Here are brief descriptions of the papers that will be presented next September 13th at the Mis-Shapings conference.

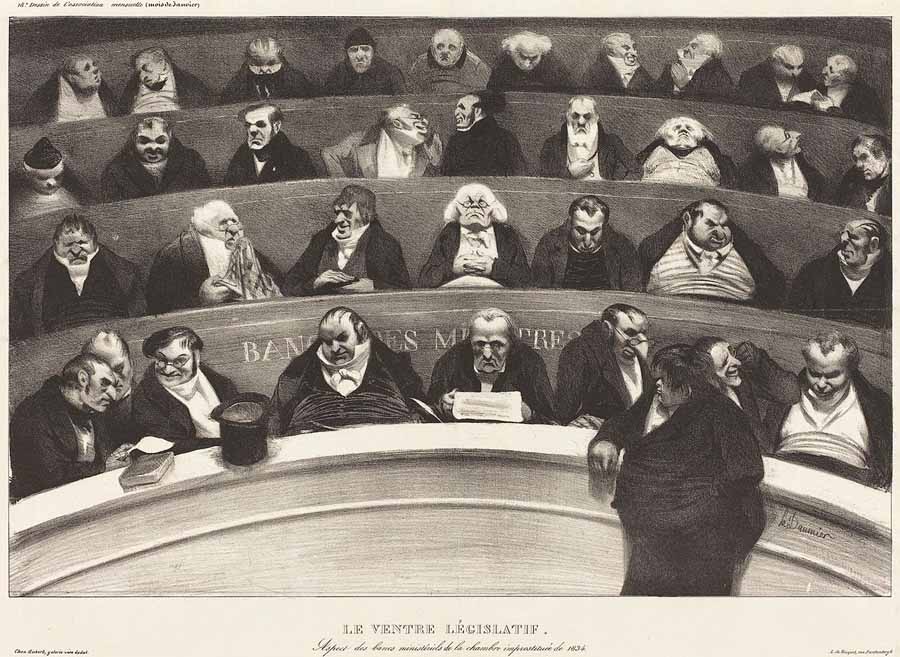

Honoré Daumier, Le ventre législatif, 1834

ABSTRACTS

The Twilight of Monsters. Deformities, Disabilities, and Differences in 19th and 20th Century France

Jean-Jacques Courtine (Auckland University / Queen Mary University of London)

In the second half of the 19th century, Paris was without any doubt a city where you could watch lots of shows and have plenty of fun. But some of the shows that drew crowds to fairground stalls, cafes’ backrooms and boulevards’ theatres would certainly not seem that funny today: this paper will examine the 19th and early 20th century visual culture and entertainment industry, natural sciences and medicine, literature and emotions to understand how the extremely ancient and popular exhibition of abnormal bodies vanished from public places; and why a major shift in the history of the gaze on the human body can be perceived in this disappearance.

Physiognomy Unchained. Caricature as Emotional Intelligence

Paolo Gervasi (Queen Mary University of London)

Physiognomy has been a long-standing and pervading presence in Western Culture. Over time, it has registered the multiple and diverse attempts to connect what is visible of the human body to what is invisible and concerns souls and minds; to establish a relationship between the outside and the inside; to find homologies between superficial lines and deep forces, physical outlines and moral attitudes. In the treatises that belong to the galaxy of physiognomy, the deciphering of the human face is generally enabled by deformation. To grasp the essence of humanness the average human face needs to be confronted with a divergent form. Building on this assumption, this paper will discuss the intimate historical link between physiognomy and caricature: both disclose the true nature of humans by deforming their traits. Caricature creates a permanent tension between physiognomy and pathognomy – i.e., the representation of emotions, and can be described as a “physiognomy unchained”, a particular physiognomic practice in which the psychological comprehension is obtained precisely by forcing the rules and constraints of “official” physiognomy. Caricature activates the instinctual physiognomic consciousness harboured in the human mind, and the equally instinctual capacity of the mind of recognising passions in the alteration of lines.

The Representation of Biological Beauty in the Brain

Tomohiro Ishizu (University College London)

In this talk, I will discuss brain systems for aesthetic judgment in vision, inspired by Francis Bacon’s artworks. I do so especially with reference to the representation of faces and bodies in the visual brain. I will review the evidence which shows that faces and bodies (‘biological’ stimuli) have a privileged status in visual perception, compared to the perception of other stimuli, including man-made products such as houses, chairs, and cars (‘artefactual’ stimuli). I will then show that viewing face and house stimuli that diverge significantly from a normal representation of their forms, which can be found in many of Bacon’s paintings, entails a significant difference in the pattern of brain activation produced, compared to viewing their regular counterparts. I will propose two different concepts, inherited and acquired one, in visual perception and explore what insights into the understanding of the brain they give.

Shape, Posture and Difformity as Social Critique of French Ancien Regime Élites.

Colin Jones (Queen Mary University of London)

For over three decades, the court embroiderer at Versailles, Charles-Germain de Saint-Aubin, kept a secret journal of caricatures which lampooned members of the Parisian and Versailles elites. This paper will explore how he sought to hit his targets through graphic commentary on physical and bodily appearance.

A Kind of Catatonia: Samuel Beckett’s Ghost Trio

Ulrika Maude (University of Bristol)

Samuel Beckett’s second television play, Ghost Trio (1975), stages a seeming disparity between its affectively-challenging subject matter, and the deliberate aestheticism and formalism of its representational strategies. F, the Male Figure – no longer a character – is one of a long line of late-Beckettian ‘players’. Through careful attention to gesture, posture and costume, he assumes a highly-abstracted form – so abstracted, that for whole stretches of the play he resembles one of its many rectangles. This evacuation of subjectivity is reinforced by the fact that F’s face is only encountered in the third and final act of the play. Dehumanization is also at work, rather differently, in the way that F may be said to belong to Beckett’s long line of catatonics. The disparity between the play’s subject matter and its form is made even starker by the austere formal qualities of its medium: the limited, rigidly-framed TV screen, its flatness, the shades of grey in a black and white broadcast, the ‘omnipresent’ televisual light, produced by the firing of a cathode tube onto the television screen, the ‘flat’ or ‘indifferent’ tone of the play’s voice-over and the often ‘staring’ camera eye, as Beckett called it in his manuscript drafts. And yet, the answer to how the play’s affective content is communicated seems to reside precisely in the unusualness and precision of its form, in the clinically-framed shots and the abstracted, calculatedly affectless set, in its detailed foregrounding of the artifice of representation, in its late-modernist, minimal, pared-down style, even in the brevity and semantic reticence of its script. This paper will consider the question of affect and the resistance to affect in Beckett’s television work.

Perfetta deformità: Caricature and Embodiment

Kasia Murawska-Muthesius (Birkbeck College)

Bodily distortion reaches back to ancient art and the medieval marginalia, but it was the theoretical reflection on the seventeenth-century Italian caricatura which valorised deformation as an artistic convention by situating it within the wider framework of the discourse on beauty. Anti-canonical and belligerent, caricature emerged as a novel art form in the Carracci Academy in Bologna, and was practiced by the top Seicento artists, from Guercino and Bernini to Pier Francesco Mola. It was also discussed by major Seicento art scholars, including Giovanni Antonio Massani, writing on Annibale Carracci (1642), the first chronicler of the Bolognese art world Carlo Cesare Malvasia (1678) and Filippo Baldinucci, the biographer of Bernini (1681). This paper will focus on the ways of theorising multiple paradoxes of this subversive art form, which strives for perfetta deformità instead of perfect beauty, which is capable of achieving likeness through deformation, and which serves as a catalyst in bringing communities together by poking fun on the bodily deformities of their members instead of hiding them.

Necessary Deformations. Caricatures and Parodies of Mussolini condottiero in Post-WWII Italy

Beatrice Sica (University College London)

In Fascist Italy, images of Mussolini on horseback could be seen everywhere: in newspapers, magazines, postcards, stamps, artworks, paintings, statues, murals, novels, poems, school textbooks and workbooks. Standing on his horse, Mussolini appeared as the military leader: people would see in him the Roman emperor and the Renaissance condottiero. His images on horseback became so ubiquitous, that reality mixed with fantasy and the real man developed into a myth, an idealized model that embodied the core Fascist values: virility, strength, and military command.

Immediately after the fall of the regime, built images were physically removed; yet the mental image and the myth needed to be deconstructed and challenged differently. Thus, from the mid-1940s to the 1960s, caricatures and parodies of men on horseback were made in Italy that depicted unseated, mutilated, and defeated knights and condottieri. Although most of them were not of Mussolini, it can be argued that these caricatures and parodies function as implicit deformations of the Duce’s figure, which was still vivid in the memory of Italians in those years. In other words, by enacting disguised caricatures and parodies of the icon of Mussolini on horseback that had circulated in Fascist Italy, they offer a disfigurement of the body of the Fascist power.

Charles Meryon’s Crypto-Games

Richard Taws (University College London)

This paper will focus on several prints made by Charles Meryon around the mid-1850s, which might, in various ways, be considered ‘mis-shapen’. Analysis of Meryon’s work has been dominated by the outsize influence of his two primary interpreters, Charles Baudelaire and Walter Benjamin, for whom Meryon’s vertiginous etchings of the capital – constituting, in Benjamin’s words, “the death mask of old Paris” – operated as allegories for the dialectical character of modernity. Here I take a different tack, approaching works Meryon produced in ensuing years, shortly before he was committed to the Charenton asylum, where he died in 1868. My focus is a remarkable pair of relief prints of 1855, identified as proofs for share certificates for a fictional, potentially fraudulent, Franco-Californian company, and, especially, a set of etchings of 1860 titled Le malingre cryptogame. These last prints show a twisted, deformed fungus, identified by Meryon as a cryptogam, a plant which reproduces not by flowers or seeds but by spores, doubled back on itself in an agonizing contortion. Read alongside one another these works allow a different perspective on Meryon’s visual practice, one in which the body and mind in crisis play a central role.

Take a look at the conference’s programme and the speakers’ profiles.