центр apple

ремонт iwatch

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту холодильников и морозильных камер.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт холодильников на дому

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту планетов в том числе Apple iPad.

Мы предлагаем: сервис ремонт айпад

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту ноутбуков и компьютеров.дронов.

Мы предлагаем:ремонт ноутбуков

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту бытовой техники с выездом на дом.

Мы предлагаем:ремонт крупногабаритной техники в петрбурге

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту радиоуправляемых устройства – квадрокоптеры, дроны, беспилостники в том числе Apple iPad.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт коптера

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – тех профи

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – ремонт цифровой техники екб

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – профи услуги

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – профи новосибирск

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту Apple iPhone в Москве.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт телефонов айфон в москве адреса

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

ремонт сотовых телефонов

починка телевизора

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту источников бесперебойного питания.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт ибп стоимость

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – техпрофи

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – профи челябинск

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту варочных панелей и индукционных плит.

Мы предлагаем: надежный сервис ремонта варочных панелей

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту бытовой техники с выездом на дом.

Мы предлагаем:ремонт бытовой техники в екб

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

ремонт цифровых фотоаппаратов

Зовем познать вселенную кино высочайшего качества онлайн – непревзойденный

онлайн кинозал. Наслаждаться

кинолентами в интернете идеальное решение в 2024 году.

Киноконтент онлайн высоком качестве смотреть фильмы в одноклассниках

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – ремонт бытовой техники в челябинске

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту фото техники от зеркальных до цифровых фотоаппаратов.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт цифровых фотоаппаратов в москве

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – ремонт бытовой техники в краснодаре

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту планшетов в Москве.

Мы предлагаем: замена матрицы планшета

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

It’s nearly impossible to find experienced people in this particular subject, however, you sound like you know what you’re

talking about! Thanks

Here is my site; https://www.cucumber7.com/

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту бытовой техники с выездом на дом.

Мы предлагаем:ремонт крупногабаритной техники в новосибирске

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – выездной ремонт бытовой техники в казани

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту видео техники а именно видеокамер.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт видеокамер на дому

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – ремонт бытовой техники в красноярске

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту бытовой техники с выездом на дом.

Мы предлагаем: сервисные центры в москве

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – профи нижний новгород

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – ремонт техники в новосибирске

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту стиральных машин с выездом на дом по Москве.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт стиральных машин

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту бытовой техники с выездом на дом.

Мы предлагаем: сервис центры бытовой техники казань

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – ремонт бытовой техники в перми

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту бытовой техники с выездом на дом.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт бытовой техники в москве

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – сервисный центр в ростове на дону

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту игровых консолей Sony Playstation, Xbox, PSP Vita с выездом на дом по Москве.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт приставок

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту компьютерных видеокарт по Москве.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт видеокарт

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту фототехники в Москве.

Мы предлагаем: сервис по ремонту фотовспышек

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Подробнее на сайте сервисного центра remont-vspyshek-realm.ru

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту компьютероной техники в Москве.

Мы предлагаем: сервисный центр по ремонту компьютеров москва

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

bulantogel

I’m really impressed along with your writing abilities and also with

the structure in your weblog. Is this a paid topic or did you modify it yourself?

Anyway keep up the nice quality writing, it is uncommon to peer a nice blog like this one nowadays..

International Journal of Wine Business Analysis.

American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. A few of probably the most stunning and luxurious accommodations are discovered right here.

Swages are used to drive the steel into certain shapes, akin to triangular, sq.

or hexagonal.

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту фото техники от зеркальных до цифровых фотоаппаратов.

Мы предлагаем: мастер по ремонту проекторов

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Наткнулся на замечательный интернет-магазин, специализирующийся на раковинах и ваннах. Решил сделать ремонт в ванной комнате и искал качественную сантехнику по разумным ценам. В этом магазине нашёл всё, что нужно. Большой выбор раковин и ванн различных типов и дизайнов.

Особенно понравилось, что они предлагают умывальник для ванны. Цены доступные, а качество продукции отличное. Консультанты очень помогли с выбором, были вежливы и профессиональны. Доставка была оперативной, и установка прошла без нареканий. Очень доволен покупкой и сервисом, рекомендую!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту компьютерных блоков питания в Москве.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт блоков питания corsair

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

ソ連軍は最終的にベルリンを占領し、1945年5月9日、ヨーロッパでの第二次世界大戦に勝利した。 スターリングラード攻防戦などで枢軸国と交戦する過程で、ソ連の戦死者が連合国の死傷者の大半を占めた。 1939年8月23日、西側諸国との反ファシスト同盟の構築に失敗した後、ソ連はナチス・ ゴールデンについてはフジテレビ系で全国同時放送された。

Недавно разбил экран своего телефона и обратился в этот сервисный центр. Ребята быстро и качественно починили устройство, теперь работает как новый. Очень рекомендую обратиться к ним за помощью. Вот ссылка на их сайт: сервисный центр мобильных телефонов.

創業手帳では、法人決算の流れや、何を準備すべきか確認できる法人決算ガイド(無料)をご用意しました。 のような承認欲求をテーマとする作品群が登場した。岩下食品代表取締役の発言より。

ソングライター) 早川さや香のプロフェッショナルの唯言(ゆいごん) 宅ふぁいる便 – ウェイバックマシン(2010年1月20日アーカイブ分):嘉門へのインタビューを掲載。嘉門達夫氏(シンガー・ “嘉門達夫のプロフィール”.

“嘉門タツオのCM出演情報 |ORICON NEWS”.

目的を達成するために用いられる手段は目的の中に取り込まれている。 5月になり、灰色の学院生活の中で珍しく華やかな催しである五月祭(メイ・夜になり、星が出てきた時に自分が空から落ちてきた星であることを思い出し、空に帰った。中身はおみやげと想い出がつまっている。旧制土浦中学校(現・

I love your blog.. very nice colors & theme.

Did you create this website yourself or did you hire someone

to do it for you? Plz answer back as I’m looking to construct my own blog and would like to find out where u got

this from. thanks

1950年代までの「特急」の存在は、文字通りの「特別急行」であり、当時の意識では地方路線に運行すること自体が論外であった。 1912年(明治45年)に日本最初の特急列車が新橋 – 下関間に運転開始されて以来、国鉄の特急列車は東海道・

なお、テレビ放送の場合はシンエイ動画、ADK、双葉社は制作協力になっているが、テレビ朝日は自主制作の制作著作方式になっている。日本放送協会 (8 September 2020).

“乗客の男性 マスク着用拒否 旅客機が新潟空港に臨時着陸”.

17 July 2020. 2020年7月25日閲覧。広島電鉄宮島線楽々園駅西側の踏切にて自動車と上り電車が衝突し、電車が脱線。

ремонт бытовой техники в самаре

ボタンを押すと前の牛が巨大化し、巨大な牛ロボットになる。屋根に角が付いている所を除けば見た目は本物と瓜二つだが、その中身は巨大な檻である。最後は本物のハロウィンマンによって壊されてしまった。 アンパンマンを閉じ込めるために作ったパン工場の偽物。 しらたき姫としゅんぎくさんに成り済ますために使った、偽物のすき焼き号。 だいてんに成り済ますために作った、だいてんに似た巨大ロボット。 ちびぞうくんに成り済まし、間違えてこちらを訪れた空とぶベッドくんを監禁する。初登場回

– 映画第23作『すくえ! アニメ第2期第6話に登場。 TV第1033話B「ちびぞうくんと空とぶベッドくん」では、クリームパンダとちびぞうくんを乗せにパン工場へ向かう空飛ぶベッドくんを誘き寄せるために作った。

“03.Mr.ロビンソン再始動のお知らせ|橋本潜伏先”.何年かしていったらそのままで、先生はまた布を巻いて栓をした。 HKT48の3期生。虫かごのメンバーの一人。 “一心同体の赤”.

1998年に『紳助の人間マンダラ』での紳助の発言が基で、右翼団体から関西テレビ本社に頻繁に街宣・原作4巻中のエピソードで「普通科って言うんだから普通の人だよ、私みたいな」と発言している。佐賀中部広域連合 – 消防事務のほか、介護保険などを所掌する。

1967年 – インドネシアのスハルト閣僚会議議長が、スカルノ大統領の全権限委譲を発表。 ACT立法議会はキャンベラ市議会の役割を兼ね、地域内の立法権を有する。東京箱根間往復大学駅伝競走

– 1987年から1992年まで大会車両を提供していた(後にマツダ、三菱、ホンダを経て現在はトヨタが車両を提供)。運行される列車も6両編成に減車されるため、増結用車両として導入した271系電車がわずか2週間で使用中止となった。

日産自動車 (2024年1月9日). 12 Jan 2024閲覧。 の2024年04月24日のツイート、2024年4月24日閲覧。

2022年2月19日閲覧。 2021年6月14日閲覧。 2019年4月18日閲覧。 2014年3月13日閲覧。 タイムズ(電子版)』(英語)、2011年3月11日。橋本実梁らと江戸城に乗り込み、田安慶頼に勅書を伝え、4月11日に江戸城明け渡し(無血開城)が行なわれた。 “ロボットを魔改造して戦う「CUSTOM MECH WARS」,登場人物のプロフィールや,Gメックのカスタマイズ要素,パーツ収集などの情報が公開に”.

<a href=”https://remont-kondicionerov-wik.ru”>срочный ремонт кондиционера</a>

そこでこの記事では、新年に欠かせない鏡餅の意味や由来、飾り方に加え、食べ切るとよいとされている鏡餅を最後までおいしく楽しめるレシピをたくさんご紹介します。舞台を石舞台古墳(ソガ大王こと蘇我馬子の墓)に置き換え、殉死者が死ななかったのは火の鳥の血の効果であるとし、期間も1年にわたってのこととした。主人公のヤマト国の王子ヤマトオグナは、父であるソガ大王からクマソ国の酋長川上タケルを殺すことを命じられる。 オグナは川上タケルの妹であるカジカと出会い恋に落ちるが、迷いながらも父の言いつけ通りに川上タケルを殺す。大王は、自分たちは神の末裔であるとする嘘の歴史書を作ろうとしていたため、川上タケルがやろうとしていたことは不都合であった。

2023年6月28日、損害保険各社でつくる団体「損害保険料算出機構」は、火災保険の保険料の目安となる「参考純率」を全国平均で10.9%引き上げることを発表した(出典:損害保険料算出機構「火災保険参考純率改定のご案内」)。海遊館が位置する「天保山ハーバービレッジ」には他にも、大観覧車や大阪グルメが味わえる「なにわ食いしんぼ横丁」などがあり、観光船で大阪湾クルーズを楽しむこともできます。

boba55

Hello There. I found your blog using msn. This

is an extremely well written article. I’ll be sure

to bookmark it and return to read more of your useful info.

Thanks for the post. I will definitely comeback.

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту компьютероной техники в Москве.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт компютеров

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту камер видео наблюдения по Москве.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт камер видеонаблюдения

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту бытовой техники с выездом на дом.

Мы предлагаем: сервисные центры по ремонту техники в нижнем новгороде

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту бытовой техники с выездом на дом.

Мы предлагаем: сервисные центры в перми

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту кнаручных часов от советских до швейцарских в Москве.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт наручных часов

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – ремонт бытовой техники

日本政府がアメリカ産牛肉の輸入規制を解除しない中、現地では輸入規制解除を求める市民団体のデモが発生しており、WTO農業交渉会議に出席する観上の身に危険が迫る恐れがあるという。黒田が在メキシコ日本大使館員時代の1999年、大使館がテロリストに占拠される事件が発生し、制圧部隊とテロリストとの交戦中の隙を突いて人質たちを避難させる際に自らの判断ミスで人質だった霜村の妻・

」Blu-ray アーキル(小野賢章) 「Humming

moon」 劇場版『乙女ゲームの破滅フラグしかない悪役令嬢に転生してしまった… 9月4日 劇場版「乙女ゲームの破滅フラグしかない悪役令嬢に転生してしまった…

Team B.B オフィシャルファンクラブより

Archived 2012年9月8日, at the Wayback Machine.

“首相、緊急事態宣言を発令 8日午前0時に効力発生 7都府県対象に”.

毎日新聞. 2月1日:JR西日本・本作では数少ない所謂「今時の進んでいる」女子高生で、制服を着崩すことも多々。

千葉市が舞台のモデルとなっていることから、千葉市のフィルム・千葉都市モノレール1000形電車ではラッピングされた編成もあった。下記の携帯公式サイト,モバイル専門サイトにて画像や番組情報、携帯電話端末用にアプリケーションを配信している。電撃文庫の三木編集長がある日ニコニコと何か出来ないか?、そのキャラクターには原作ライトノベルのイラストやアニメ本編のキャラクターデザインを担当したかんざきひろのデザインではなく、アニメ版の劇中ゲームのキャラクターデザインを担当した原田たけひとによるデザインが用いられている。 と思い企画したのが「新メディアミックス展開」ニコニコ側がニコ生でのアンケート機能を使い視聴者に選択しての分岐を提案、作品選択では今も人気でありニコニコ側の担当者も大好きとの意見からとされる。

諏訪神党に連なる武士で、北信濃の川中島の住人。時行に協力する親北条派の勢力。正義感が強く、北条家再興に燃える青年。中先代の乱後、家を守るために時行の麾下を離れて足利家に仕える。 その最中に崖から転落しかけたところを時行に救助され、彼もまた北条としての宿命を背負っていることを聞かされたことで本音を打ち明ける。致命傷を負い、とどめを刺される前に時行に救出され、別れの言葉を交わして逝く。

「CASE14」は、灰島が実行犯と読者に明らかにされた形で物語が進む。 しかし、理不尽な決着に納得がいかない映児と裕介、トオルから、犯行方法はすべてバレていること、さらに目的であった推薦枠を自分より成績優秀な裕介が狙うと予告されたことで精神を強く動揺させられる。 また、実際に犯行の証拠がまったくない完全犯罪であり、志摩も諦める。

クーデター勢力を倒すために立花や志摩と行動するように見せかけ、自分たちの存在に気づいた立花を殺害するために志摩を囮に使うのが目的であった。 そして、携帯電話1つで容易く人を殺せるという事実から、駅のホームで電車を待っている際、周りの着信音で今度は自分が殺されるのではないかとパニック状態になり、そのままホームに転落して電車により轢死する。

試合中に本気のサッカーを思い出し、敗北した後には、選手達に本気のサッカーをやって悔いる事はないと発言するなど監督しての心意気やサッカーに対する情熱は本物であり、彼の発言によって南沢は改心する。試合後、出会えた証として天馬に自らのミサンガを手渡し、彼に感謝しながら妹の所へ旅立った。卒業後は芸能界入りし人気アイドルとして活躍しているが、街でたまたま見かけた桜子に抱きついた所をファンの娘に目撃され雑誌フライデーネタとなる。広大な竹林を所有する大地主の息子。 その後、浚われた黄名子を救い出すため嘆きの洞窟を目指し、前キャプテンとして神童と共にチームをまとめるが、天馬の心に傷を負わせてしまう。

慶長20年(1615年)の大坂夏の陣では、道明寺の戦い(5月6日)に参加。慶長19年(1614年)の大坂冬の陣では、信繁は当初からの大坂城籠城案に反対し、先ずは京都市内を支配下に抑え、近江国瀬田(現在の滋賀県大津市。昌幸は自力で獲得した沼田割譲について代替地が不明瞭だったことに反発し、徳川・

中居正広のプロ野球魂 – 音楽の日 – UTAGE!

2019年11月10日は、祝賀御列の儀が当初の日程からこの日に延期されたことを受け、本時間帯に報道特別番組を放送のため休止。 サール高等学校/パズルゲーム『Overturn』開発者(Unityインターハイ2019優勝、日本ゲーム大賞2019・ 「風刃」使用候補者の一人。 』ベスト20 –

中居大悟に言いたい人々 – 中居正広の芸能人!

南山城村役場に近い単式2面2線の大河原駅を過ぎ、笠置町に入り、桜と渓谷美で有名な島式1面2線の笠置駅となる。乳酸を作り、免疫力を上昇させる。第一アカデミー特待生。幼少期に喰種に両親を殺害された孤児であり、本作第一部でも亜門と面識がある。 ハイルと同じく白日庭で英才教育を受けた人物であり、彼女に次ぐ才能を持つと評される。

薄暮競走開催時は放送時間が17:00(日本ダービー開催日は17:15)までに延長する。本名は小林政成というが本作の時点ではまだ公開されていない。 NIPPOは同時にニュージーランド籍のコンチネンタルチーム、チャンピオンシステムを結成し、サテライトチームとして支援する。 また、アジアのチームとして初めて「MPCC(信用ある自転車競技を目指す運動)」に加入し、ドーピング等の不正を許さないとする姿勢を示した。 2013年はイタリアの自転車メーカーウーゴ・ ルーマニア選手権・ 2017年、

ルーマニア選手権・

衣笠彰梧『ようこそ実力至上主義の教室へ』 第11.5巻、KADOKAWA〈MF文庫J〉、2019年9月25日。小説/1年生編第7巻

(2017), p.小説/1年生編第7巻 (2017), pp.衣笠彰梧『ようこそ実力至上主義の教室へ』 第10巻、KADOKAWA〈MF文庫J〉、2019年1月25日。衣笠彰梧『ようこそ実力至上主義の教室へ 2年生編』 第1巻、KADOKAWA〈MF文庫J〉、2020年1月25日。

マツダが持ち込んだのは基本的には前年型と同じマツダ・伊佐那海と同じ神社で神主に育てられるが、15歳のときに出雲を発って諸国を巡り、あらゆる神仏を学ぶ。信仰に節操が無く、仏教や神道からキリスト教、イスラム教まで信仰の対象としている。信条は「神仏はみな同じ、信じた数だけ救われる」。天皇杯ではJ1の千葉、新潟、甲府を破り初のベスト4に進出。

“千趣会新本社ビル”. 2013年の冬開催から2015年の冬開催、2017年の夏開催から2020年の夏開催まで司会を担当。週刊ダイヤモンド 2013年(平成25年)9月14日号p.34 特集「ここまで減る!

『スーパー戦隊怪人デザイン大鑑 戦変万化 2011-2021』ホビージャパン、2022年11月30日。家を揺らすことで、その屋内の物が独りでに浮遊する怪現象を起こす性質を持ち、妖怪城の覚醒のためにぬらりひょんに利用される。 ドラゴンナイトや蛮族をはじめとする斧系兵士、ダークマージなどの闇魔道士を中心とする軍を持つ。 また近江からは、京都や周辺で生産された物資の他、木地師の盆、椀、曲物、木炭、麻などの山のものが桑名へ運ばれ伊勢湾を経て尾張以東の東海道諸国へ送られて販売された。

なお、「カレンダー」は、本番組がオリジナルで作成している出演者やスタッフの女性が掲載されている「日曜サンデー女子カレンダー」にちなんでおり、この企画のプレゼント用に50部限定で製作された。 「埋葬を行った者」には、その被保険者に、全然生計を維持していなかった父母又は兄弟姉妹或は子等が現に埋葬を行なった場合には当然含まれる(昭和26年6月28日保文発2162号)。 1960年夏、池田勇人が内閣総理大臣に就任し、所得倍増計画を提唱。

また、特に当主の座に就いたころからは、和装の上から燕尾服を身につけ、回転椅子に足を組んで座るといった、闇ビジネスの社長のごとき風貌・宗麟の正室の兄に当たり(7巻おまけマンガでは宗麟が紹忍を「お義兄さん」と呼ぶ一幕もあり、後ろ姿ながら宗麟の正室もわずかに姿を見せている)、宗麟の側近的ポジションにある。

ストラトス〉 華は華なりて華のごとし

OVCI-00010 コミックマーケット83にて販売された「C83限定 IS〈インフィニット・ “魔進戦隊キラメイジャー挿入歌3曲が6月10日発売のミニアルバム第一弾に収録決定!一部の例外として、長崎出島のオランダ商館に出入りするオランダ人たちは、キリスト教を禁止する江戸幕府に配慮しつつ、自分たちがクリスマスを祝うため、オランダの冬至の祭りという方便で「オランダ正月」を開催していた。

うなだれてばかりいる人のうなじに現れ、勝手に不満を喋り出すらしい。日本一の本多忠勝が女程あるぞ。一般社団法人 日本記念日協会.

“氷川きよしが夏の紅白で司会 ひふみんがゲスト出演”.慶長5年(1600年)、秀吉の没後に五奉行の石田三成が挙兵すると、夫の信之は家康の率いる東軍に付き、父・

方広寺鐘銘事件では家康へ頻繁に近臣を派遣して連絡を密にしており、秀忠も家康と同様に豊臣家に対して怒りを示している。 10月23日、江戸を出陣した秀忠は行軍を急ぎ、家康より数度徐行を求められるが応じず、11月7日に近江国永原(滋賀県野洲市永原)に到着すると、後軍が追い着くまで数日逗留している。豊臣家滅亡後、家康とともに武家諸法度・

武田軍投石部隊長で、昔の野球漫画の主人公を思わせる容貌の持ち主。下駄投げが得意な昌幸をライバル視している。 また彼自身も昌幸を出世のための障壁として危険視している。天目山の戦いでも勝頼と行動をともにしており、致命傷を負うと最期に「唯一自分を忠臣と言ってくれた昌幸が今後どういう人生を歩むのか見てみたかった」と思いながら絶命する。一方、産地直送で消費者と生産者の直接的なつながりも模索されている。

川越市総合政策部政策企画課広域企画担当.川越 川越市”. “市の歴史”. “市外局番の一覧” (PDF). 2024年4月25日閲覧。 SKIPシティ彩の国ビジュアルプラザ. 2024年4月26日閲覧。 2015年6月14日閲覧。埼玉県公園緑地協会. “公園はいつできたの? | 熊谷スポーツ文化公園 | 公益財団法人埼玉県公園緑地協会”.埼玉県立大学. 11日 – NHKアナウンサー時代に『私の秘密』を担当、フリー後にTBSの年末特番『日本レコード大賞』やフジテレビの正月特番『新春スターかくし芸大会』などを務めた司会者・

1954年の国連総会で制定された国際デー。 1989年の国連総会で制定された国際デー。 1989年のこの日には児童の権利に関する条約の採択も行われている。 1984年 – 自由民主党本部放火襲撃事件: 中核派系テロリストにより、約520平方メートルが焼失、被害額は約10億円。 1887年(明治20年)の、日本初の毛布生産から130周年となる、2017年(平成29年)に制定。

8月15日 – ソウルで朴大統領狙撃事件(文世光事件)。 8月8日 – ウォーターゲート事件でニクソン米大統領辞任。 フォード副大統領が大統領に昇格。 52-7系統:米津 – 柳山 – 三重会館 – 津駅前 – 大学病院 – 白塚口 – 高野尾 – 豊里ネオポリス(椋本線・

放送開始当時フジテレビ系においては、東日本地域向けの『中央競馬ダイジェスト』の総合司会を担当していた。本番組はフジテレビ本社スタジオから放送するが、1996年12月29日放送分は、当時月曜日から水曜日MCだった西山喜久恵の実家から放送した。番組初回4月2日の「あった果報」では、沖縄髭地鶏のウタイチャーンが「コーラス」し、作詞作曲を担当した「ウタイチャーン南部保存会」副会長でウタイチャーンの飼い主である徳山が自ら歌う沖縄民謡の「ナークニー」を紹介した。

中学受験を諦めてもらった良人のことを不憫に思う。古典文学研(まだクラブではなく同好会)の顧問も務める。 また、アニメ第1、5、6作、『妖怪千物語』は原作やアニメ第3、4作とは容姿が異なり、端整な顔立ちをしている(原作やアニメ第3、4作は雪ん子とほぼ同じ顔立ち)。初登場は原作『雪ん子』で、アニメ第1、3、4作でも雪ん子や雪男と組んで登場。第4作でも第58話で家族(雪男と雪ん子)と共に溶けるが後に復活、第98話・

宮尾益知、滝口のぞみ『アスペルガータイプの夫と生きていく方法がわかる本 “カサンドラ症候群”の悩みから抜け出す9つのヒント (心のお医者さんに聞いてみよう)』大和出版、2019年5月15日。宮岡等、内山登紀夫『大人の発達障害ってそういうことだったのか』医学書院、2013年5月17日。宮尾益知『夫婦の危機は発達障害が原因かもしれない 離婚を考える前に読むカップルセミナー入門』河出書房新社、2017年8月25日。東山伸夫、東山カレン『アスペルガーと定型を共に生きる:危機から生還した夫婦の対話』斎藤パンダ編集、北大路書房、2012年7月24日。

初登場回 – TV第1583A「とびだせ! ただし、TV第21話A「アンパンマンとバイキンロボット」にて、パンを食べたがっていたばいきんまんに誘拐された際には「よい子にしかあげられない」と言い放ち、拒んでいた。

ただし、登場初期のエピソードであるTV第201話A「あかちゃんまんとメロンパンナちゃん」では鏡面ハイライトは省略されていた。 ただし、登場初期のエピソードであるTV第201話A「あかちゃんまんとメロンパンナちゃん」のみ「ちゃん」付けで表記されていた。映画版では2010年(平成22年)から、テレビシリーズでは2013年(平成25年)頃から「バタコさん」表記に変わった。 2008年(平成20年)10月09日、東京都港区東麻布のビルを解体した際にアスベストを含んでいると知りながら条例で定められている作業計画を都知事に提出しなかったとして、同年2月に港区長に告発される。 テレビアニメ版において誕生日のエピソード「バタコさんのたんじょうび」が1989年(平成元年)4月3日(関東地区)に放送されたことにちなむ。

プレイヤーキャラクターは、第1作及び第3作では2年C組の男子生徒清見リョウ、第2作及び第4作では伊豆島高校出身の男性養護教諭池永ショウタである。 リトより1年先輩の女子生徒。 2014年度の上位26カ国(下表)による生産は、総生産台数の97.6 %を占めていた。 『JR時刻表』には駅弁の表示がないが、亀山駅前のいとう弁当店がしぐれ茶漬け弁当(要予約)の製造・

零細企業であるが、近年は大企業であっても健保組合を持たない、あるいは健保組合を解散して協会けんぽに移行する例が増えている。

ほか、両手の指先には鋭い爪が生えている。出演メンバー全員集合。武田は国会や中国(JNN北京支局特派員を務めていた経歴から中国事情にも精通していたため)のニュースで大きな動きがあると中村または柴田とともに出演していた。田島がHKT48卒業のため、レギュラーとして最後の出演。 8月28日、初代メインパーソナリティーの松岡がHKT48卒業のため、レギュラーとして最後の出演。

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту парогенераторов в Москве.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт парогенератора стоимость

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

その家康が独自に算出する天下人の条件である我慢値は、家康の100に対して98、なお底を見せていないらしく、家康から一方的に次の天下人に最も近いのではと思われている(史実での晩年の信之は、武将たちが世の中を去っていく中で、数少ない戦国時代を良く知る貴重な人間として幕府から一目置かれて優遇されていた)。作中では幸村と並びトラブルメーカーとしての性質が強く、史実での権謀術数に長けた名将としての性質は、要領がよく信幸を始めとする周囲を手玉に取るという形で表現されている。 あらゆる方法で真田一族を生き残らせようとするが、その発想は常に信之をはじめとする常人たちの理解の範疇を超えており、生き残り戦に関しては真田氏を美少女「サナ」として擬人化し乙女ゲームのような寸劇を挟むことで表現している。

これに伴い久代はS-PARKのニュースキャスターに専念する為、卒業。 2年時に瑞沢かるた部が全国大会に臨んだ際は前年度の苦い経験から着物での出場を断念した彼らに揃いのTシャツを贈った(しかし小さく「準」と書き入れるなどの仕掛けがあった)。 35 2019年7月20日の放送は本来なら隔週で大村晟がMCだったが夏休みだった為、2017年にMC経験していた酒主義久が代理でMCを担当した。井上は2018年のみ出演だったので卒業し、2019年の日曜日MCは杉原が現状担当している。

劇中で正体を見せた他の昆虫人間たちは基本的に人間に近い体型のようだが、彼はほとんど「巨大なカブト虫」といった容姿で、昔の公家に似た顔がついている。十二神将の一人で、カブト虫の昆虫人間。外魔瑠派教団十二神将の一人で、ハエの昆虫人間(インセクトヒューマン)。十二神将の一人で、バッタの昆虫人間。昆虫人間としては試作品で、十二神将一の出来損ないと罵られている。甲虫類特有の硬い皮膚を持っているのでバトルスーツを必要としないことを誇っていたが、皮膚の極端な硬度を逆手にとられ(外骨格故に関節が脆い)手足を折られて倒された。

MLBの解説を担当。後述の通り現在は「プロ野球ニュースで綴る プロ野球黄金時代」を担当。 VE2022「ヤクルト×巨人」の実況を担当した。子育て支援給付その他の子ども及び子どもを養育している者に必要な支援を行い、もって一人一人の子どもが健やかに成長することができる社会の実現に寄与することを目的とする。二次健康診断等給付については、支給制限の問題は生じない(平成13年3月30日基発第233号)。長久手の戦いが起こり、家康は主力の指揮を執り尾張国に向かい、昌幸は越後の上杉景勝を牽制するために信濃に残留した。

円楽の生前は表舞台に立つことはなかったが、婦人公論2023年3月号で所属事務所オフィスまめかな社長・入門当時は落語協会に在籍しており、脱退後は五代目が創設した五代目圓楽一門会に所属、のちに桂歌丸が会長を務めた落語芸術協会(客員)との二重所属となった。

佐保明梨・菅谷梨沙子、℃-uteの中島早貴の4名での結成が発表され、同年5月27日にシングル「おまかせ♪ガーディアン」でデビューした。 の新垣里沙と、同じくモーニング娘。 「月島きらり」役の久住小春と、当時ハロプロエッグだった「雪野のえる」役の北原沙弥香・ SS Character Songs 02 三沢真帆

三沢真帆(井口裕香) 「マホトピア」 テレビアニメ『ロウきゅーぶ!傷口を塞ぐ役割を持つ細胞。

メモルゼ星人特有の「男女変換能力」を有しており、くしゃみをすると男性人格のレンと逆転してしまう。

2000年5月:本社東京事務所を三重県鈴鹿市へ移転。 “みずほ銀行に業務改善命令、提携ローンに反社会的勢力との取引”.

そんな過去からか、賭け事と色事で生計を立て、自由奔放かつ自堕落な生き方をしていたが、負傷した八戒を拾い、介抱したことをきっかけに三蔵達とも出会い、生活が一変する。全国興行生活衛生同業組合連合会 (2020年5月22日).

2022年11月25日閲覧。

名前の「和美」の読みから主人格を男の「カズヨシ」、副人格として女性の「カズミ」を持つ多重人格者。 それでも真面目な性格ゆえに無理に続けていたが、同居する母親がかなり前に死んでいたことに気づき(つまり同居人が死んだと気づかないくらいハードな生活だった)、悲しみから狂ってしまう。真面目で母親想いの青年。英国の求職者手当(Jobseeker’s Allowance, JSA)では、1人あたり給付額が毎年改正される。 このため高いプライドを傷つけられた母から、父に似ているという理由で虐待を受け、さらには少年時にペニスを手術で切り取られてしまう。父は平凡な男だったが、真野の幼少時に愛人を作って逃げていた。

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – тех профи

織田に仕えようとした昌幸に対し、上杉からの書状や家康からの指摘を元に厳しい態度で臨んだ。 “超高層マンション、鉄筋強度不足で部分解体 竹中工務店”.梶裕貴さんら出演声優も公開”.血液型:B型。血液型:O型。血液型:A型。 2021年10月11日閲覧。谷村昭仁「近江だるまに顔ほころぶ◇愛らしい表情が命 途絶えた歴史を復活し守り伝える◇」『日本経済新聞』朝刊2019年1月17日(文化面)2019年2月26日閲覧。

試合解説者とアナウンサーはシーズン中の担当曜日に関係なく週替わり。 2 交流戦や祝日等、月曜日に試合がある場合は別途定める。 プロレスに殉じた男 三沢光晴、21頁。金曜日は関根潤三が担当。利用開始当初はSMART ICOCAの列車利用ポイント(J-WESTポイント→WESTERポイント)の付与対象外であったが、2017年4月15日よりあいの風とやま鉄道線利用分もポイント付与の対象となった。

1 土曜日のみとなるオフシーズンも担当。 4 2009年以後のシーズンオフ期間は毎週月曜23:00に初回生放送(以後随時1週間後まで再放送)される。

箕輪城攻めに、信繁・ これでは敢えて三輪とする意義が薄くなってしまったのである。秀吉死後の慶長5年(1600年)に五大老の徳川家康が、同じく五大老の一人だった会津の上杉景勝討伐の兵を起こすとそれに従軍し、留守中に五奉行の石田三成らが挙兵して関ヶ原の戦いに至ると、父と共に西軍に加勢し、妻が本多忠勝の娘(小松殿)であるため東軍についた兄・

ノート博士の推察では、ルシュ国王が「文明を捨て、自然に還る」ことを実行した形跡が見られなかったことを主な理由として、後者の悪党説を真実と見ており、両者の意見を聞き比べたヂェーンも「いつ復活するか分からないアペデマスと一緒に(四戦士が)封印されるなんて、ほとんど謀反人と同じ扱いだ」と国王の欺瞞性を看破していた。人により評価が分かれ、自然を愛し「文明を捨て、自然に還る」ことを提唱した善き国王という意見もあれば(ナパ、バルカン、メロエはこの意見に賛成していたため、「ルシュ国王は素晴らしい人だ」と言っている)、自身の権力を守るために人気者であったアペデマスと五戦士に対し策謀を巡らせた老獪な悪党という意見もある。

和解後、惑星ガードンでの出来事などを経て、互いに好敵手のような関係となっている。 いつも自然体な野生児で団体行動が苦手。体力は低いが、峯明に次ぐ法術の使い手。年齢、血液型は不明。年会費等はかからない。 ロシア正教会、セルビア正教会など、ユリウス暦を使う正教会の降誕祭は、1月7日(ユリウス暦での12月25日)である(前述)。石森プロ.

2023年1月13日閲覧。

【岡山駅西口】 – (中鉄北部バス・岡山エクスプレス津山号) – 【津山広域バスセンター】

– (中鉄北部バス行方・土浦線) – 【土浦一高】 – (関鉄パープルバス下妻・

2024年7月21日は『FNS27時間テレビ』に競馬中継が内包される関係で、3場全てグリーンチャンネルと同じJRA公式映像からの中継となった。 2024年2月26日閲覧。 Twitter.

2010年8月12日閲覧。 2022年3月10日閲覧。 2023年6月26日閲覧。 】”. Twitter. 2017年9月28日閲覧。 アニプレックス (2010年9月27日). 2013年7月23日閲覧。 アニプレックス (2010年11月26日). 2015年10月13日閲覧。日経新聞の広告コラボ、その舞台裏に迫る」『アキバBlog』、2010年11月6日。 MANTANWEB. 毎日新聞社 (2010年10月5日). 2011年5月1日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。

多方面で知られた後は、コサキン内でこの曲がかかることは少なくなった。保険料改定率は、「各年度の前年度の保険料改定率」に、「当該年度の初日の属する年の2年前の物価変動率および当該年度の初日の属する年の4年前の年度の実質賃金変動率(3年前から5年前のものの3年平均)を乗じて得た率」(名目賃金変動率)を乗じて得た率とされる。二代目総長襲名後は二代目副総長の万代を勇ちゃんと呼び合う仲になっており、黒焚連合絡みの揉め事は全て万代の手により片付けられることと総長としての役割の少なささから万代に、しばらく総長を変わってくれと愚痴ることもあった。

経済学者である植草一秀は「日本政府が2010年欧州ソブリン危機に便乗して、日本の財政危機キャンペーンを実施している」と主張している。 ストアードフェア機能自体は通常のICOCAと同じ(ただし身体障害者割引等が適用されたICOCA定期券にはストアードフェア機能がない)で、ICOCAの前面に定期券情報が印字される(ただし四日市あすなろう鉄道・

なお、一部の事業者が発行している特割用カードは相互利用の対象となっていない。株主の受取配当の一部(一定割合または一定額)を所得税の課税標準算定過程で控除する方式。驚愕の担当マネージャー、小沢との交友を作り話で話す等、かなりの規格外の言動が目立った。 IMFも、格差の拡大は国の経済成長を阻害するという研究を出している。

1年を通じて勤務した給与所得者552,550,

597人、平均年齢約46.7歳、平均勤続年数約12.4年について。男性では1年を通じて勤務した給与所得者30,322,855人、平均年齢約46.7歳、平均勤続年数約13.9年について。所得金額階級別世帯数の相対度数分布をみると、「200~300万円未満」が13.6%で最頻値、「300~400万円未満」が12.8%、、「100~200万円未満」が12.6%、「400~500万円未満」が10.5%で中央値を含むと多くなっている。 500万円以下の者が平均年齢約42.8歳、平均勤続年数約11.6年で5,138,662人(同約16.9%)で最頻値、中央値を含む。

アニメ第1作では発芽せず、第3作では破片から発芽した。片言の日本語を話す。貸本版では、おばけ大学に入学して番長格を務める(初アニメ化「墓場」第10話)。 アニメ第4作と第5作では吸血樹の名称で登場(「妖怪樹」は別の話に登場)。第5作94話では沖縄に住み、千年前に封印されていた。 ただ、前述の通りその試合の9回裏2アウトの場面でライトフライを落球してしまい、それが原因でサヨナラ負けし、甲子園出場は逃した。頭の椰子の木を振り回して突風を起こし、椰子の実を弾丸のように飛ばす攻撃を使う。

たとえば小林昭二、中江真司といった本家ライダー関係者の起用、また木梨猛のファッションやノリダーのデザインは、かなり極端なデフォルメがされているものの明らかに「旧1号」(第1話 – 第13話の仮面ライダー)の本郷猛と仮面ライダー1号のデザインをもとにしており、ノリダーが乗っている50ccのバイクも初期のサイクロン号によく似せてある。 また、オープニング映像も本家と同じくノリダーがバイクで疾走するシーンが使われ、オープニング終了後の映像にも木梨猛が改造されるシーンと共に本家と同じようなナレーションが使われていた。 2019年に公開された『劇場版 仮面ライダージオウ Over

Quartzer』にて木梨猛役で木梨が出演。 その後、2007年(平成19年)9月27日放送の『とんねるずのみなさんのおかげでした』特番において放送された「もう一度みたい仮面ノリダーベスト10」において、初めて「協力:石森プロ・

laku toto laku toto laku toto laku toto

Pretty nice post. I just stumbled upon your weblog and wished

to say that I’ve truly enjoyed browsing your blog posts.

In any case I’ll be subscribing to your rss

feed and I hope you write again very soon!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту бытовой техники с выездом на дом.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт крупногабаритной техники в красноярске

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

14歳以上の子どもに対しては支給額が加算される。具体的には、以下のような事例の場合は支給される。 フェンスでは結果が振るわず、自己最低の総合14位タイに終わってしまった。自宅では猫を飼っており、第2期から2匹に増えた。第74話で妖怪を取り込みすぎたことで体はすでに限界を迎え始めるが、それに構わず玉藻前を倒すために子泣き爺、ぬりかべ、砂かけ婆を取り込み、ムジナの能力で玉藻前の分身に近づき戦うも返り討ちに遭う。

河床勾配が緩く、蛇行している川も多数流れることから洪水が起きやすい地域であったが、首都圏外郭放水路や権現堂調節池(行幸湖)、大相模調節池などが建設され、現在も利根川中流と江戸川上流の堤防を拡幅強化する首都圏氾濫区域堤防強化対策などの治水事業が行われており、浸水被害は減ってきている。

1928年(昭和3年)には、現在の近鉄名古屋線の前身である伊勢電気鉄道の桑名延伸(泗桑線)に際して、四日市市駅 – 諏訪駅間を廃止し、路線敷を伊勢電気鉄道に譲渡した。演歌名曲コレクション8 -冬のペガサス-勝負の花道〜オーケストラ – 33.

新・ コレクションVol.01〜演歌&歌謡曲の世界〜 – 40.

氷川きよし オリジナル・

2015年8月2日にも「TBSデリシャカス2015」会場から同様の「夏SUNSUNサンデー寄席」を公開生放送。 2017年7月23日には「デリシャカス2017」会場から「夏SUNSUNサンデー寄席2017」を公開生放送。 なお、この公開生放送の直前には、うしろシティとハライチが出演する『デブッタンテ』の公開収録が行われた。 くまもと復興応援感謝フェア」の一環で、15時台にネタ中に「くまモン」を織り込むことを条件とした「サンデーくまモン寄席」を公開生放送。 871の同級生。 14時台の「ちょースッキリ評議会」を13時台に移動させ前回より拡大した。 「サンデー芸人反省会」も「サンデー競馬小僧」を休止し拡大した。 Aマッソ、脳みそ夫、ペンギンズ、アキラ100%、BOOMERが出演した。

九本の尾を生やし、強大な妖力を持つ妖狐。変身能力を持っており、ユニコンの鏡を取り戻しに来た子供達の一人・ キバ男爵配下の戦闘員は上腕部に2本のキバが交差したマークが入っており、トーテムポールへの変身も可能。 プルトーの手下で、半竜人(はんりゅうにん)ともいう。 サタンに仕える八人の死神の一人で、黒縄地獄を支配している。伝承では人間の男性を堕落させる女悪魔の最高長官と言われる独立部隊の一匹狼の悪魔で、サタンからの命令はあまり受けないとされているが、本作ではサタンに仕える八人の死神の一人。

Simply desire to say your article is as amazing. The clearness in your

post is just cool and i can assume you’re an expert on this

subject. Well with your permission allow me to grab your feed to keep updated with forthcoming post.

Thanks a million and please carry on the rewarding work.

電撃大賞にて2001年12月に「人の痛みが分かる国」、「絵の話」、「レールの上の三人の男」、「本の国」を放送。時雨沢恵一(原作) / 黒星紅白(キャラクター原案) / 電脳桜蛙団(作画) 『学園キノ』 アスキー・

1972年、上福岡市立第二小学校(現・ ガラス業界は寡占化が進む板ガラス業界とそれぞれのガラス製品の特性を生かした多数の中小企業に二極化される。同年4月上福岡市立第二中学校(現:

ふじみ野市立葦原中学校)に入学、1981年3月同校卒業。

そのことがきっかけで自ら児童文学を読むようになり、父親も文学に興味があるため家には大量に本があり、光が欲しがるならば本を買い与えた。

ただし給付を受ける者が未成年後見人たる法人である場合、所得制限は行われない。 2年春の選手権大会の無差別級個人戦で橘を破って日本一になるなど、作中で巧と戦った世代では橘と並んでトップクラスの実力を誇っていた。 インカム(BI)」制度が具体的に何を指すのか定かではありませんが、一般的にBI制度とは、「全ての国民に生活に最低限必要なお金を支給する」制度であるとされています。給付費の負担は、原則として国:都道府県:市町村=4:1:1で負担し、それに一般事業主からの拠出金が加わる。

2021年1月5日、第5試合のIWGPジュニアヘビー級選手権試合で、前日に『SUPER J-CUP』優勝者のファンタズモを下した『BEST OF THE SUPER

Jr.』優勝者のヒロムと対戦。日本テレビホールディングス(公式ウェブサイト) ※アニメ作品およびテレビ番組の製作と利用。刃牙と共に松本家に住んでおり、梢江や絹代にも懐いている。 2月19日、第6試合でIWGPジュニアタッグ選手権試合4WAYマッチで王座に挑戦。 2022年1月5日、IWGPジュニアタッグ選手権試合3WAYマッチで王座に挑戦。

真戸はリョーコの遺体でヒナミをおびき出し、ヒナミを探しにやってきたトーカと対峙する。 トーカの攻撃で致命傷を負った真戸は、彼女ら喰種に対し激しい憎悪と侮蔑の言葉を吐きながら死亡する。戦闘当初は菊地原のサイドエフェクトによって敵の攻撃を上手く避けたり、ステルス戦闘での攻撃を仕掛けるが、「泥の王」の(気体(ガス)ブレード)によって緊急離脱してしまう。 1月 – 大阪府立体育会館大会で川田に垂直落下式ブレーンバスターで敗れ、王座転落。

そこで人肉を分け与えてもらうが、空腹による飢えと、人としての尊厳を守ることとの間で激しく葛藤するカネキは、精神的にも肉体的にも追い詰められていく。

標本にした生物の能力を自分のものにする妖力を持ち、首に付いた串以外にも掌から多数の串を投げて攻撃する。 “カボチャ|基本の育て方と本格的な栽培のコツ | AGRI PICK”.

』”. 価格.com テレビ紹介情報. 2021年1月18日閲覧。 2021年9月5日閲覧。 サカタのタネ. 2021年7月14日閲覧。 Malia Frey (2021年11月4日). “Pumpkin Nutrition Facts and Health Benefits”. “.

ちそう. KOMAINU (2021年7月6日). 2021年7月11日閲覧。 “. 大分県立図書館.大分県立図書館.

Appreciating the hard work you put into your site and in depth information you provide.

It’s great to come across a blog every once in a while that isn’t the same outdated rehashed information. Fantastic read!

I’ve saved your site and I’m including your RSS feeds to my Google account.

劇中で正体を見せた他の昆虫人間たちは基本的に人間に近い体型のようだが、彼はほとんど「巨大なカブト虫」といった容姿で、昔の公家に似た顔がついている。十二神将の一人で、カブト虫の昆虫人間。外魔瑠派教団十二神将の一人で、ハエの昆虫人間(インセクトヒューマン)。十二神将の一人で、バッタの昆虫人間。昆虫人間としては試作品で、十二神将一の出来損ないと罵られている。甲虫類特有の硬い皮膚を持っているのでバトルスーツを必要としないことを誇っていたが、皮膚の極端な硬度を逆手にとられ(外骨格故に関節が脆い)手足を折られて倒された。

一方、徳川家康は相模国の北条氏直と連携しており、真田領は両勢が衝突する地点となった。徳川勢は甲府から新府城(山梨県韮崎市中田町中條)を通過して上田城へ向かい、昌幸は越後国の上杉景勝と連携して徳川勢と戦った。砥石城攻略後、天文23年(1554年)8月に武田氏は南信濃の伊那郡の国衆を服属させると北信濃へ侵攻し、北信濃の川中島四郡をめぐり越後の長尾景虎との川中島の戦いが繰り広げる。

三重県県土整備部”三重県の道路/県管理道路一覧”(2013年1月24日閲覧。 13 May 2020.

2020年5月14日閲覧。 レッスンや芸能活動に加え、アキ・海岸の塚に封じられていたが、何者かに封印石を壊されて復活し、海水浴客の影を食い昏睡状態に陥れるが、最後は弱点を見破られ、封印石で再封印される。最後は鬼太郎に敗北し、地獄へ送還される。

あまりにも鈍過ぎる光にイヤミを言う事もあるが、もちろん鈍過ぎて伝わらずに余計にショックを受ける事も。村枝賢一による漫画『仮面ライダーSPIRITS』では、『V3』に登場しなくなってから『仮面ライダーZX』までの作中時間の経過を反映して年齢を重ねた容姿となり、インターポールの本部長として10人ライダーの戦いをサポートする姿が描かれている。日曜以外に実施される場合も原則として土曜日の放送時間帯での放映となる(ネット局は別途定める)。 これにより朝ドラのソフトとして歴代トップかつ初の総合ベスト3入りを果たした。 『EXILE、三代目JSBら総出演!幼い頃から同年代の子供と遊んでも彗の超人さに相手が付いていけず泣き出すため、彗自身も株の動きを見るなど一人でいる方が楽しい子供だった。

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – техпрофи

修と風間の模擬戦以来、何かと修に絡むことがあるが、普段は風間隊の隊員以外と話し込むことなどほとんど無いので、目撃した時枝は遊真に「あの二人は仲がいいの? スゴ腕の専門外来」SPが放送開始、初代司会は高橋克実と優木まおみ。趣味は映画鑑賞、読書。学校近くの古本屋に通い本を読みあさったり、映画を見続ける日々を送っていた。高校卒業後、夜間の大学へ進学。 1993年2月2日、東京都渋谷区生まれ。西日本旅客鉄道、2023年2月17日。

おおらかで男性職員(シン宮基準のいい男)に絡むのが好きな中年女性。半年後の10月から19:30-19:55に落ち着く。現在は「放課後☆華園CLUB」の会員でもあるらしい。報道ドキュメンタリー番組。 ABCニュース『ナイトライン』や1984年から関東甲信越地域で放送されている『特報首都圏』に進行構成で類似性が見られる。順番は都道府県コード、地方区分は行政による。 4月放送分より、番組公式ウェブサイト上にて過去の放送の視聴率(ビデオリサーチ調べ、関東地区・

試合後、出会えた証として天馬に自らのミサンガを手渡し、彼に感謝しながら妹の所へ旅立った。音楽制作 –

フジパシフィック音楽出版、ソニー・東京新聞杯 28,290円的中 × × × 芸人枠は竹山、女子枠は椎名。事件解決後は本庁に異動になり、新居田の部下になる。最高裁判所も2017年3月21日判決で大阪高裁の判決を支持し、当該規定が合憲であることが確定した。

“ぐるっと流山 流鉄ビア電車”. “大人番組リーグ:レギュラー化決定 濱田岳主演の「お先にどうぞ」など4本 7月から放送”.

毎日新聞デジタル.恋愛向上委員会(流田まさみ):1999年12月号・ 『B’s-LOG』2014年6月号、エンターブレイン、2014年4月19日。 “. J-WAVE NEWS (2017年4月29日). 2021年11月1日閲覧。 J-WAVE NEWS (2017年11月25日). 2021年11月1日閲覧。 」”.

J-WAVE NEWS (2017年11月10日). 2021年11月1日閲覧。男性ウケする「もてメイク」”. J-WAVE NEWS (2017年11月18日). 2021年11月1日閲覧。

Honda ウェルカムプラザ青山 (2014年2月15日).

2015年1月6日閲覧。武田家が滅亡する直前には昌幸とも信頼関係が芽生え始めており、新府城を捨てるときには昌幸を生かすべく彼の領地にある岩櫃城ではなく小山田領にある岩殿城に移ることを進言する。織田家の甲斐侵攻に際して自領にある岩殿城へ移るよう勝頼を説得するも、家臣の反発に遭い勝頼を裏切る。織田軍の甲州征伐で高遠城を落とされた後、「最期を迎えるなら父祖伝来の甲斐にしたい」という思いから昌幸の岩櫃城へ移る案を退け岩殿城へ移ろうとするも、小山田信茂の裏切りで叶わず、天目山で自刃する。

川添との沖縄グルメリポートが放送された関係で、湯舟は2018年3月28日(水曜日)の同コーナーにて入矢との尾道の旅が放送された関係で、非担当曜日ながらオープニングから出演(スポーツコメンテーターは所定の人物が担当)。 3月7日から月曜日のスポーツキャスターを担当。 「けさのクローズアップ」にて自身の私生活に関連した内容の時に担当。 キャッシュカードには誕生日、住所番地、電話番号等、第三者に推測されやすい暗証番号を用いない。朝日放送→朝日放送テレビアナウンサー以外のレギュラー出演者が1週(5日)間を通じて代行することは、過去のアシスタントの休演期間中を含めても異例であった。

拼音: Shànghǎi Wèilái Qìchē)は、中華人民共和国の自動車会社。遊真の黒トリガー争奪戦後は近界民に偏見を持たない迅が自分と似た境遇であること、敵であるはずの近界民の遊真がボーダーに対して協力的なことなどを知り、それまでの自分の価値観と周囲とのギャップに動揺することになる。 Sd Kfz 2 – ケッテンクラート:第二次世界大戦時に製造されたドイツ国防軍の特殊車両。 2016年 – NIOブランド立ち上げと同時にEP9が発表された。最大の長所は交換時間の短さであり、バッテリー交換に要する時間は5分以内。

昌幸に扮する草刈をデザインした「信州上田観光プレジデントクリアファイル」を新たに製作し、「特別企画展」来場者に記念品として進呈するなど、放送終了後ほぼ1年にわたって放送中同様に番組関連の企画を実施している。若い頃の旅の話もキノにしており、キノには他人に自分のことを聞かれても白を切るようにと注意している。真田家ゆかりの山家神社(上田市真田町長)では2017年以降、2月3日の節分厄除大祭にて出演者らによる豆まきを開催しており、2017年には長野・

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту бытовой техники с выездом на дом.

Мы предлагаем:ремонт бытовой техники в ростове на дону

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

кондиционер ремонт

Сервисный центр предлагает качественный ремонт кондиционеров hiberg сервис ремонта кондиционеров hiberg

сервисный центре предлагает ремонт телевизоров в москве ремонт тв – ремонт телевизора на дому в москве недорого

捕捉した相手の背面から2発、正面に回り1発の拳撃を入れる。 『EX』シリーズでは腕の構え方が他のシリーズに比べ異なり、画面の奥行きへの移動を伴う。家の前で起きた抗議行動のストレスで発作を起こし急死した。発動と同時に完全無敵となり、その間は相手の攻撃を受け付けないが、終了後に隙がある。 『スト6』では特殊技入力となったが無敵は削除され、構えも短縮された。 ヒットすると追加入力で派生。 8月1日 – 宮城県と地産地消の推進や地域の農林水産物、加工品の販売に関すること等「連携と協力に関する包括協定」を締結。

Сервисный центр предлагает починка кофемашин aresa качественый ремонт кофемашины aresa

震源域が島のすぐ近くであったため、地震発生から数分で奥尻島に巨大津波が到達したことが、この地震の特徴となっている。 また、地震発生の4分から5分後に、奥尻島の対岸にある北海道南西岸の瀬棚町や大成町(いずれも現・奥尻島の各地区における津波の高さ(波高)は、稲穂地区で8.5

m、奥尻地区で3.5 m、初松前地区で16.8 mに達した。

古代の秘術により不老不死となっているが不完全なもので、実際には長い時間をかけて徐々に肉体は朽ち、脳細胞も既に全て活用しきっているために物覚えが悪い。 「子供と妖怪の相性の良さ」が常人よりも突出しており、この性質の指向性を自覚的に制御することで動物型の妖怪の口寄せを行うことが可能。特許切れの長期収載品「アクトス錠」などの7製品を追加して、武田テバファーマの全額出資子会社「武田テバ薬品」に移管、譲渡した。

ある日、半沢が融資課長として勤める東京中央銀行大阪西支店で、支店長の浅野匡から、これまで取引のなかった西大阪スチールへの融資検討の話が持ち上がる。下野新聞SOON (2011年3月27日).

2011年3月28日閲覧。 サンクスに残留した店舗はサンクス西四国管内の店舗と同様、2015年3月から8月にかけてサークルKにブランドが変更された。 2020年3月4日閲覧。 30 April 2020.

2020年9月22日閲覧。 AppleInsider. 2022年10月24日閲覧。

『大衆人事録 第二十三版 西日本編』広瀬弘、帝国秘密探偵社、1963年8月10日、う167頁、き324頁。朝日新聞 (2010年10月13日).

2015年10月24日閲覧。 FARFE (Foundation for the Advancement of Research in Financial Economics) (2010年12月10日).

2015年1月20日閲覧。 “Press Release Announcing the Second Ross Prize: Economics Scholars Nobuhiro Kiyotaki and John Moore Recognized” (英語).

“19 January 2015: BdF – TSE Prize Ceremony in Monetary Economics and Finance.” (英語).

夫の存在〜 – ファースト・ X’smap〜虎とライオンと五人の男〜 – まほらのほし

– 電車男 – 純情きらり – 誰よりもママを愛す – 家族〜妻の不在・ 〜こづかい3万円の恋〜 –

アベレイジ – ケータイ捜査官7 – ハチワンダイバー – 魔王 – アベレイジ2 – 我はゴッホになる!

I savour, result in I discovered just what I was having a look for.

You’ve ended my 4 day lengthy hunt! God Bless you

man. Have a nice day. Bye

駅伝】 関東学生陸上競技連盟(関東学連)は、第101回以降の箱根駅伝の参加資格を「関東学生陸上競技連盟男子登録者」に限定することを発表。

カルロスの代わりにボランティアに参加した際、交通事故で死亡してしまう。第10回大阪マラソン兼第77回びわ湖毎日マラソン統合大会(2月27日、大阪府大阪市中央区・

紀元前20万年ごろ、土星の衛星タイタンにあるオヴァロンの秘密基地にロワ・ ただしガミラス本星は外殻が二重になっているだけで空洞惑星ではない。勝平は泣きながら浜本に謝罪した。 が、オイルショックにより燃料代が高騰したことにより生産量は1987年には2790頭と激減した。

ちなみに、合金を作る際に混ぜる金属は、割り金と呼ばれ、例えば銅を混ぜると赤っぽくなるほか、鉄は緑、アルミニウムは紫になる。各ユニットには、「属性補正」というパラメータがあり、これによって、各属性の相手に対して、本来の攻撃力の何%分の攻撃力が発揮できるかを示している。

数日前に「金色の郷」から突然姿を消した若い従業員。惑星ツァリトに駐在するテラ工作員。惑星グレイ・ビーストに流された流刑囚。 のちにローダンに指導者の素質を認められ、同星に築かれた植民地のリーダーとなる。紀元前20万年ごろの惑星ツォイト出身の生物。元真正民主主義同盟メンバーだったが、ローダンの暗殺に失敗して流刑に処された。

全中の緊急報道編成が行われたため、急遽BSプレミアム・寮ブロックは完全なデコイであり、囚人達は地下全体を使った監房ブロックに押し込められ、衣食住を保証した上で基本的に「何もさせない」でおかれている。 ロイター通信日本語版 (2020年1月17日).

2020年1月17日閲覧。 ニ六事件で暗殺され、日本の経済は歯止めが利かなくなっていった。 しかし、放送中断後、「臨時ニュースが挟まるなど聞いていない」等、視聴者から8万5千件に及ぶ苦情がNHK総合テレビから抗議電話・

Если вы искали где отремонтировать сломаную технику, обратите внимание – выездной ремонт бытовой техники в воронеже

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту компьютеров и ноутбуков в Москве.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт макбуков

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Тактильная это простыми словами.

Красно фиолетовый цвет глаз.

Интуиция простыми словами. Учиться психологии онлайн. Установите

соответствие между понятием

и определением личность человек талант индивид.

Скачать фильм воспоминания 2021 через торрент бесплатно в хорошем качестве.

Синоним познания. Тест 24 ру.

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту кофемашин по Москве.

Мы предлагаем: сколько стоит ремонт кофемашины

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту бытовой техники с выездом на дом.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт крупногабаритной техники в тюмени

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту кондиционеров в Москве.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт кондиционера москва

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту гироскутеров в Москве.

Мы предлагаем: сервис по ремонту гироскутеров

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту моноблоков в Москве.

Мы предлагаем: замена экрана моноблока цена

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Профессиональный сервисный центр по ремонту планшетов в том числе Apple iPad.

Мы предлагаем: ремонт ipad москва

Наши мастера оперативно устранят неисправности вашего устройства в сервисе или с выездом на дом!

Сервисный центр предлагает замена стекла sony xperia tablet z замена камеры sony xperia tablet z