The Museum of London

We visited the Museum of London and saw many fascinating and precious objects from medieval London, such as part of the Eleanor Crosses. The museum is located on the London Wall, close to the Barbican Centre and is a part of the Barbican complex, a collection of buildings created in the 1960s and 1970s as a way of re-developing the bomb damaged area of the City of London. It overlooks the remains of the Roman city wall on the edge of the oldest part of London, now its financial district, and is jointly controlled and funded by the City of London Corporation and the Greater London Authority. The Museum of London is primarily concerned with the social history of London and its inhabitants throughout time and documents this from prehistoric to modern times in several galleries (e.g. London before London (London 450,000 BC to AD 50), Roman London (AD 50-410), Medieval London (410 to 1558), War, Plague and Fire (1550s-1660s) Expanding City: 1666-1850s, People’s City: 1850s-1940s, World City: 1950-today, The City Gallery, The London 2012 Cauldron: (designing a moment).

The museum can be seen as reminiscent of London as a city of layers because it is a result of the continued rebuilding of London. Moreover with regards to archaeological digs, the museum can only dig at sites which are being developed, e.g. in the City of London, Crossrail. This makes the areas in which it carries out activities somewhat random in nature, however this has not dented the work of the museum. Artefacts that are discovered are therefore not always from places which were significant to Londoners, however with this being said, the museum has managed to unearth invaluable information and objects from London’s past.

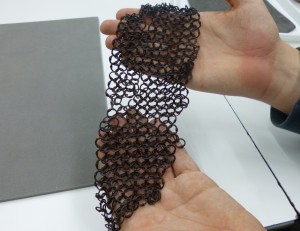

The Museum of London has around 12,000 items dating from the medieval period, and we were fortunate enough to be able hold some of these objects on our trip. The medieval collection is most well-known for containing a large quantity of arms and armour, however this is not necessarily armour of the highest quality, but mostly everyday civilian weapons such as the dagger and chainmail that we were able to hold. Throughout the last thirty years, the museum has acquired additions of small pieces of metalwork from the Thames ‘mudlarks’, another name for its metal detectorists. Some of these discovered artefacts, including brooches and belt fittings help to paint the image of a dweller of medieval London. Another artefact we were able to hold included a floor tile, part of the collection of ceramics and floor tiles, and the majority of these came from Buckinghamshire from around the 1330’s to the 1380’s.

Other famous collections from the Museum of London include the dress and textiles collection, and the Tudor and Stuart Collection. The dress and textiles collection boasts over 24,000 objects, dating from the Tudor era to the modern day, as well as a Henry Matthews Collection of clothing prints dating from the sixteenth century. The Tudor and Stuart Collection contains objects from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and holds over 1500 pieces of cutlery, as well as a collection of edged weaponry manufactured by the Hounslow Sword Factory. There are also dresses, accessories and toys, as well as watches and ceramics that are on display in this collection.

There are a variety of collections available at the Museum of London, but nothing compares with being able to hold medieval artifacts and looking back at their history!

Taverns in terms of prestige were an establishment that was often middling on the social scale, enabling them to cater for the well-off or rich merchants of London. They were vital places for common people to meet, and were often very effective ways to disseminate information to a predominantly illiterate society. They were also ways in which the common people could spread ideas, which often worried the elite and upper classes who were unused to the beginnings of self-awareness shown in cases such as the Great Revolt of 1381.

Taverns in terms of prestige were an establishment that was often middling on the social scale, enabling them to cater for the well-off or rich merchants of London. They were vital places for common people to meet, and were often very effective ways to disseminate information to a predominantly illiterate society. They were also ways in which the common people could spread ideas, which often worried the elite and upper classes who were unused to the beginnings of self-awareness shown in cases such as the Great Revolt of 1381.