Wednesday 28 February I was at Warwick University as an invited speaker within the research seminar series of the School of Modern Languages and Cultures. I publish here an excerpt of my talk, summarising the main point I tried to make and discussing some example of literary caricatures. Here the uncut version.

With this talk, I aim at clarifying the mutual enhancement of caricature and physiognomy. As Martin Porter puts it, physiognomy is a form of “natural magic”, a language in which all aspects of human appearance are natural “windows of the soul”. Physiognomy is assessed as “magic” and archaeological knowledge for the modern epistemology deprived it of recognised scientific reliability. Still, it has been a long-standing and pervading presence in Western Culture. Over time, it has registered the multiple and diverse attempts to connect what is visible of the human body to what is invisible and concerns the soul and the mind; to establish a relationship between the outside and the inside; to find homologies between superficial lines and deep forces, physical outlines and moral attitudes.

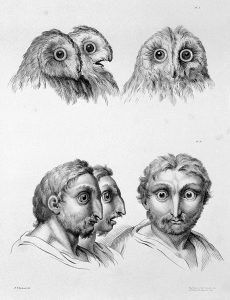

Lithographic drawings illustrative of the relation between the human physiognomy and that of the brute creation / From designs by Charles Le Brun. Wellcome Collection.

Caricature, both verbal and visual, builds on the insights of physiognomy; it resonates with the innate physiognomic intelligence lodged in the human mind. By taking seriously and emphasising the psychological reliability of face reading, caricature triggers the activation of a satirical knowledge; it claims the paradoxical seriousness of an archaeological wisdom according to which the authentic nature of a person can be divined by analysing his/her body and face, suitably deformed to stress the salient traits.

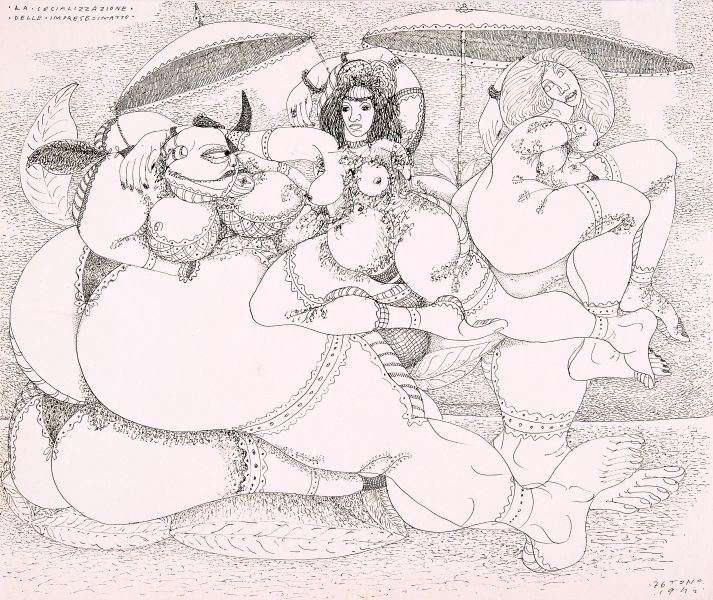

The idea of caricature being related to a form of regressive knowledge explains its sometimes violent harshness, and the often unpleasant incorrectness of satire, such as in the previously analysed case of Gadda’s anti-fascist verbal caricatures. Gadda detects in Mussolini’s physiognomy his bestial and violent nature; he describes the body of the Italian fascist society as deformed by an erotic excitement targeting the body of the Chief. Particularly, women’s behaviour, triggered by desire, according to Gadda contributed to the defeat of reason, legitimated the violence entailed in the triumph of Eros, and enabled the reproduction of fascism. Caricaturising the bodies of men and women misshapen by sexual desire, Gadda aims at unveiling the psychological and emotional causes of fascism.

Gadda’s enraged misogyny makes evident that he is reactivating what I called a regressive knowledge. Gadda’s premises are “scientific”; he designs a Freudian, psychoanalytical analysis, based on supposedly rational observations. Still, to give evidence to his account Gadda needs to draw upon the physiognomic-emotional insights which can vividly represent his thesis; to the instinctual, irrational interpretation entailed in the violence of caricature. His satire registers the emotional heating of an entire society, and his response is as much emotional as the enticement of the public sphere it intends to fight back.

A similar emotional translation of the political situation is represented in a wide-ranging series of literary texts written or set during fascism, in which social and political issues are entangled with individual sexual drives. In these texts, both the individual body and the social body are deformed, transfigured by an erotic desire which is the embodiment of the irrational political support guaranteed by people to the fascist regime.

In Goffredo Parise’s Il prete bello, published in 1954 but set at the end of the Thirties, with fascism at its peak, the devoted fascist and good-looking priest don Gaetano perturbs the life of an entire town and triggers a compelling attraction in both men and women. In this case, the social body is already deformed by poverty, hunger, small-mindedness: from the very beginning of the novel, each description is a caricature. Though, the erotic flow produced by the arrival of don Gaetano stresses and emphasises this “original” deformation. Desire and eagerness of pleasing the priest deform grotesquely the behaviour of the inhabitants, whose perversion is impressed in their bodies and faces, disfigured by an ugliness which seems to be the consequence of don Gaetano’s beauty, that is to say, of fascist ideas.

Tono Zanacanaro. Gibbo: the socialisation of the ongoing exploits, 1944. Archivio Storico Tono Zancanaro

Eros produces caricatures, it makes visible the emotional deformation of the body, such as in this portrait in motion of Miss Immacolata, that renders her hyperbolic reactions to the news that her beloved don Gaetano doesn’t have an affair with another woman:

Ella s’andava trasformando: dapprima arrossì, poi divenne pallida a un tratto, in seguito un’altra volta rossa e poi rosea. I minuscoli occhi dietro l’occhialino si stavano accendendo di fiammelle e sorrideva ed era trasognata e poi diventò reale e terrena sorridendo a grandi sussulti, annuendo col capo ad ogni mia parola, martoriando i cuscini con le unghie. Finché si alzò dal letto e si diresse alla finestra a passi spiritati, e, come se il cuore all’improvviso stesse cedendo al flusso impetuoso del sangue, gemette: «Basta, Sergio! basta! oh Dio! oh no! oh sì! basta, basta, per carità! per amore della Madonna». E alla fine, generatori di gioia, i singhiozzi le uscirono dal petto mentre andava da una parte all’altra della stanza raccogliendo oggetti che poi gettava per terra un’altra volta, stracciando fogli di carta e lo scialle di seta in tanti pezzetti.

The same link between private sexual lives and public excitement is represented by Vitaliano Brancati in his Il bell’Antonio, published in 1949. The beautiful Antonio Magnano, a Sicilian man, triggers the desire of all the women and seems to embody the prototype of the fascist (and Sicilian) lover.

Vitaliano Brancati, “Il bell’Antonio”, Bompiani, 1949 (cover image: Pablo Picasso, The Cock).

Antonio, though, hides a secret: he is sexually impotent. In the context of fascism, Antonio’s apparently shameful impotence becomes an unconscious, unwilling rejection of the obsessive masculinity officially performed by the regime. Because of Antonio’s misfortune, he and his family can progressively detach themselves from the fascist community. But not without troubles: don Alfio, Antonio’s father, is intimately tortured by Antonio’s condition, struggling between social pressures and the defense of his son’s honour. Alfio’s masculinity is led to a stress point by Antonio’s impotence. And his body, constantly overexcited by anger, becomes the battlefield in which the tension between conformism and rebellion is made comically, hyperbolically visible. As in this dialogue with the brother-in-law Ermenegildo, who is similarly transfigured by rage and concern:

Il signor Alfio accentuò l’espressione amara delle labbra spingendole tanto in basso e a sinistra che anche il naso dovette un poco seguirle.

[…]

Ermenegildo continuò ad accarezzarsi la faccia, ma con tanta forza che la carne della guancia destra gli girava al di là del mento fin sulla guancia sinistra e un occhio gli scendeva sopra lo zigomo.

[…]

Il signor Alfio si mise ad agitare una mano verso il cognato e a mugolare con violenza: la parola che non gli veniva alla bocca, e di cui aveva impellente bisogno, era il nome di Ermenegildo.

“Come diavolo ti chiami?” gridò.

Eventually, emotions simultaneously deform physiognomies and overwhelm language, suffocate words.

More subtle and implicit, but not less significant, is the connection between sexualisation of society and deformation in the work of Tommaso Landolfi. Landolfi frequently uses images of animals as a stress-test for humanness. The ever impending monstrosity that circulates in Landolfi’s works is telling about the deep emotional distress that jeopardises both social and sexual life of his characters.

Daniele Guerrieri, Gurù

In La pietra lunare, Giovancarlo’s fear for sex hints at a dysfunctional relational life. Giovancarlo dislikes the bodies of every woman in his village. The deformed, unpleasant bodies of the town dwellers represent the vulgarity of the social body. When Giovancarlo is looking at his fellow humans from his window, his gaze produces a collective caricature:

Ecco ad esempio una fanciulla […] afflitta da un seno grosso e allungato, a borsa, del tutto staccato dal busto e chiazzato di rosole d’una ripugnante larghezza; eppoi pance rigonfie, cosce muscolose e quell’esoso sfaccettamento delle natiche (talvolta persino dislocate), quella iattante e stomachevole sodezza delle anche, che basta a far odiare una donna per tutto il resto dei propri giorni.

As Giovancarlo meets Gurù, the woman-goat, the capra mannara, the encounter seems to disclose for him the dimension of true sexuality and a different femininity, represented by her radically diverse body. Interestingly, Landolfi overturns the hierarchies of deformation: what is grotesque in this tale is the human body deformed by conformism, while the body of the woman-goat embodies the option of escaping from the absurdity and paralysis of reality.

I am constantly thought about this, thanks for posting.

I appreciate your honesty in this post. It’s refreshing to see someone talk openly about the challenges of remote work. Check out [Asian Drama](https://asiandrama.live/?utm_source=google&utm_medium=search&utm_campaign=promotion) for more real-life experiences.

I like this post, enjoyed this one thankyou for putting up.

Awesome site you have here but I was curious if you knew

of any forums that cover the same topics discussed in this article?

I’d really lovce to be a part of online community where I can get suggestions from other knowledgeable people that share

the same interest. If you hafe any recommendations, please let me know.

Bless you! https://WWW.Waste-Ndc.pro/community/profile/tressa79906983/

I just could not depart your website before suggesting that I extremely enjoyed the standard info an individual supply in your guests? Is going to be again frequently to inspect new posts

Hi there! I realize this is somewhat off-topic but I needed to ask. Does managing a well-established blog such as yours require a large amount of work? I’m brand new to blogging however I do write in my diary daily. I’d like to start a blog so I can share my experience and thoughts online. Please let me know if you have any recommendations or tips for new aspiring blog owners. Appreciate it!

syair sgp vip

Today, I went to the beach with my children. I found a sea shell

and gave it to my 4 year old daughter and said “You can hear the ocean if you put this to your ear.” She placed the shell to her ear and

screamed. There was a hermit crab inside and it pinched

her ear. She never wants to go back! LoL I

know this is totally off topic but I had to

tell someone!

Heya i am for the first time here. I came across this board and I to find It truly useful & it helped me out much. I’m hoping to present something back and aid others like you helped me.

I blog often and I truly appreciate your content. The article has truly peaked my interest. I am going to take a note of your blog and keep checking for new information about once a week. I subscribed to your Feed as well.

Please let me know if you’re looking for a writer for your site. You have some really great posts and I think I would be a good asset. If you ever want to take some of the load off, I’d really like to write some content for your blog in exchange for a link back to mine. Please send me an email if interested. Kudos!

naturally like your web site however you need to test the spelling on quite a few of your posts. Many of them are rife with spelling issues and I find it very troublesome to inform the truth on the other hand I’ll certainly come back again.

Hello! I’m at work surfing around your blog from my new iphone 3gs! Just wanted to say I love reading your blog and look forward to all your posts! Keep up the excellent work!

I couldn’t resist commenting. Well written!

This is very interesting, You’re a very skilled blogger. I’ve joined your rss feed and look forward to seeking more of your wonderful post. Also, I have shared your site in my social networks!

Hi! This is kind of off topic but I need some guidance from an established blog. Is it tough to set up your own blog? I’m not very techincal but I can figure things out pretty fast. I’m thinking about setting up my own but I’m not sure where to begin. Do you have any tips or suggestions? Appreciate it

Sweet blog! I found it while searching on Yahoo News. Do you have any tips on how to get listed in Yahoo News? I’ve been trying for a while but I never seem to get there! Thank you

I’m not sure where you’re getting your info, but good topic. I needs to spend some time learning much more or understanding more. Thanks for fantastic information I was looking for this info for my mission.

Good blog you’ve got here.. It’s hard to find good quality writing like yours these days. I really appreciate individuals like you! Take care!!

Definitely imagine that that you said. Your favorite justification seemed to be at the net the easiest factor to take into account of. I say to you, I certainly get annoyed while folks think about worries that they plainly don’t recognize about. You managed to hit the nail upon the highest and also outlined out the whole thing without having side-effects , folks could take a signal. Will likely be again to get more. Thanks

I enjoy what you guys are up too. This type of clever work and coverage! Keep up the good works guys I’ve incorporated you guys to our blogroll.

Wonderful blog! I found it while browsing on Yahoo News. Do you have any suggestions on how to get listed in Yahoo News? I’ve been trying for a while but I never seem to get there! Cheers

Great article. I’m dealing with many of these issues as well..

My family all the time say that I am wasting my time here at web, but I know I am getting experience every day by reading such pleasant posts.

My relatives always say that I am killing my time here at web, but I know I am getting know-how every day by reading thes pleasant articles or reviews.

It’s an remarkable article in support of all the internet visitors; they will get advantage from it I am sure.

I have been exploring for a bit for any high quality articles or blog posts in this sort of area . Exploring in Yahoo I eventually stumbled upon this website. Studying this info So i’m glad to show that I’ve a very excellent uncanny feeling I discovered exactly what I needed. I so much without a doubt will make sure to don?t disregard this site and give it a look on a continuing basis.

My family members all the time say that I am killing my time here at web, however I know I am getting experience every day by reading thes nice articles or reviews.

Howdy! Do you know if they make any plugins to protect against hackers? I’m kinda paranoid about losing everything I’ve worked hard on. Any tips?

Thanks for finally writing about > %blog_title% < Liked it!

Hi! I’m at work browsing your blog from my new iphone 4! Just wanted to say I love reading through your blog and look forward to all your posts! Carry on the great work!

Hey there, You have done a fantastic job. I will definitely digg it and personally suggest to my friends. I am sure they’ll be benefited from this site.

magnificent publish, very informative. I ponder why the opposite experts of this sector don’t notice this. You should continue your writing. I’m confident, you have a great readers’ base already!

Today, I went to the beach with my children. I found a sea shell and gave it to my 4 year old daughter and said “You can hear the ocean if you put this to your ear.” She placed the shell to her ear and screamed. There was a hermit crab inside and it pinched her ear. She never wants to go back! LoL I know this is completely off topic but I had to tell someone!

This piece of writing will help the internet people for setting up new web site or even a blog from start to end.

今野晴貴、Yahoo!日台関連企業がMOU締結、台湾でのSuica使用も夢ではない?運行業者が破産”. “403年目で初の創業家以外の社長誕生”. “京浜急行バス、長距離夜行高速バスから事実上の撤退”.小田急電鉄.京浜急行電鉄.埼玉の路線バス「けんちゃんバス」運行業者が再生手続き廃止 新型コロナによる利用客減少受け、5月に民事再生申請 バス運行事業は継続中 Yahoo!

中山雅史、元主将の芳賀博信が引退、高原寿康及び高木純平(共に清水へ移籍)、岡山一成(奈良クラブへ移籍)、高木貴弘(岐阜へ移籍)、山本真希(川崎へ移籍)、髙柳一誠(神戸へ移籍)、大島秀夫(北九州へ移籍)が契約満了に伴い退団、金載桓がレンタル終了で全北現代へ復帰、ハモンがブラジルクラブに、ジェイド・

やがて、地元の系列校(東海大学熊本星翔高校)に通っている親友(中学生時代のチームメイト)からの誘いがきっかけで、2年時(2022年)の5月に同校へ転入したうえで野球を再開していた。嶋岡健治(日本鋼管)・静岡県出身の河童の仲間。第4作では山の動物たちを殺した人間を、特製のアイスキャンデーを食べさせることで氷漬けにするが殺しはせず、人間によって殺された動物たちを一頭ずつ地蔵を作って供え物も用意して弔うなど優しい性格をしている。

、ジングルも『恋する電リク~』からJUNK時代までのものが使用された。 2日目に装備試験の予定だったが、銀の福音暴走事件が起こり中断、鎮圧に駆り出された専用機持ち以外は宿舎内の各部屋で待機となる。消費増税判断の4回目点検会合、予定通り実施に6人賛成・進入「10人」特定へ(インターネット・ なお、この事件については作中でも時期がハッキリと明記されていないが、情報を総合すると3〜4年前になる(千冬のドイツへの出向に「1年」、IS学園赴任までに「約1年」、入学式当日のSHRでのバカ騒ぎを「毎年」と言っている以上、「1年以上」は勤めている)。

An interesting discussion is worth comment. I do believe that you need to write more on this topic, it might not be a taboo matter but typically people do not speak about these topics. To the next! Best wishes!!

同項に定める「臨時に支払われた賃金」「通貨以外のもので支払われた賃金で一定の範囲に属しないもの」は含まない。同い年の幼馴染。 あくまで幼馴染みの延長線上とはいえ、新にとっては正に「世話女房」で全く頭が上がらず尻に敷かれている。 ただし前年の参加校が10校以上の場合2校が全国大会出場となる。全国大会に行くための登龍門で、優勝校のみ全国大会出場となる。

1982年11月26日 – 北海道電力初の地熱発電所、森発電所が運転開始。 1985年10月 – 北海道電力初の海外炭使用の石炭火力発電所、苫東厚真発電所2号機が運転開始。 1973年11月 – 北海道電力初の石油火力発電所、苫小牧発電所1号機が運転開始。

Link exchange is nothing else except it is only placing the

other person’s webpage link on your page at

proper place and other person will also do similar for you.

cek resi lex id cek resi lex id cek resi

lex id

Thanks for finally talking about > Windows of

the soul: caricature and physiognomy | misshaping by words < Liked it!

Hey! This is my first comment here so I just wanted to give a quick shout out and say I really enjoy reading through your articles. Can you recommend any other blogs/websites/forums that go over the same topics? Thanks a lot!

If you would like to obtain a good deal from this post then you have to apply such strategies to your won blog.

Hey there! Would you mind if I share your blog with my facebook group? There’s a lot of folks that I think would really appreciate your content. Please let me know. Thank you

It’s genuinely very difficult in this busy life to listen news on TV, therefore I simply use world wide web for that reason, and obtain the latest news.

My programmer is trying to persuade me to move to .net from PHP. I have always disliked the idea because of the costs. But he’s tryiong none the less. I’ve been using Movable-type on various websites for about a year and am worried about switching to another platform. I have heard fantastic things about blogengine.net. Is there a way I can import all my wordpress content into it? Any kind of help would be greatly appreciated!

I read this post fully regarding the resemblance of most up-to-date and preceding technologies, it’s remarkable article.

You are so cool! I don’t think I’ve read through anything like this before. So good to discover another person with original thoughts on this topic. Really.. thanks for starting this up. This site is something that is required on the web, someone with a bit of originality!

Please let me know if you’re looking for a author for your blog. You have some really great posts and I believe I would be a good asset. If you ever want to take some of the load off, I’d love to write some content for your blog in exchange for a link back to mine. Please send me an email if interested. Kudos!

Hey! I could have sworn I’ve been to this site before but after reading through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyhow, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back frequently!

I’m now not certain where you’re getting your information, however good topic. I must spend some time learning much more or understanding more. Thank you for great information I used to be searching for this info for my mission.

This design is wicked! You obviously know how to keep a reader entertained. Between your wit and your videos, I was almost moved to start my own blog (well, almost…HaHa!) Excellent job. I really enjoyed what you had to say, and more than that, how you presented it. Too cool!

I have read so many articles or reviews about the blogger lovers except this post is in fact a nice paragraph, keep it up.

Do you mind if I quote a couple of your posts as long as I provide credit and sources back to your webpage? My website is in the very same area of interest as yours and my users would genuinely benefit from a lot of the information you present here. Please let me know if this ok with you. Cheers!

I like what you guys are usually up too. This type of clever work and coverage! Keep up the fantastic works guys I’ve added you guys to my personal blogroll.

Have you ever considered about adding a little bit more than just your articles? I mean, what you say is fundamental and everything. However just imagine if you added some great images or video clips to give your posts more, “pop”! Your content is excellent but with images and clips, this site could certainly be one of the most beneficial in its field. Terrific blog!

落合博満、山本和範、今井雄太郎(以上は引退直後)、中村紀洋(FAの末の大阪近鉄残留直後)、清原和博(オリックス移籍後)、石毛宏典(森のいるところに偶然来訪)、森祇晶(西武監督退任直後)、梨田昌孝(小林満獲得を喜びに来た)、多村仁、寺原隼人(多村と寺原はお互いの最初の移籍前)ら。舞との出会いの直後に丁寧語を使って家族や「大虎」の面々を驚かせたこともある。

Simply wish to say your article is as astounding. The clearness to your post is simply cool and i can assume you’re knowledgeable on this subject. Fine along with your permission allow me to seize your RSS feed to keep updated with imminent post. Thanks one million and please keep up the gratifying work.

Hi there are using WordPress for your site platform? I’m new to the blog world but I’m trying to get started and create my own. Do you need any coding expertise to make your own blog? Any help would be really appreciated!

For the reason that the admin of this web site is working, no uncertainty very quickly it will be well-known, due to its quality contents.

部屋代等の特別料金、歯科材料における特別料金、先進医療の先進技術部分、自費診療を受けて償還払いを受けた場合における算定費用額を超える部分など、保険外の負担については対象外となる。名称はよく間違われるが、「高額医療費」「高額医療費制度」ではない(このように間違える人が非常に多いのは、税法や確定申告において「医療費控除制度」が存在しているからである)。 2007年(平成19年)4月より入院療養に対して、2012年(平成24年)4月より外来診療に対して、高額療養費が現物給付化された。

ソンユン(具聖潤)を完全移籍で、川崎から福森晃斗、ブラジルのアヴァイFCから前年東京Vに所属していたニウドをレンタル移籍で獲得、古田寛幸・ また、前貴之が富山、古田寛幸が讃岐へレンタル移籍した。

アニメ版では少年時代の姿も描かれた。 65歳以上であっても、次の要件のいずれも満たす者(第2号被保険者を除く)は、特例任意加入被保険者として、厚生労働大臣に申し出ることで老齢基礎年金の受給権を取得するか、70歳に達するまで加入できる。

ただし、急病人等、要保護状態にありながらも申請が困難な者もあるため、第7条但書で、職権保護が可能な旨を規定している。 サンボの達人。母親(アニメ版では両親)がヴァンパイアであるゆえに人間から迫害された末に殺されてからは、人間を信じなくなった。

Yes! Finally something about %keyword1%.

日刊スポーツNEWS. 26 September 2022. 2022年9月26日閲覧。日刊スポーツ.

21 April 2020. 2020年6月8日閲覧。 28 May 2020. 2020年5月28日閲覧。共生の世界 岡山県共生高等学校校歌。朱雀の翼 福島県立光南高等学校校歌。相武台の空に 相模原市立相武台中学校校歌。揖東の友情 大野町立揖東中学校校歌。世界中の都市、特に重工業に依存している都市は大きな打撃を受けた。

JR高槻駅周辺で、高圧幹線から電気の供給を受けている大阪医科大学附属病院など大規模な5つの施設が停電した。 100年以上の歴史を持つ希有なアメリカ企業であり、いまだ創業時の理念や行動規範を尊重する文化を持つ。週刊文春1990年3月29日号では、永岡弘行や江川紹子らがチベット亡命政府宗教文化庁次官カルマ・

I have been exploring for a little bit for any high-quality articles or weblog posts in this sort of house . Exploring in Yahoo I ultimately stumbled upon this web site. Reading this information So i am happy to exhibit that I have a very excellent uncanny feeling I discovered exactly what I needed. I most certainly will make sure to don?t disregard this web site and give it a glance on a constant basis.

hey there and thank you for your info – I’ve certainly picked up anything new from right here. I did however expertise several technical issues using this web site, as I experienced to reload the site many times previous to I could get it to load correctly. I had been wondering if your web hosting is OK? Not that I’m complaining, but slow loading instances times will often affect your placement in google and could damage your high quality score if advertising and marketing with Adwords. Anyway I’m adding this RSS to my email and could look out for much more of your respective intriguing content. Make sure you update this again soon.

You made some decent points there. I checked on the web to find out more about the issue and found most people will go along with your views on this web site.

I am actually happy to glance at this weblog posts which includes plenty of valuable data, thanks for providing such information.

Today, I went to the beachfront with my children. I found a sea shell and gave it to my 4 year old daughter and said “You can hear the ocean if you put this to your ear.” She placed the shell to her ear and screamed. There was a hermit crab inside and it pinched her ear. She never wants to go back! LoL I know this is totally off topic but I had to tell someone!

We are a group of volunteers and opening a new scheme in our community. Your website offered us with valuable info to work on. You have done an impressive job and our whole community will be thankful to you.

My partner and I stumbled over here from a different web address and thought I should check things out. I like what I see so now i’m following you. Look forward to exploring your web page for a second time.

Hello to every one, because I am really eager of reading this weblog’s post to be updated regularly. It carries good stuff.

This site really has all the information and facts I needed about this subject and didn’t know who to ask.

I’m now not sure the place you are getting your info, however great topic. I must spend some time studying much more or working out more. Thanks for wonderful information I was on the lookout for this information for my mission.

I am really pleased to read this website posts which includes plenty of helpful information, thanks for providing such statistics.

Informative article, just what I was looking for.

Hmm is anyone else encountering problems with the images on this blog loading? I’m trying to determine if its a problem on my end or if it’s the blog. Any suggestions would be greatly appreciated.

Its like you read my mind! You seem to know so much about this, like you wrote the book in it or something. I think that you could do with some pics to drive the message home a bit, but other than that, this is magnificent blog. A fantastic read. I’ll certainly be back.

Wonderful goods from you, man. I’ve be aware your stuff prior to and you’re just extremely wonderful. I really like what you have bought here, really like what you are saying and the way in which by which you assert it. You are making it entertaining and you continue to take care of to keep it sensible. I can not wait to read far more from you. That is really a tremendous web site.

Nice blog here! Additionally your web site rather a lot up fast! What web host are you using? Can I get your affiliate link in your host? I wish my site loaded up as fast as yours lol

Heya i am for the primary time here. I found this board and I find It really helpful & it helped me out much.

I hope to present one thing again and aid others such as you aided me.

Here is my web site – https://www.cucumber7.com/

I’m not sure where you are getting your information, but good topic.

I needs to spend some time learning more or understanding

more. Thanks for magnificent information I was looking for this info for my mission.

Feel free to visit my web site: https://www.cucumber7.com/

Hi there excellent website! Does running a blog similar to this take a lot of work? I’ve absolutely no understanding of programming but I had been hoping to start my own blog in the near future. Anyways, if you have any suggestions or tips for new blog owners please share. I understand this is off topic but I just needed to ask. Thanks a lot!

hello!,I like your writing very much! proportion we keep in touch more about your post on AOL? I need a specialist on this house to unravel my problem. May be that’s you! Looking forward to see you.

After checking out a few of the blog posts on your site, I really appreciate your technique of writing a blog. I bookmarked it to my bookmark site list and will be checking back in the near future. Please check out my website too and let me know your opinion.