The Museum of London is located in the Barbican, an area that had been rebuilt throughout the 1960s after substantive war damage during World War Two. We were lucky enough to have a curator exclusive to our group who was able to explain the layout of the museum and the reasoning of why it was laid out in this specific way. Although we concentrated on the medieval galleries the museum holds artefacts from the Roman era all the way to present day. The common theme that runs through the gallery is the River Thames and this was evident on the glass panels that had river symbols on it and names of fish that were resident of the Thames.

As this museum is a purpose built building rather than a converted stately home the designers had much more scope to design the museum to best display its artefacts and this is evident in the way the objects are displayed with its special low lighting that preserves the artefacts.

The objects on display varied enormously from decorated pieces of masonry to gaming artefacts such as counters and dice as well as items of clothing such as shoes.

We had the opportunity to have a good look around the medieval gallery and there was a particularly interesting exhibition where in an alcove there was a projection of the records of the names of people on a rolling screen of who had died during the Black death along with their occupation.

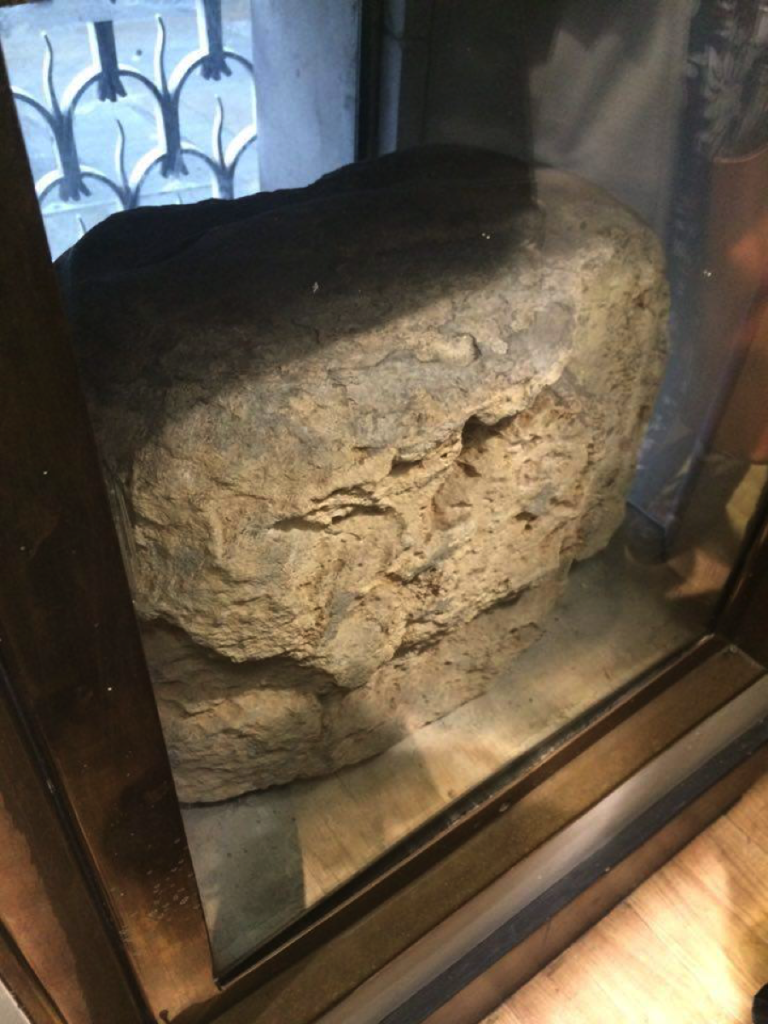

Perhaps the most revealing part of the excursion was the object handling. We had the privilege of handling many objects from the medieval era that have been found in London, many found in the river Thames or on sights of historical significance. Looking at many different objects from coins to horse shoes the object that we feel best sums up daily life in London that also allowed us to draw parallels to modern London was the money box. This particular moneybox (see picture) was in remarkable condition and was made from Surrey white ware, which was a cheap and common material in the period. The box itself was generally glazed with a green glaze, known as Tudor green.

Many of these money boxes were found in their place of origin, in and around Surrey, but many were found at places of commerce and trade such as the Globe Theatre. The money box animates medieval London life and highlights how much the London economy was so intertwined with aspects of leisure and everyday life. This can easily be associated with modern London and shows how trade and commerce have always played an important role in the life of Londoners. The money box can be compared to the card machine or the modern bank, an invention that allows people to pay for items, a service or an experience or save money safely by minimising the human interception in the transaction. Like many other exhibits and objects on display at the Museum of London, the money box enables us to relate to the everyday lives of Londoners in the medieval period.