Wednesday 28 February I was at Warwick University as an invited speaker within the research seminar series of the School of Modern Languages and Cultures. I publish here an excerpt of my talk, summarising the main point I tried to make and discussing some example of literary caricatures. Here the uncut version.

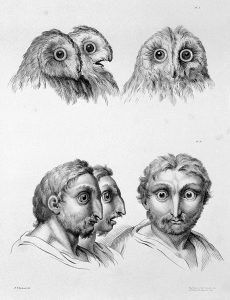

With this talk, I aim at clarifying the mutual enhancement of caricature and physiognomy. As Martin Porter puts it, physiognomy is a form of “natural magic”, a language in which all aspects of human appearance are natural “windows of the soul”. Physiognomy is assessed as “magic” and archaeological knowledge for the modern epistemology deprived it of recognised scientific reliability. Still, it has been a long-standing and pervading presence in Western Culture. Over time, it has registered the multiple and diverse attempts to connect what is visible of the human body to what is invisible and concerns the soul and the mind; to establish a relationship between the outside and the inside; to find homologies between superficial lines and deep forces, physical outlines and moral attitudes.

Lithographic drawings illustrative of the relation between the human physiognomy and that of the brute creation / From designs by Charles Le Brun. Wellcome Collection.