This week we were engaging with archaeological and document evidence to discover more about the Death and its impact on London. The first stop on our tour was the Royal Mint. Unfortunately, the site was closed to us last minute as there has always been a difficult relationship between the present day mint and the archaeological site beneath. Beneath the Royal Mint is the site of St. Mary Graces a Cistercian abbey built in 1350. After the arrival of plague in London in 1348 the cemetery was expanded to cater for the extra dead. In 1980s the Royal mint was rebuilt and excavated, revealing three mass trenches with 762 graves and 213 coffins. Much of the writing and documentary evidence about the Black Death suggests there was a complete breakdown of society. However, the neat graves of the plague pits and St. Mary Graces suggest a high level of planning and order.

about the Death and its impact on London. The first stop on our tour was the Royal Mint. Unfortunately, the site was closed to us last minute as there has always been a difficult relationship between the present day mint and the archaeological site beneath. Beneath the Royal Mint is the site of St. Mary Graces a Cistercian abbey built in 1350. After the arrival of plague in London in 1348 the cemetery was expanded to cater for the extra dead. In 1980s the Royal mint was rebuilt and excavated, revealing three mass trenches with 762 graves and 213 coffins. Much of the writing and documentary evidence about the Black Death suggests there was a complete breakdown of society. However, the neat graves of the plague pits and St. Mary Graces suggest a high level of planning and order.

Next, we passed through Jewry Street and briefly stopped off at the Holy Trinity Priory. The name Jewry Street reflects the medieval reality. We know Jews lived here because excavations have exposed artefacts used in Jewish rituals. However, since the expulsion of the Jews in 1290 no Jews have lived here for 700 years. Streets like this show us how little the layout and street names change in London.

Next, we passed through Jewry Street and briefly stopped off at the Holy Trinity Priory. The name Jewry Street reflects the medieval reality. We know Jews lived here because excavations have exposed artefacts used in Jewish rituals. However, since the expulsion of the Jews in 1290 no Jews have lived here for 700 years. Streets like this show us how little the layout and street names change in London.

Holy trinity priory was one of the most influential monasteries in London. Established by  Queen Matilda around 1108. As a result of the Black Death there was a decline in donations and like many of the other monasteries in London the Holy trinity Priory went bankrupt in 1532 before the Dissolution of the monasteries in 1536. A part of the building still survives today and this shows us that the only medieval buildings that survive today are those whose owners have considerable wealth and power: buildings connected either to the monarchy, guilds or the church.

Queen Matilda around 1108. As a result of the Black Death there was a decline in donations and like many of the other monasteries in London the Holy trinity Priory went bankrupt in 1532 before the Dissolution of the monasteries in 1536. A part of the building still survives today and this shows us that the only medieval buildings that survive today are those whose owners have considerable wealth and power: buildings connected either to the monarchy, guilds or the church.

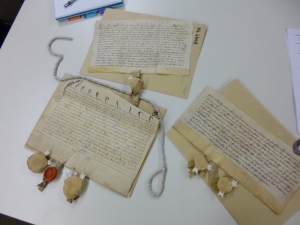

Our last stop was Guildhall, with our particular interest being the archives kept there. A lot  of the evidence we have for the Black Death comes from original documents, such as those kept at the Guildhall archives. These documents gave us information beyond that of the text itself. Though, at best, we had rudimentary Latin and the script was difficult to read we were still able to appreciate the document itself due to the condition the manuscripts had been kept in. Many still had their original attachments such as seals which were used to authenticate documents. The first document we examined closely was a deed for the exchange of property between recently widowed mother and daughter during the Black Death. It showed that there were changes in society that necessitated the need to take more care of each other but it also demonstrates that there was not a breakdown in society. Like the trenches of the plague pits, the documents reflect that things are not being done randomly but with planning and in an orderly fashion. The document is part of a series of manuscripts for the same family both during and after the advent of the plague. The seals attached to the documents belong to the company of Weavers and therefore reflects the responsibility of guilds to look after their own.

of the evidence we have for the Black Death comes from original documents, such as those kept at the Guildhall archives. These documents gave us information beyond that of the text itself. Though, at best, we had rudimentary Latin and the script was difficult to read we were still able to appreciate the document itself due to the condition the manuscripts had been kept in. Many still had their original attachments such as seals which were used to authenticate documents. The first document we examined closely was a deed for the exchange of property between recently widowed mother and daughter during the Black Death. It showed that there were changes in society that necessitated the need to take more care of each other but it also demonstrates that there was not a breakdown in society. Like the trenches of the plague pits, the documents reflect that things are not being done randomly but with planning and in an orderly fashion. The document is part of a series of manuscripts for the same family both during and after the advent of the plague. The seals attached to the documents belong to the company of Weavers and therefore reflects the responsibility of guilds to look after their own.

Guildhall was built between 1411 and 1440 and survived both the Great Fire of London and  the Blitz, making it is the only secular stone structure dating from before 1666 left still standing in the City. The word ‘guildhall’ is said to derive from the Anglo-Saxon ‘gild’ meaning payment, so it was probably where citizens paid their taxes but it was also where the ruling merchant class held court, fine-tuned the laws and trading regulations that helped create London’s wealth. During the Tudor period it was the setting for famous trials, including those of Anne Askew, Sir Nicholas Throckmorton, Lady Jane Grey, and Thomas Cranmer. The main role of the guilds was to protect the quality and reputation of a trade and the members of a company, but they also played a role in parish business and religious observance. The power, both economic and political, wielded by the medieval guilds was immense. By the early 14th century, no-one could practice a trade, set up shop, take apprentices or vote unless they were admitted to a livery company.

the Blitz, making it is the only secular stone structure dating from before 1666 left still standing in the City. The word ‘guildhall’ is said to derive from the Anglo-Saxon ‘gild’ meaning payment, so it was probably where citizens paid their taxes but it was also where the ruling merchant class held court, fine-tuned the laws and trading regulations that helped create London’s wealth. During the Tudor period it was the setting for famous trials, including those of Anne Askew, Sir Nicholas Throckmorton, Lady Jane Grey, and Thomas Cranmer. The main role of the guilds was to protect the quality and reputation of a trade and the members of a company, but they also played a role in parish business and religious observance. The power, both economic and political, wielded by the medieval guilds was immense. By the early 14th century, no-one could practice a trade, set up shop, take apprentices or vote unless they were admitted to a livery company.