Hannah Askari took the ‘Philosophical Britain‘ module at Queen Mary in 2015. In this post she writes about ‘Individualism’ as a philosophical keyword.

Image from http://www.spectator.co.uk/features/8940211/in-defence-of-individualism/

Individualism (a)

‘The habit of being independent and self-reliant; behaviour characterized by the pursuit of one’s own goals without reference to others; free and independent individual action or thought.’[1]

I began my research with a simple Google of ‘individualism.’ It resulted, interestingly, with the discovery of a website titled Individualism. After a few more searches I found that this website has wholeheartedly embraced social media and also has a Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr, and a Facebook page. The website describes itself, rather paradoxically, as ‘a collective dedicated to celebrating men’s style.’ It’s a place where you (and the rest of the internet world) can find tips and tricks on how to express your individuality aesthetically. For myself, this online faction exemplifies what ‘individualism’ means today in the twenty-first century.

To be ‘individual’ can today often compliment a person with a unique fashion sense or eccentricity; something the website is adhering to. However, ‘individualism’ is still also a word with a range of connotations. It is a political philosophy that puts the individual’s moral worth at its centre. Left-wing commentator, columnist and author Owen Jones complains about the promotion of ‘dog-eat-dog individualism’[2] of contemporary Tories as a replacement for strong working-class values such as community and solidarity. In this sense, to be ‘individual’ is often associated with selfishness, egotism and greed; adjectives that most would agree is not particularly desirable.

Nonetheless, the political and aesthetic ideal of ‘individualism’ actually has a much longer history.

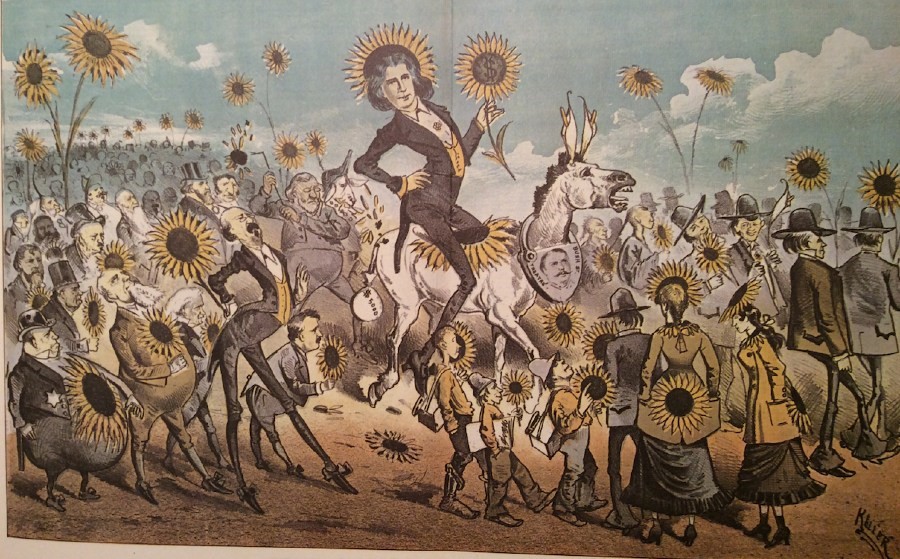

Oscar Wilde, is arguably one of the primary figures when thinking about aesthetic individualism. His flamboyant philosophy justified his colourful persona; which is articulated through fictional characters in his literature and essays. Wilde believed in the value that ‘aesthetics are higher than ethics’[3]; he believed the superior aim in life was to be able to ‘discern the beauty of a thing.’[4] His philosophy was an attack on the old-fashioned Victorian values of altruism. He, and other anti-altruists ‘wanted to create a new moral language and a new kind of ethics’[5]; one which focused on art and the individual. Although Wilde’s philosophy of aestheticism was not totally new or original, it did allow a real distancing from Victorian tradition. Wilde’s provocative interpretations are exemplified in De Profundis in which he writes of Christ that:

People have tried to make him out an ordinary philanthropist, or ranked him as an altruist with the unscientific and sentimental. But he was really neither one nor the other[6]

Ultimately, Wilde puts forward Christ as ‘the most supreme of individualists’[7] and proposes that one should be helpful and charitable to others, not for their benefit but for one’s own self-fulfilment.

Oscar Wilde: flamboyancy in picture form. Image from http://www.oscarwildeinamerica.org/features/the-modern-messiah.html

Degeneration theorist, Max Nordau, said that Oscar Wilde’s aesthetic individualism was only ‘a purely anti-socialistic, ego-maniacal recklessness and hysterical longing to make a sensation.’[8] Understandably for the conventional Victorian, Wilde was the incarnation of the signs of a troubling modern culture in the 1890s.

In the 1890s, English philosopher G.E. Moore was inspired by Oscar Wilde, and began to compare the importance of altruism and egoism as ethical moralities. He was asking himself questions such as ‘are we selfish?’ and ‘do we love ourselves best?’[9] His 1903 publication Principia Ethica, settles that:

Egoism is undoubtedly superior to altruism as a doctrine of means; in the immense majority of cases the best thing we can do is to aim at securing some good in which we are concerned, since for that very reason we are more likely to secure it.[10]

Principia Ethica is an innovative philosophical enquiry into what it is that constitutes ‘good’. For the forward thinking Bloomsbury Group it became a sort of Bible and laid the philosophical groundwork of their aesthetic principles. For both Moore and those of the Bloomsbury Group, the ethical ‘good’ was embodied by the importance of individual relationships and personal life. Moore furthered Wilde’s belief that detection of beauty ‘is the finest point to which we can arrive,’[11] defining beautiful as ‘that of which the admiring contemplation is good in itself.’[12] For G.E. Moore, it was in the goodness of art and beauty in which one found moral meanings, not in philanthropy and thinking of others.

Individualism (b)

‘The principle or theory that individuals should be allowed to act freely and independently in economic and social matters without collective or state interference.’[13]

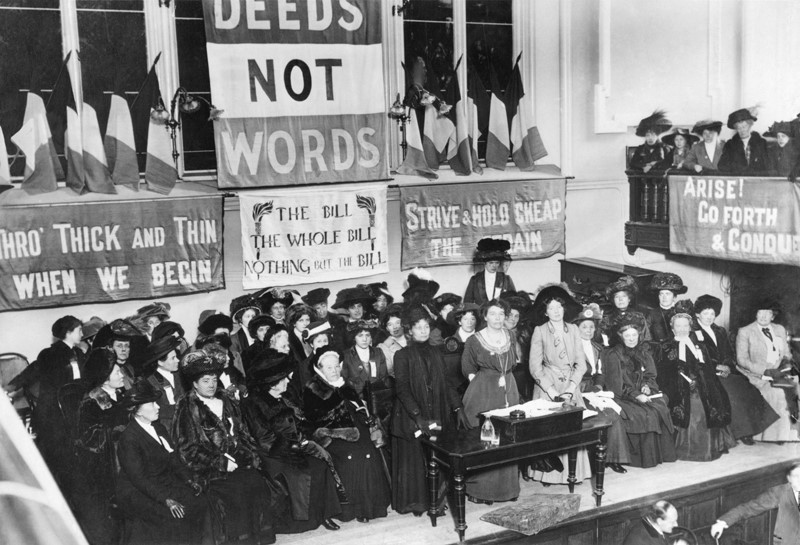

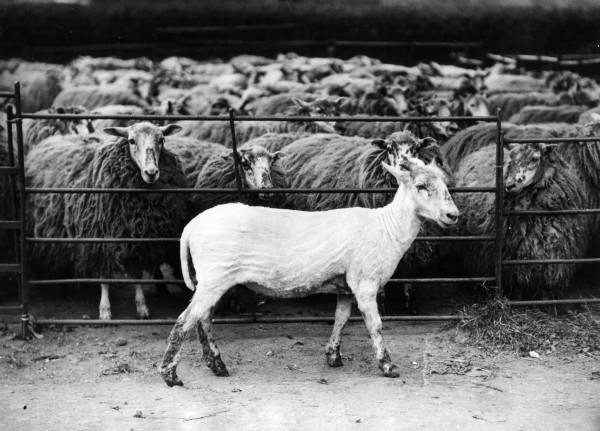

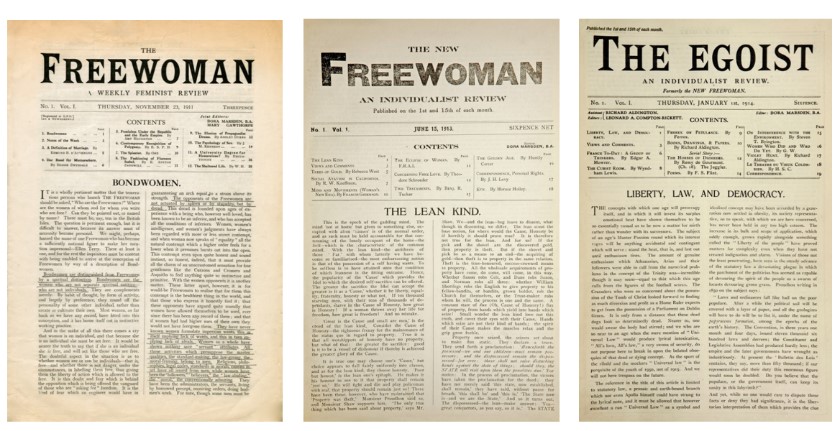

Anarchist-feminist Dora Marsden worked for the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU ) but became motivated to express her individualism. She was known for her involvement in serious political demonstrations; which eventually led to a formal break from the WSPU. She established her own magazine near the end of 1911: The Freewoman: A Weekly Feminist Review. She wished to advocate a feminism which dealt with more than just suffrage; a ‘third-wave way before her time.

Dora Marsden being arrested for her suffragette activism in Manchester 1909. Image from Greater Manchester Police Museum

It was Max Stirner’s The Ego and his Own, which offered a philosophy dedicated to individualism that influenced Marsden even further. Stirner argues self-mastery is only able to exist when the individual is free from all obligations, only then than the individual be sure that they are never used by others for their ends but only by the individual for the individual’s own ends. Stirner believed that a platform concerned with the welfare of groups would ruin those exceptional individuals.

It was this concept of the individual (and the lack of funding) for The Freewoman, which drove Dora Marsden to create The New Freewoman: An Individualist Review; It followed that:

The New Freewoman is not for the advancement of Woman, but for the empowering of individuals—men and women; it is not to set women free, but to demonstrate the fact that “freeing” is the individual’s affair and must be done first-hand[14]

The New Freewoman was a short-lived publication and by January 1914 it had morphed into The Egoist: An Individualist Review. The Egoist became one of the primary magazines of modernism, and was home to a number of influential literary artists, such as Ezra Pound, Wyndham Lewis, T. S. Eliot. Moreover, James Joyce’s first novel, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man was printed as a serial in The Egoist.

Marsden’s transformation to Stirnian individualism can actually be seen as a natural development. It all began as a protest against the Pankhursts’ methods and rejected the idea that the women’s movement was dependent on the sacrifice of individualism. Her magazines are a satisfying evidence for her changing and evolving perspective; firstly as a supporter of democratic suffrage and then an advocate of anarchistic individualism.

Nevertheless it was not Dora Marsden who Russell Brand called the ‘icon of individualism.’[15] That instead is Margaret Thatcher, of course! Thatcher is often criticised for having ‘implanted the gene of greed in the British soul’[16], epitomised by the onslaught of the ‘yuppie’ culture. Aspiration became the thirst for a bigger ‘thing’ like a car, or house.

Following Thatcher’s death in 2013 there was a surge of discussion around her infamous quote:

There’s no such thing as society. There are individual men and women and there are families. And no government can do anything except through people, and people must look after themselves first. It is our duty to look after ourselves and then, also, to look after our neighbours.[17]

Thatcher, like many before her, saw individualism as an important aspect of life. Unfortunately her premiership has, and still does, create fierce debate. When David Cameron won the Conservative Party leadership in 2005 he stated that ‘there is such a thing as society, it’s just not the same thing as the state.’[18] He wanted to distance himself from the controversy which surrounds Thatcher who is still associated with a selfish and uncaring individualism.

Oscar Wilde once said that individualism ‘seeks to disturb the monotony of type, slavery of custom, tyranny of habit, and the reduction of man to the level of a machine.’[19] We are closer today than ever before to turning man into a machine and individualism is under threat. How interesting would it be to ‘do’ an Oscar Wilde, a Dora Marsden, even a Margaret Thatcher, let the individual loose and disturb … absolutely everything?

Further reading:

Dixon, T The Invention of Altruism: Making Moral Meanings in Victorian Britain, (Oxford: Published for the British Academy by Oxford University Press, 2008)

Clarke, B. Dora Marsden And Early Modernism (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996).

Wilde, O. et al., The Complete Works Of Oscar Wilde (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

Brown, S. L. The Politics Of Individualism (Montréal: Black Rose Books, 1993).

Meiksins Wood, E. Mind and Politics: An Approach to the Meaning of Liberal and Socialist Individualism. (University of California Press, 1972)

Bibliography

Clarke, B. Dora Marsden And Early Modernism (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996).

Dixon, T. The Invention Of Altruism (Oxford University Press, 2008)

Jones, O. Chavs: The Demonization of the Working Class, (London: Verso, 2011)

Wilde, O. et al, The Complete Works Of Oscar Wilde (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000)

Websites

The Spectator Archive, 1828-2008

References:

[1] [1] Oed.com, ‘Individualism, N. : Oxford English Dictionary’, 2015, http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/94635?redirectedFrom=individualism&.

[2] Owen Jones, Chavs: The Demonization of the Working Class, (London: Verso, 2011) p. 71.

[3] Oscar Wilde et al, The Complete Works Of Oscar Wilde (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000). Vol. 4 p. 204. All sentiments are put forward by Gilbert in ‘The Critic as Artist’ first published in Intentions (1891)

[4] Ibid.

[5] Thomas Dixon, The Invention Of Altruism (Oxford University Press, 2008). p. 322

[6] Oscar Wilde et al. (2000) vol. 2, p. 176.

[7] Wilde et al. p. 176

[8] Max Nordau, Degeneration, (University of Nebraska Press 1993) p. 319. In Thomas Dixon, The Invention of Altruism, p. 333.

[9] Apostles papers given by Moore on 26 Feb. 1898 and 4 Feb. 1899. In Dixon 2008, p. 354

[10] G. E. Moore, Principia Ethica, (Cambridge University Press, 1993) p. 216 in Ibid.

[11] Oscar Wilde et al. (2000) p. 204.

[12] G. E. Moore (1993) p. 249

[13] Oed.com, ‘Individualism, N.: Oxford English Dictionary’, 2015, http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/94635?redirectedFrom=individualism&.

[14] ‘Views and Comments’, The New Freewoman: An Individualist Review, (July 1st 1913), vol.1 no. 2., p. 25 http://library.brown.edu/pdfs/1303305900625129.pdf

[15] Russell Brand, ‘Russell Brand On Margaret Thatcher’, The Guardian, 2013, http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2013/apr/09/russell-brand-margaret-thatcher.

[16] Simon Kelner, ‘Mrs Thatcher implanted the gene of greed in Britain’, The Independent, 2013, http://www.independent.co.uk/voices/comment/mrs-thatcher-implanted-the-gene-of-greed-in-britain-8565716.html

[17] Interview for Woman’s Own, 1987. http://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/106689 [last accesses 06/03/2015]

[18] David Cameron, ‘BBC NEWS | UK | UK Politics | In Full: Cameron Victory Speech’, News.Bbc.Co.Uk, 2005, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/4504722.stm.

[19] Oscar Wilde et al., p. 260

On February 27th, 2015, there began a worldwide debate about the colour of a dress. A picture of

On February 27th, 2015, there began a worldwide debate about the colour of a dress. A picture of