In the twelfth century the Bishop of Winchester was one of the most important men in the country. Traditionally the town of Winchester had been the site of the royal treasury, and the Bishop was usually entrusted with the job of royal treasurer. As such, he would have held considerable power and influence within the country. He would also have needed to visit the King and attend him at court frequently, which meant he required a residence in London which was fit for his station. This need precipitated the building of the Bishop of Winchester’s Palace in Southwark.

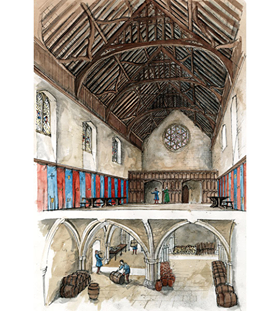

Dated to 1136, the building was originally a lavish complex centred around two courtyards. The Palace also had gardens, a tennis court and bowling alley, a prison, a brewery, a butchery and direct access to the river from the large cellar under the Great Hall. What remains standing today is little more than one wall of the originally impressive Great Hall. The most striking feature of the ruin we have left today is the large rose window near the top of the wall. This was most likely not included in the original construction of the building, but was instead added in the fourteenth century during the expansion of the Hall carried out by the Bishop William of Wykeham.

The Palace was frequently used by the Bishop for many centuries, and was one of many similar residences in London that were the private homes of important churchmen. Lambeth Palace, for example, served as the London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury. However, with the diminishment of the Bishops of Winchester’s importance in the seventeenth century, the Palace was no longer maintained for his sole use and was divided into tenements. The building was then mostly destroyed by fire in 1814, and further damage was dealt by bombing during World War Two. What little can be seen of the Palace today was uncovered during the course of redevelopment of the site in the twentieth century.

The Bishop of Winchester’s Palace was not actually in the City of London itself in the medieval period. At that point what was considered the City – and the area subject to its jurisdiction – was only the land that was actually within the walls of London. Therefore the Palace was in fact outside the city, and was in Surrey, which was the largest manor owned by the diocese of Winchester. This separation from the City, and more importantly its jurisdiction, allowed activities such as gambling and businesses like brothels and theatres to operate unhindered in Southwark, where in the City they would be illegal or heavily regulated. The Bishop of Winchester in fact took part in overseeing some of this trade, taking rent from brothels and generally ensuring things didn’t get too out of hand. The area became known as the Clink Liberty, the name coming from the notorious Clink prison which was in the same area. This also led to the expression ‘to be in the clink’, or in prison, which is still in use to this day.

By Morghan Williams and Libby Keir

References:

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1002054

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol22/pp45-56#s2