As Daniel mentioned, this excursion began where we started on the first day of class. It was a nice callback and set a tone of reflection for this particular outing. In many ways, the Southwark visit served to reinforce some of the themes of the course.

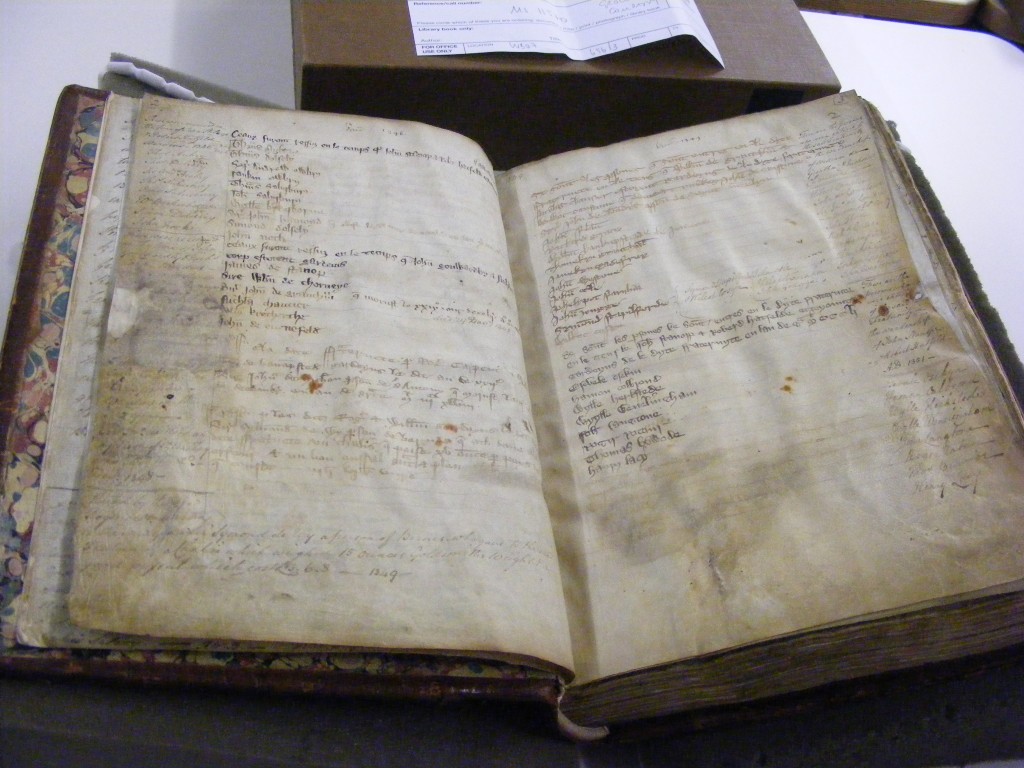

A consistent emphasis was placed on the limits of our archeological evidence. Property, especially in regards to land value, became a connecting theme throughout the course. Much of medieval London no longer exists due to the rebuilding and renovation of valuable properties. However, as we discussed, atmosphere and names are among the last aspects of the urban landscape to change. Southwark’s history as a sanctuary for the marginalized groups of medieval society can still be seen in the contemporary area.

Southwark’s proximity to London made it an attractive prospect, but the land was marshy, making it difficult to build. Land was undeveloped and cheap. This is another note on the importance of property, which in this case served to provide an affordable place for outsiders. Consequently, Southwark attracted immigrants and other alienated groups. Large populations of immigrants and other marginalized groups meant that Southwark existed as a poverty stricken area.

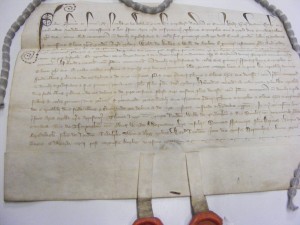

As a poor area, it would be reasonable to expect little information and few sources. This would fit in with the course discussions on the limits of information and the bias inherent in sources. Indeed, far less would be known about this area had there been no interaction with upper classes. As it were, some cross-class interaction did occur. One example is the fact that several houses were owned by various ambassadors to London. Business conditions in Southwark also helped to build contact.

The simultaneous proximity and distance from London created a liminal space that was well suited to the more questionable aspects of society. Things not considered completely moral in public opinion like theater, prostitution, and drinking all found a place in the community of Southwark. The distance afforded such businesses a certain degree of freedom, while still attracting patrons from London proper. Brothels showcase this unique relationship particularly well. Church teaching dictated that extramarital activities were wrong and should be punished. As such, bordellos were condemned in the City of London. Of course, demand still existed and prostitution flourished on the opposite bank. Interestingly, the Bishop of Winchester owned several brothels, despite his association with the church. This was made possible by the social distinction between the two spaces.

However, such spatial division served to further disadvantage the marginalized residents of Southwark. Inclusive spaces were reserved for those of upper classes with better reputations. Exclusion prevented access to the social capital necessary for forming valuable networks. This built up a culture of poverty wherein poorer people could not make the connections necessary for escaping their financial situation.

Overall this excursion, and the course as a whole, provided tools for looking at medieval culture through a much broader historical lens. The themes mentioned above built a sense of course coherence that enabled greater exploration of medieval life in London.