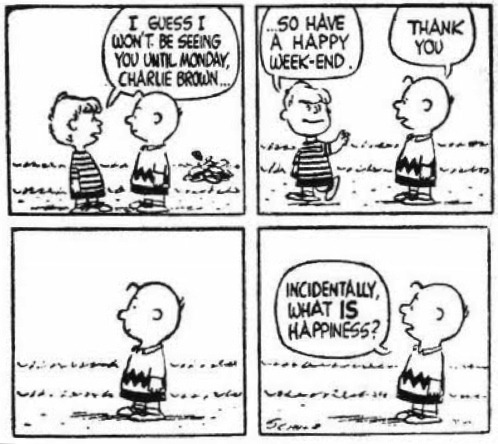

Charlie Roden took the ‘Philosophical Britain‘ module at Queen Mary in 2016. In this post she writes about ‘happiness’ as a philosophical keyword, with the help of Charlie Brown.

Extract from the comic-strip ‘Peanuts’. Image from http://www.philipchircop.com/post/15448312238/incidentally-what-is-happiness-do-whatever

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, ‘happiness’ is defined as ‘the state of being happy’, that is, ‘feeling or showing pleasure or contentment.’[1] Happiness is a universal concept which, I believe, most people aspire to achieve. However, since happiness is so subjective, everyone interprets it in different ways.

Many people believe that they attain happiness when they eat their favourite food, buy new clothes or earn a lot of money. Although these are all experiences that can be enjoyed, they don’t actually cause happiness- they only bring us pleasure. Of course, the official definition of ‘happiness’ does include pleasure, however I agree with Happiness International who suggest that pleasure is only short-lived and externally motivated. If happiness relied on pleasures such as the ones just mentioned, does this suggest that without a lot of money or materialistic items people are unhappy?

I don’t believe that anyone can truly define ‘happiness’, and by looking at the history of this word we can see how its cultural and philosophical meanings have changed over time, demonstrating that happiness cannot simply be understood as a single concept.

‘Happiness’ stems from the late fourteenth-century word ‘hap’ meaning ‘good luck’ or ‘chance’. [2] This suggests then that in the Middle Ages, a person was believed to be happy if they had good fortune. Already, we can see how a modern perspective of ‘happiness’ is different to this idea, as although being lucky can promote happiness, we can often feel happy without being fortunate.

The sole predecessor to the idea of ‘happiness’ was proposed by Aristotle (384-322 BC). In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle emphasised that the ultimate aim in life is ‘Eudaimonia’, an Ancient Greek term usually translated as ‘happiness’ or ‘human growth.’ [3]

Unlike an emotional state, such as pleasure, Aristotle asserted that Eudaimonia is about reaching your full potential and flourishing as a person. In order to do this, you need to live a life that is wholesome and virtuous to attain the best version of yourself. [4] Virtue can be achieved through balance and moderation, as this way of life leads to ‘the greatest long-term value’ rather than just pleasure that is short-lived. [5] In a modern-day perspective, this would be the difference between earning vast sums of money but spending it all at once, as opposed to spending money wisely, ensuring it will last and provide you with a good life. [6]

In the early modern era, the importance of happiness began to emerge in the political sphere. [7] In 1726, the Scottish philosopher Francis Hutcheson (1694-1746) wrote that

‘that Action is best, which procures the greatest Happiness for the greatest Numbers; and that, worst, which, in like manner, occasions misery.’ [8]

This utilitarian principle, which aims at the greatest happiness of the greatest number, essentially asserts than an action is right if it produces happiness and wrong if it produces the reverse of happiness. [9]

Jeremy Bentham, image from http://sueyounghistories.com/archives/2010/06/13/jeremy-bentham-1748-%E2%80%93-1832/

The most famous advocate of utilitarianism was English philosopher and jurist Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832). Bentham proposed many social and legal reforms, such as complete equality for both sexes, and put forward the idea that legislation should be based on morality. [10] Identifying the good with pleasure, in his 1781 book An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, Bentham wrote:

‘Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure. It is for them alone to point out what we ought to do, as well as to determine what we shall do.’ [11]

By stating that happiness can be understood in terms of the balance of pleasure over pain, Bentham shares an ethical Hedonistic claim; the notion that only pleasure is valuable, and displeasure or pain is valueless. [12]

In 1861, English philosopher and economist John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) published one of his most famous essays, Utilitarianism, which was written to support the value of Bentham’s moral theories. The general argument of Mill’s work proposed that morality brings about the best state of a situation, and that the best state of affairs is the one with the largest amount of happiness for the majority of people. Mill also defined happiness as the supremacy of pleasure over pain; however, unlike Bentham, Mill recognised that pleasure can vary in quality. Whereas Bentham saw simple-minded and sensual pleasures, such as drinking alcohol or eating luxurious foods as just as good as complex and sophisticated pleasures, such as listening to classical music or reading a piece of literature, [13] Mill argued that:

‘the pleasures that are rooted in one’s higher faculties should be weighted more heavily than baser pleasures.’

[14] Mill’s version of pleasure also links back to the tradition of Aristotle’s virtue ethics, as he stated that leading a virtuous life should be counted as part of a person’s happiness. [15]

Ultimately, ‘happiness’, at least from a political viewpoint, took its deepest roots in the New World. Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) asserted that:

‘The care of human life and happiness and not their destruction is the first and only legitimate object of good government.’ [16]

He believed that a good government was one that promoted its people’s happiness by securing their rights.

First Printed Version of the Declaration of Independence, 1776, image from http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/creating-the-united-states/interactives/declaration-of-independence/pursuit/enlarge5.html

‘Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness’, the three ‘unalienable rights’ is the phrase most often quoted from the 1776 American Declaration of Independence. Today, Americans translate ‘the pursuit of happiness’ as a right to follow ones dreams and chase after whatever makes you subjectively happy. [17] However, Professor James R. Rogers from Texas A&M University argues that happiness in the public discourse of the late eighteenth-century did not simply refer to an emotional state. Instead, it meant a person’s wealth or well-being. [18] It included the right to meet ‘physical needs’, but it also encompassed an important religious and moral aspect. The Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 confirmed that:

‘the happiness of a people and the good order and preservation of civil government essentially depended upon piety, religion and morality, and… these cannot be generally diffused through a community but by the institution of the public worship of God and of public instructions in piety, religion and morality.’ [19]

Statements like these can be found in many documents of the time. Essentially, ‘happiness’ in the Declaration should be understood as a virtuous happiness, again similar to Aristotle’s ‘Eudaimonia’. Although the ‘pursuit of happiness’ includes a right to material things, it goes beyond that to include a person’s moral condition. [20]

After searching for the philosophy of happiness in twentieth-century Britain, I came across Bertrand Russell’s (1872-1970) The Conquest of Happiness, published in 1930. To my surprise, I found his beliefs on happiness rather modern, and similar to the sort of ideas about happiness you can read about in self-help books today. Nevertheless, I found his work inspiring. Russell wrote this book to ‘suggest a cure’ for the day-to-day unhappiness that most people suffer from in civilised countries. [21]

The key concept of happiness that I took away from Russell’s book was to stop worrying:

‘When you have looked for some time steadily at the worst possibility and have said to yourself with real conviction, “Well, after all, that would not matter so very much,’ you will find that your worry diminishes to a quite extraordinary extent.’ [22]

This also means to stop worrying about what other people think of you, since most people will not think about you anywhere near as much as you think [23], essentially suggesting that people overestimate other negative people’s feelings about them.

With around two thousand self-help books being published every year, it can be argued that happiness is more central to modern-day society than any other time in history. [24]

However, as well as aiming to achieve happiness, there is now a huge emphasis on how to reduce symptoms which prevent happiness, such as anxiety and depression. According to the Huffington Post, around 350,000,000 people around the world are affected by some form of depression. These extortionate statistics has led to the creation of organisations such as Action For Happiness, whose aim is to reduce misery in people’s lives, and encourage people to create more happiness and less unhappiness in the world.

Russian writer Leo Tolstoy (1838-1910) once said:

“If you want to be happy, be.” [25]

The idea that we can simply choose to be happy, regardless of certain aspects of our life that we want to change, is also a prevalent idea today. The best-selling song of 2014, Pharrell Williams’ Happy promotes this idea:

‘Because I’m happy, clap along if you feel like a room without a roof.’ [26]

When asked what these lyrics meant, Williams stated that happiness has no limits and can be achieved by everyone.

Pharrell Williams’ reply. Image from https://twitter.com/Pharrell/status/431011318737698816?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw

Finally, the idea that everyone can achieve happiness has been a topic talked about by Sam Berns. Berns suffered from Progeria and helped raise awareness of this disease. He died one year after appearing in a TEDx Talks video called ‘My philosophy for a happy life’ at the age of seventeen in 2014. In this inspiring video, Berns shares his four key concepts that help him lead a happy life.

1) Overcome obstacles that prevent happiness.

2) Instead of focussing on what you can’t do, focus on what you can do.

3) Surround yourself with people who bring positive energy into your life.

4) Don’t waste energy on feeling bad for yourself.

Overall, it appear that there is no such thing as one concept of ‘happiness.’ From classical antiquity all the way through to present day, the idea of what happiness means culturally and philosophically has developed, and will most likely continue to change in the future.

![“Stark authority was pitted against the subjects' [participants'] strongest moral imperatives against hurting others, and, with the subjects' [participants'] ears ringing with the screams of the victims, authority won more often than not.”](http://teachingblogs.history.qmul.ac.uk/hst6347/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2016/02/Milgram-Experiment-300x206.jpg)