What follows is the text of the paper I gave the 20 June 2017 at the International Conference «Fears and Angers. Historical and Contemporary Perspectives», Queen Mary University, 19-20 June 2017.

Probably Federico Fellini’s Oscar-winning movie, Amarcord, released in 1973, perfectly defines what was supposed to be the, as William Reddy would say, «emotional regime» of fascism. Enthusiasm, faith, happiness, and veneration for the Chief were the dominant public feelings endorsed by fascism. But, despite the public ceremonies being widely, and often sincerely, officiated by Italian people, fascism largely derived consensus from violence and intimidation.

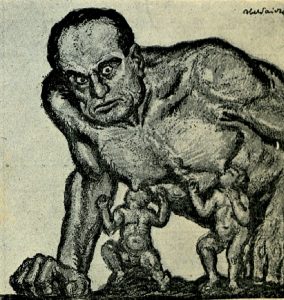

Giacomo Manzù, Black Brigadist, 1943

The annihilation of life produced by fascism is described by Carlo Emilio Gadda in the first lines of his Eros e Priapo. That is the anti-fascist satire, written between 1944 and 1945, through which I would like to address the struggle of fear and anger in this crucial period of Italian history. Gadda writes:

The bribery association that for over twenty years could steal and humiliate and rape Italy, and finally throw it in the very ruin and abyss in which God himself is afraid to look, it depicted as political activity the disruption and erasure of life. […] Collective awareness was concealed in a hidden, invisible lagoon of history, beyond hate and dullness, and belonged to the refugees, the persecuted, the prisoners, the humiliated, the children of deportees and executed to death.

Gadda gives voice to the unspoken emotional suffering of at least a section of the population. He seems to individuate an «emotional refuge» (Reddy again), where the assumption of the existence of fear is already an act of objection. Fear creates a link among the persecuted; it makes recognisable and nameable the discomfort about the material and emotional constraints imposed by fascism. Fear establishes bonds for the formation of, we might say adapting Barbara Rosenwein’s concept, «emotional communities» that organise a first, spontaneous nucleus of resistance against fascism, and often express themselves through literature and art.

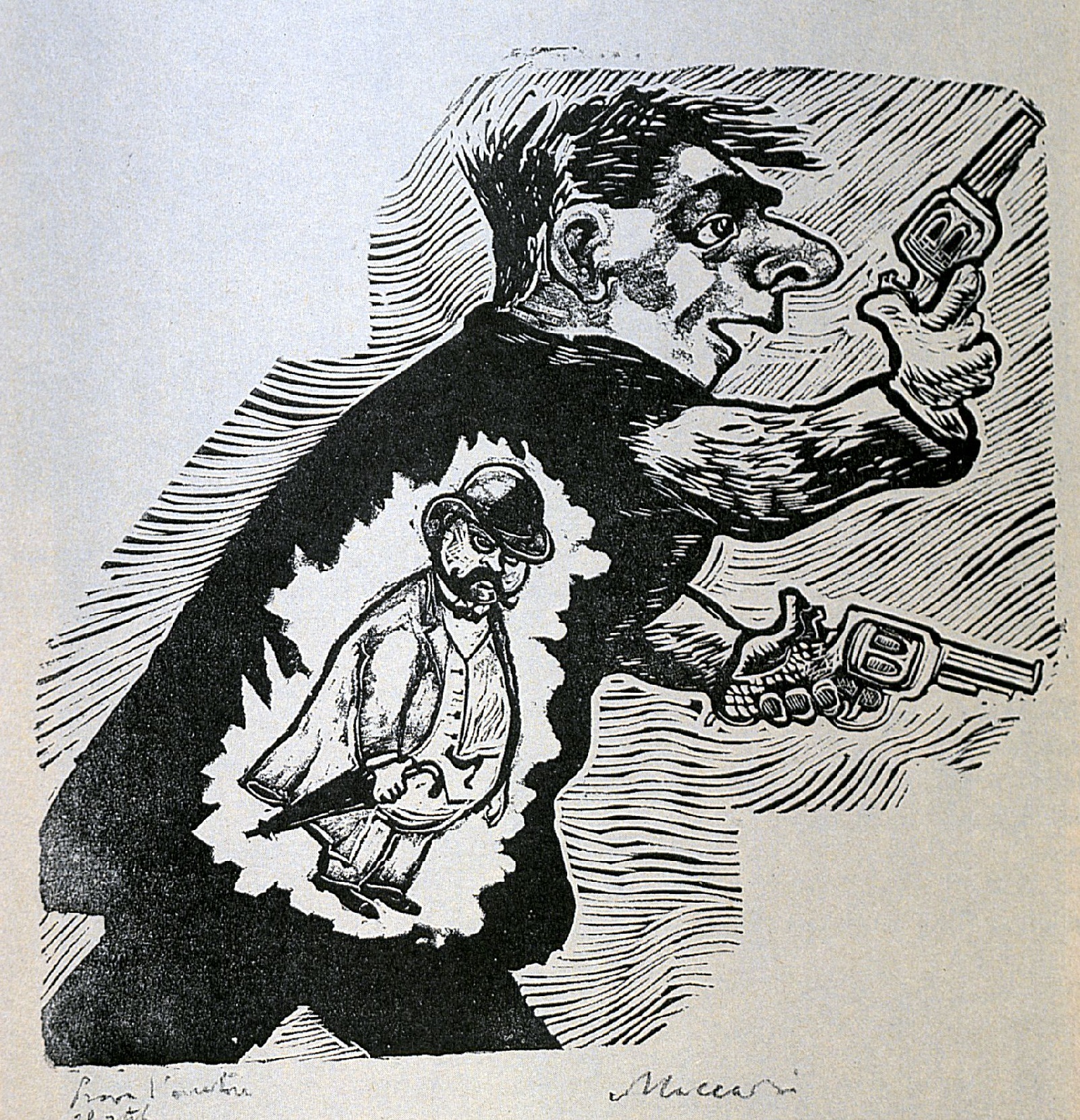

Mino Maccari, Don’t Look Outside for What is Inside, 1934

Renato Guttuso, Countryside Execution, 1938-1939

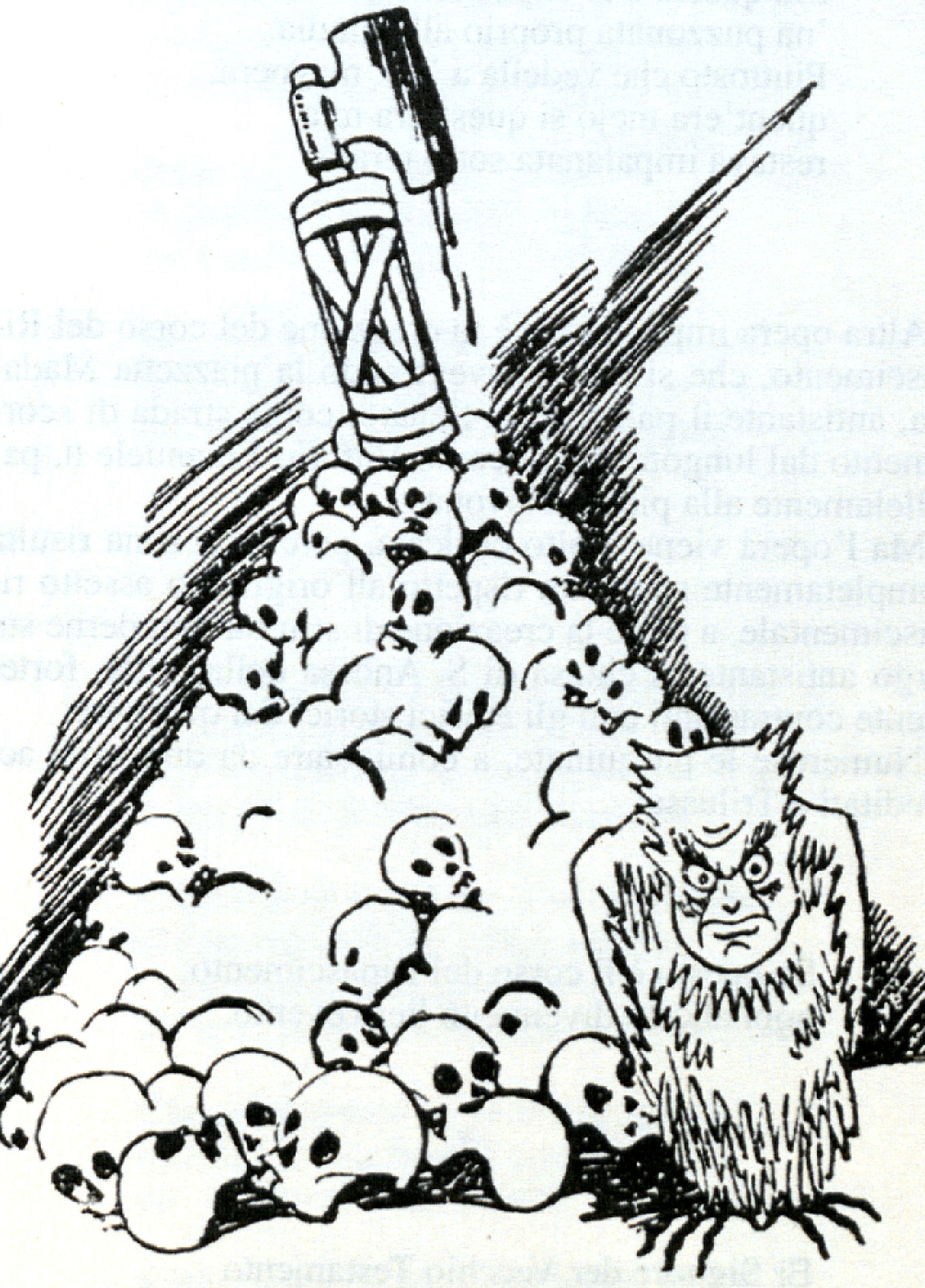

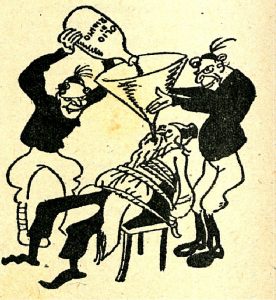

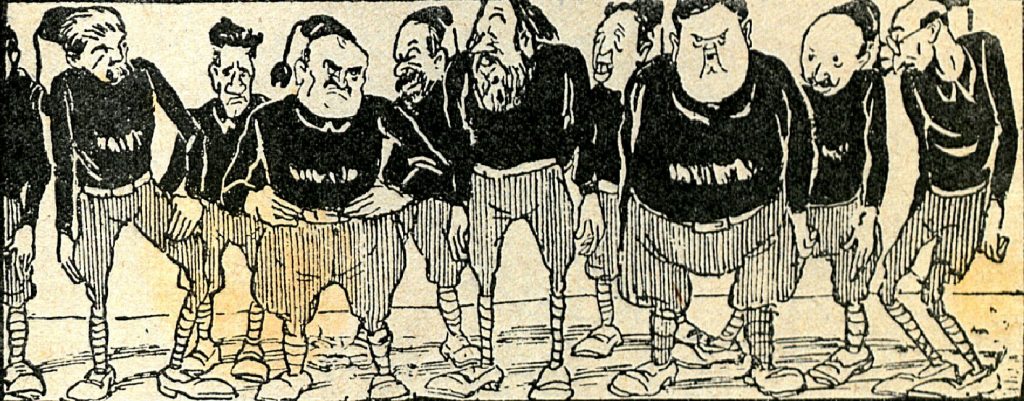

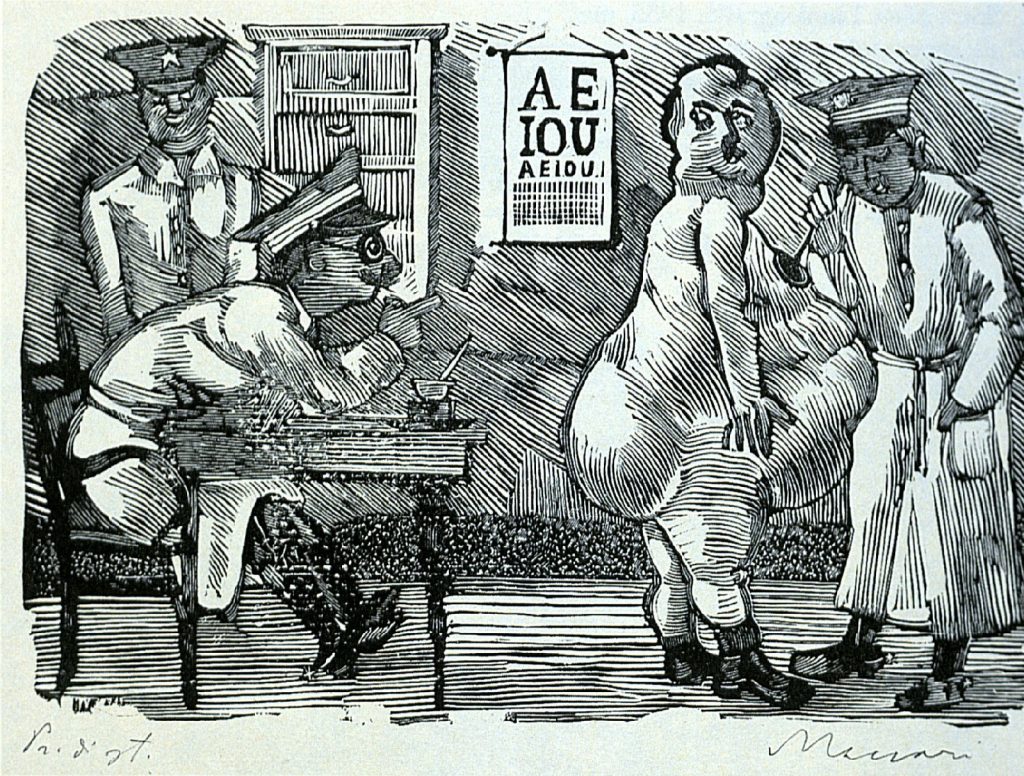

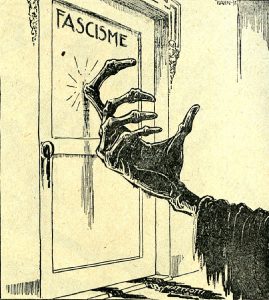

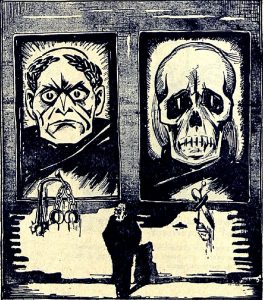

Though, fear is seldom alone within the practices of these emotional communities; it is quite often conjoint with anger, such as in a number of caricatures that circulated during fascism. The style of caricature addresses aggressively the scary and violent aspects of fascism, angrily uncovering them.

Chancel, The Empire and the Emperor, «Becco Giallo», n. 6

Chancel, Fascism Penetrated in People’s Soul, «Becco Giallo», n. 58

I argue that the overturning of fear into anger is the very psychological move that made the birth of oppositional communities possible.

Fear and anger, distress and aggression are entangled within Gadda’s Eros e Priapo. Anger is the device that enables fear to become productive, changing the passivity of fear into an invective. Anger achieves consistency in Gadda’s hard-hitting style, in the violent, emphatic, superlative language of Eors e Priapo, which is written, Gadda himself says, with «clear-headed rage». Anger becomes visible in Gadda’s writing based on deformation, exaggeration, hyperbolic descriptions of physical and behavioural traits.

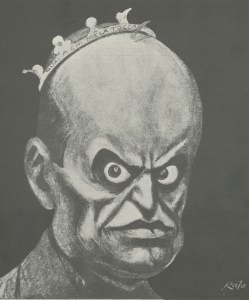

Gadda creates a massive caricature of fascist Italy, applying deformation on two main levels. First, he addresses the body of Mussolini, who is represented as bestial and lustful. Second, he addresses the social body, whose deformed behaviour and abnormal physiology reveal the psychological distortions implied in fascism.

Mussolini established a strong emotional bond with people, mainly through his renowned public speeches. In his performances, he created the illusion of a personal, intimate relationship between the leader and each Italian citizen. Mussolini, Gadda says, «magnifies the Ego through the voice. The voice is a powerful sexual enticement. It turns the political speech into a sensual advance for dummies».

Gadda’s first caricature of the dictator encompasses both his verbal and gestural rhetoric. The aggressive and emphatic words Mussolini pronounces, the theatrical exaggeration of his gestures, inherently misshapes his body and posture. The «formulas and utterances» are associated with «grimaces and digital conjunctions». The violent words produce «the grunts, the Priapus-like jumps, the wide-opened eyes, the arrogant raising of the face», and the exhibition of «the dictator-shaped chin, the sticking out, prolapsed, big belted belly», and the «huge, clumsy, unwanted bottom».

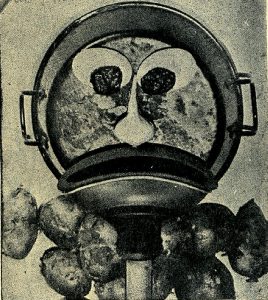

Akar, Surrealist Mussolini

In his speeches, Mussolini is performing the feelings that build fascist emotional regime. Gadda’s text, I argue, mirrors this performance, and displays a counter-performance, that is, a violent monologue in which the refrains and stereotypes of Mussolini’s language are mocked. In Eros e Priapo Gadda creates a character – the one who speaks in the text at the first person – who, as Mussolini, vigorously addresses the Italian people. The speaker himself is a caricature of Mussolini, and this caricature is then refracted across the text: Mussolini is continuously described or evoked through distorted, hyperbolic, degrading images. He has the «head of donkey and tail of pig», he acts with «the ease of an orangutan», showing «the two big bananas bunches of the two hands, the ten fat fingers hanging down on his hips, and held by two short little arms».

Abel Faivre, Capitol Hill She-Wolf, «Codino Rosso», 1924

The image of Mussolini was spread obsessively through all kind of media. Particularly, the reproduction of his portrait strengthened the emotional and intimate relationship with citizens.

Women, Gadda states, could fall in love, and even make love, with Mussolini’s portrait. And Gadda overwrites this ubiquitous portrait.

It takes a rather small stylistic increase to make a caricature out of Mussolini’s image as a manly, energetic reaping farmer:

He was there, big-headed, with a farmer hat on the provolone-like head, there, there, over the tractor, with the naked chest out, exhibiting what he could from the waist up: a couple of scant hair around the nipples: two bad, mediocre nipples, that none would have licked.

The figure of Mussolini, his body, his gestures and above all his head, were the favourite target of caricaturists.

Rata Langa (Gabriele Galantara), HIM, «L’Asino», 21, 1924

Gadda explicitly refers to the humoristic journals that «depicted in caricature the bad face and bad nose and bad mouth, and I won’t say the bad hair, that he hadn’t». References to this production confirm both the visual models of Gadda’s style, and the belonging of his text to the emotional communities that were elaborating fear through anger.

Girus, All Fascists are Good-Looking, «Il Monocolo»

Gadda encompasses the entire Italian society in his greed for deformation. Any single fascist becomes a reproduction, and an extension, of Mussolini’s caricature:

I mention the imitations and useless repetitions of the Priapus-like aggression and frog-like exhibition, and the dictating bray and posture of the Supreme Donkey. Each of them whished, together with the Priapus-like mouth, the squared jaws of the Rotten Maccherone.

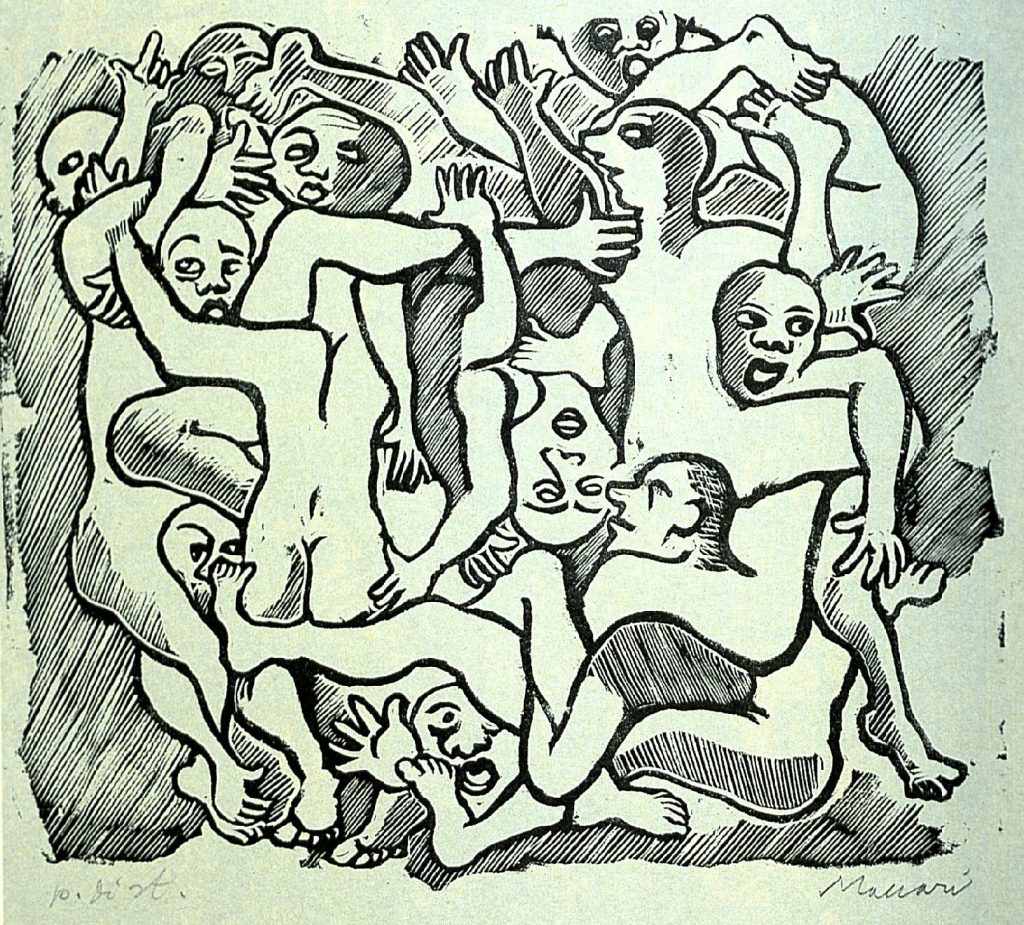

In Gadda’s view, the figure of Mussolini is the fulcrum of fascist power also because his body is the object of desire for the mesmerised body of society. The Italian population was excited by an erotic flow, an emotional tension crossing private and public life. Mussolini was both the source and the target of this tension: all women wanted to be possessed by him; all men wanted to possess his erotic power. As composed of inebriated bacchantes, the mass invokes the leader, who promises his transfigured body: «the mouth as a labial sucker, resembling a sudden penis, and the protruding belly, and the silver knife, that is, phallus moving towards them and almost offering itself to them».

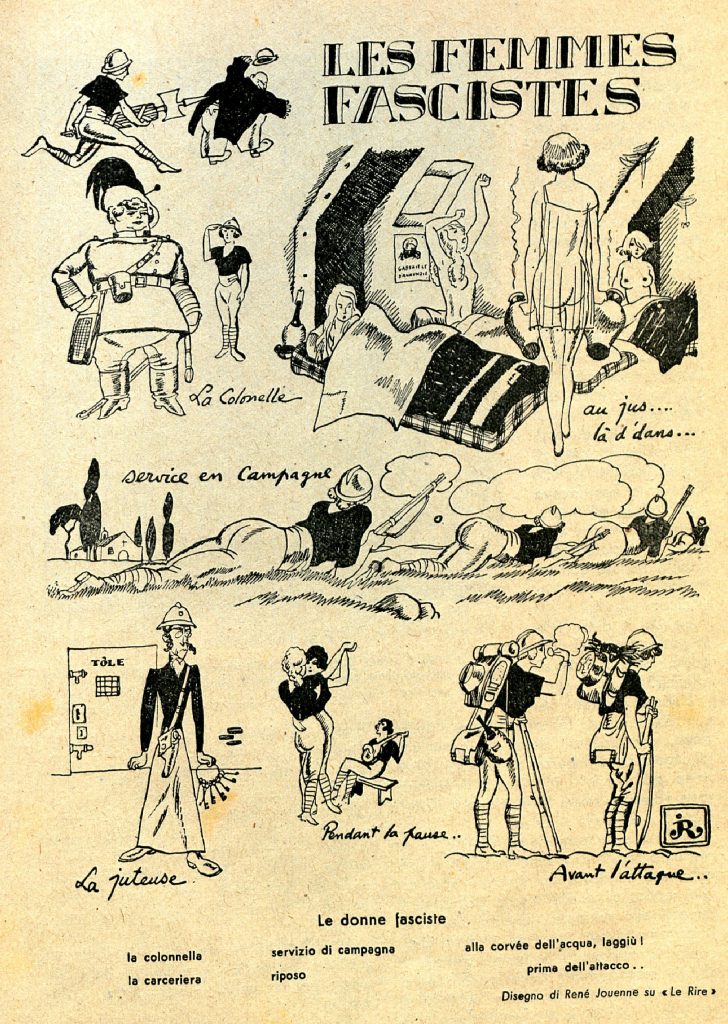

Mino Maccari, Dux, 1943

Fascism is condensed by Gadda in an obscene satirical image: Mussolini presented himself as a giant phallus, to be received by the mind-vaginas of the population. Hence, Eros is the hidden, deeply emotional explanation of fascism. Coherently, Gadda blames Italian women to have been the cornerstone of the regime’s solidity. This is the point where Gadda’s anger reaches its peak, and becomes hardly manageable, above all because it is translated into a violent, often unbearable misogyny. According to Gadda, fascism offers to women the ideal model of virility they are looking for: a violent, arrogant, oppressive man, never tempted by doubts or critical hesitations. Women are satirised in their hysterical participation in public manifestations, in their deep emotional and physical attachment to Mussolini’s figure.

Down in the courtyard here a bunch of duck-like Theresas: they started to wiggle around their hips and bottoms, all around and around with their beaks wide open and the tongues and throats singing the foolish feminine song of human daze and stupidity.

Confirming the ancient, stereotypical association between women and uncontrolled passions, Gadda argues that women brought emotions within the public space, thus endorsing the irrationality of fascism. Women’s behaviour, triggered by desire, contributed to the defeat of reason, legitimated the violence entailed in the triumph of Eros, and enabled the reproduction of fascist emotional regime.

Jouenne, Fascist Women, «Le Rire»

Considering the almost obsessive stress Gadda puts on sex and desire, we could argue that the emotion leading to the overwhelming anger expressed in female portraits is not just fear of the explicit violence of fascism. Fear has a more complex layering in Eros e Priapo. Gadda’s misogyny can be interpreted as the fear of and anger against the sexualisation of public life. Gadda is scared by the strict normative celebration of heterosexuality performed by fascist culture. The model of masculinity imposed by the regime corners his intellectual and likely sexual difference. In fact, in representing himself as the hero of Logos against Eros, Gadda presumably aims at covertly rejecting the apparently unquestionable heterosexual masculinity. In this attempt, he strikes back representing the sexual regime of fascism as perverse, as based on unrestrained lubido, which results in an entire society passively succumbing under the manly control of the Chief. The fear for the political use of Eros is overturned into anger against everyone who made themselves a passive instrument of the dominant normativity.

Denouncing the passivity of society, represented as female, Gadda is, maybe unwillingly, denouncing also his own passivity, the fact that he was unable to state his political, and sexual, diversity. Of course, this denouncement is still sexist, and largely reproduces the phallogocentric discourse of fascism.

The emotionally overloaded discourse of Gadda is still affected by the pressure of the dominant emotional regime, which Gadda is trying to deconstruct through anger. Gadda remains trapped in this action of deconstruction because he is existentially involved in the experiences he is trying to describe and criticise.

Maccari, A Man and his Ideas, «Il Selvaggio», 56, 15 May 1937

This is why deformation falls also upon him: his critical spirit, he says, his reluctance to enthusiasm and consensus, attracted the hostility of patriotic women. Gossiping about him, these patriotic women depict him as a «vile and gross creature, mentally impaired vase of stupidity, psychic abnormal, owl generated by the Night, six-fingered and four-horned monster with a flat beak».

Unquestionably, this is a self-caricature. Of course, in exhibiting the hostility coming from patriotic women, Gadda is bold to try and detach himself from the fascist community. Gadda, who for years has stayed quite ambiguously in the «grey zone» of non-supporters and non-opponents, is trying to gain credit as anti-fascist.

Still, such a violently misshapen portrait cannot be isolated from the system of meanings created by the gallery of caricatures addressing Mussolini and his Italy. Deforming his own figure, Gadda is revealing his involvement in the emotional knot he is trying to unravel. Despite his claim of writing a critical, clear-minded analysis of fascism, Gadda describes his report as a «psychological testimony directly impressed in my soul».

The misshapen profile of the writer emerging from his writing both reveals his fear and applies to himself the anger through which fear is being elaborated.

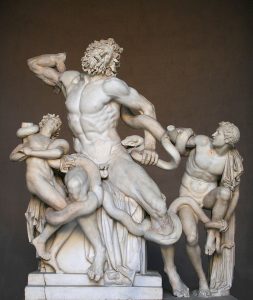

The unbearable harshness and emotional ambiguity of Gadda’s caricatures are connected to his intention to write, as he says, a historiography of the unspoken, that addresses not the visible facts of official history, but the invisible, deep events concerning the mind and body. Gadda claims he wants to write about «the obscure ways and processes of existence related to the zone of the unconscious, those animal and almost bestial drives which Plato collocated in the abdominal pack, that is the vase of the entrails».

Maccari, The Bourgeois, «Il Selvaggio», 10, 31 December 1935

This approach would allow him to give an «overall image of life, not an arbitrary abstraction of a few themes from the general biological context». The exploration of the biological roots of historical events implies facing the dirty and irrational movements of the human mind: «mistakes, madness, moral and intellectual evil, excitement and frantic agitation, public and private unseemliness».

The intention to challenge the dark side of reality partly explains the often intolerable violence of the text. Deformation, exaggeration, hyperbole, insistence on the most degrading bodily functions, must be considered the stylistic tools that give access to the unconscious, and to a reliable history of intimacy.

Indeed, deformation of lines and shapes is traditionally associated with the expression of emotions. «Excitement and frantic agitation», Gadda’s words, was exactly what Aby Warburg was looking for in his research about what he called pathosformeln, that is, artistic forms conveying extreme feelings and passions. Art history is crossed by recurring images in which artists captured movements that reveal states of mind and inner feelings.

Laocoön and His Sons, Vatican Museums

Looking at these kinds of images, Warburg recognised hints of deep, radical, archaic emotional experiences. Interpreting Warburg’s work, the French art historian Georges Didi-Huberman argued that the moving shapes and figures in art don’t just represent emotions, they embody emotions, contain a psychic energy that is re-enacted when these figures reappear. It is like an emotional flow crossing history and making itself visible through the deformation of lines. «Curve is too emotional», stated Mondrian, thus endorsing the idea that misshapen, deformed figures can be used to understand emotional historical contexts. Caricature, in particular, both verbal and visual, can reveal the conflicts agitating the emotional regimes, can track the existence of emotional refuges, and visualise the suffering of minority emotional communities.

Maccari, Collectivism, «Il Selvaggio», 6-7, 15 May 1934

Gadda’s text disrupts the emotional regime performed by fascism by making visible the fear underneath. Fear, mainly associated with death, crosses this literary work from the very beginning to the very end. Death, and particularly the violent murder of opponents, seems to inhabit the unconscious of fascism, as a number of caricatures from the period impressively point out. Caricatures visualised the phantom of death hovering over fascism.

Hahn Jr, Someone is Knocking, «Notenkraker»

Hahn Jr, Tiranny or Death, «Notenkrakerr»

The deathly inclination of fascism becomes overwhelming during the pro-war campaigns. Society seems to quiver with enthusiasm for the imminent bloodbaths. Gadda creates a parallel between the fear he experienced serving in WWI and the fear he experienced in the war-acclaiming fascist society. He compares «that anxieties, that vigils, that sacred hopes, that prayers, that pain shaping the texture of souls, of my soul, in the remote years» and the «desperate certainty of ruin, and the breath of darkness, which disrupted lives, and my life, in the present years».

From its origin, fascism worshipped death. The very first image of the book released by the regime in 1932 to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the conquest of power displays the monumental grave of a «fascist martyr».

Monument for the Fascist Martyrs

The last lines of Eros e Priapo allude to the same fascist celebration of martyrs. In these ceremonies, fascists used to call the name of the dead, then shout the word present, to say: alive in memory. But after this celebration, Gadda says, the comrades disappear and the corpse «remained by himself in his coffin and ground. The grim, vile echo of that present was not faded yet, and already they sat at the table, with the bad face on their maccheroni».

Once deceptive enthusiasm is deconstructed through the lens of anger, what is left of fascism is the loneliness of this corpse, irradiating the bare fear that is one of the crucial emotions of the short, but scary, Twentieth Century.

My brother suggested I may like this blog. He used to be totally right. This put up truly made my day. You cann’t consider simply how much time I had spent for this information! Thank you!

전신스타킹

Your blog is a true hidden gem on the internet. Your thoughtful analysis and in-depth commentary set you apart from the crowd. Keep up the excellent work!

Hello! This is kind of off topic but I need some advice from an established blog. Is it hard to set up your own blog? I’m not very techincal but I can figure things out pretty fast. I’m thinking about creating my own but I’m not sure where to begin. Do you have any ideas or suggestions? Cheers

I haven’t checked in here for a while since I thought it was getting boring, but the last several posts are great quality so I guess I’ll add you back to my everyday bloglist. You deserve it my friend 🙂

Definitely believe that which you said. Your favorite reason seemed to be on the web the simplest thing to be aware of. I say to you, I definitely get irked while people consider worries that they plainly do not know about. You managed to hit the nail upon the top and defined out the whole thing without having side-effects , people can take a signal. Will likely be back to get more. Thanks

https://new-version.download/