While very few medieval London buildings exist today, much of the layout and streets still remain along with rebuilt churches. On the afternoon of June 13th 1381, the rebels from Southwark and Kent gathered at the south end of the London Bridge, the only passage into London at the time. The old bridge was slightly east of the modern day bridge and aligned with the St Magnus church, which still stands today. People that came into London would have walked by the church upon crossing the bridge. As we saw in St Magnus, the old bridge also contained many shops and the St Thomas Becket chapel. The many religious buildings demonstrated the power of the church at the time, explaining the rebels’ decision to execute several archbishops later on. After threatening and forcing the keepers to lower the bridge, they crossed into London and began heading toward the Savoy Palace.

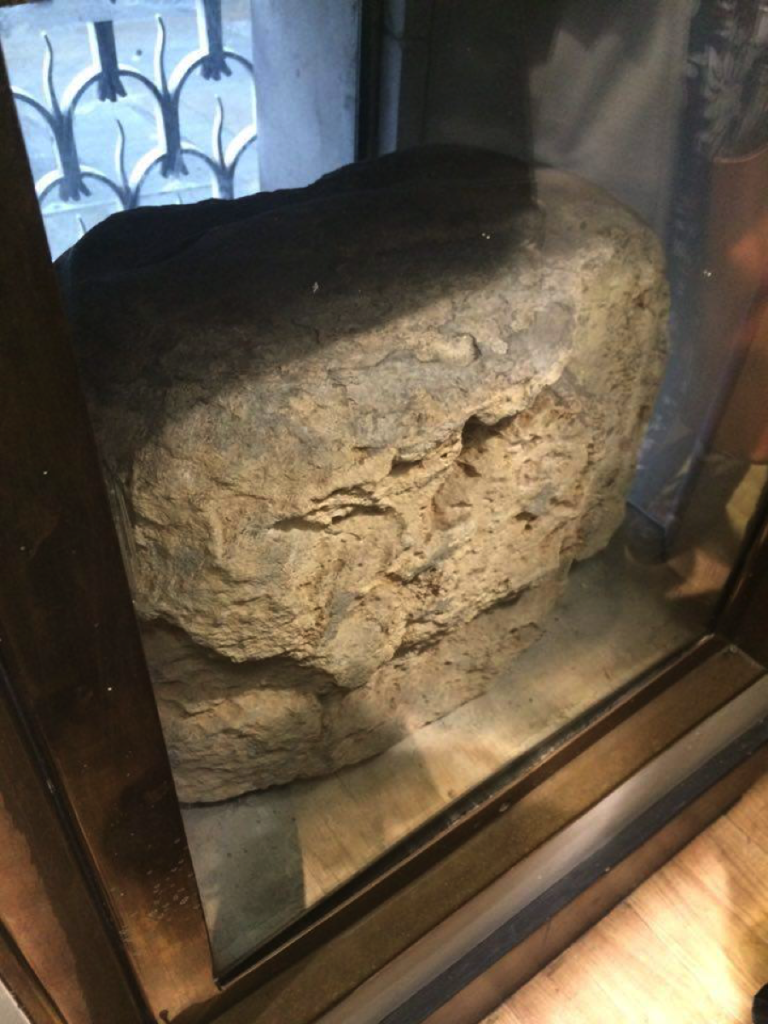

After crossing the London Bridge and visiting St Magnus Church, we began to make our way northwest toward St Mary-le-bow Church. The first landmark we came upon was the Monument to the Great Fire of London itself, which was built in the same spot where St. Margarets Fish Street Hill had been located as that was the first church to burn down during the fire. From the Monument we continued on our path and took a quick stop at a local WH Smith shop. Surprisingly, this little store holds one of the oldest pieces of surviving London history: the London Stone. No one is entirely sure what the stone was originally used for, but it has been around for almost 1000 years and is one of London’s great treasures and mysteries.

After crossing the London Bridge and visiting St Magnus Church, we began to make our way northwest toward St Mary-le-bow Church. The first landmark we came upon was the Monument to the Great Fire of London itself, which was built in the same spot where St. Margarets Fish Street Hill had been located as that was the first church to burn down during the fire. From the Monument we continued on our path and took a quick stop at a local WH Smith shop. Surprisingly, this little store holds one of the oldest pieces of surviving London history: the London Stone. No one is entirely sure what the stone was originally used for, but it has been around for almost 1000 years and is one of London’s great treasures and mysteries.

Carrying on our journey, we headed towards St Paul’s Cathedral, stopping to see an old narrow medieval street, now a shopping alley, as an example of the historical surroundings the peasants would have travelled through.

Due to adverse weather conditions we were unable to visit the Tower of London on this day, but when faced with the Tower itself, it is easy to imagine the intimidating icon it once was in medieval London. Once we reached the Cathedral, we considered how information was shared during the time of the revolt; there were no nationalised newspapers or magazines; information was spread through word of mouth. Though this seems like a rather slow form of communication from a modern perspective, the extent of the Revolt of 1381 is proof as to its effectiveness during this period.

Our final destination was the location of the original Savoy Palace. After walking along the Strand, which was historically a very desirable location for nobility and currently remains a site of luxury hotels and notable buildings, we came across the Savoy Hotel. An impressive display of gold, mirrors, and historical plaques lined the entranceway to the Hotel. During the 1381 revolt, the Palace was destroyed by the rebels; years later, the Savoy Hospital took its place, and after that was burned down, the Savoy Hotel was built many years later. The Savoy Chapel exists right next to the Savoy Hotel; unfortunately, the gate to the Savoy chapel was closed, so we were not able to venture in.