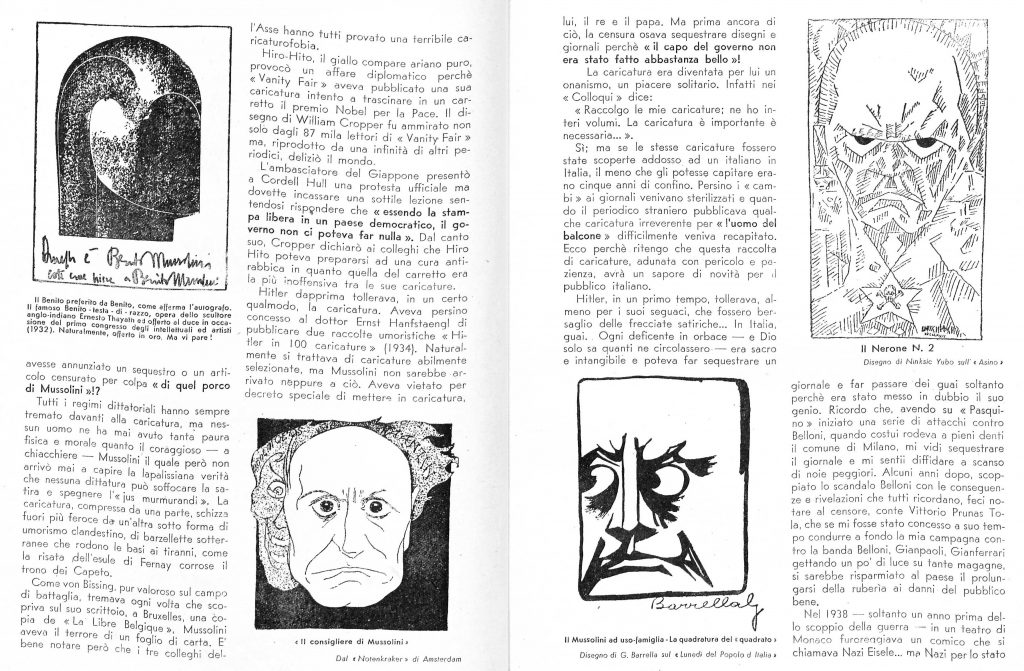

Here’s the amazing poster of the Mis-Shapings conference. And the booklet with the full programme and presentation. Thanks to Livia for both!

Monthly Archives: July 2018

Mis-Shapings

On Thursday 13th September 2018 will take place at Queen Mary University of London (Mile End Campus, Arts One Building, Room 128) the international conference Mis-Shapings. The Art of Deformation and the History of Emotions. I’m organising the conference, as coordinator of the Marie Skłodowska-Curie research project Misshaping by Words, in association with the Queen Mary Centre for the History of Emotions.

Concept

A well established and long-standing bond exists between the representation of the forms and postures of the human figure and the expression of emotions. But how does this change when the body represented is deformed or mis-shapen? This is a question that an interdisciplinary range of scholars, covering a wide chronological period that extends from the Renaissance to the 20th century, will explore in the one-day Mis-Shapings conference.

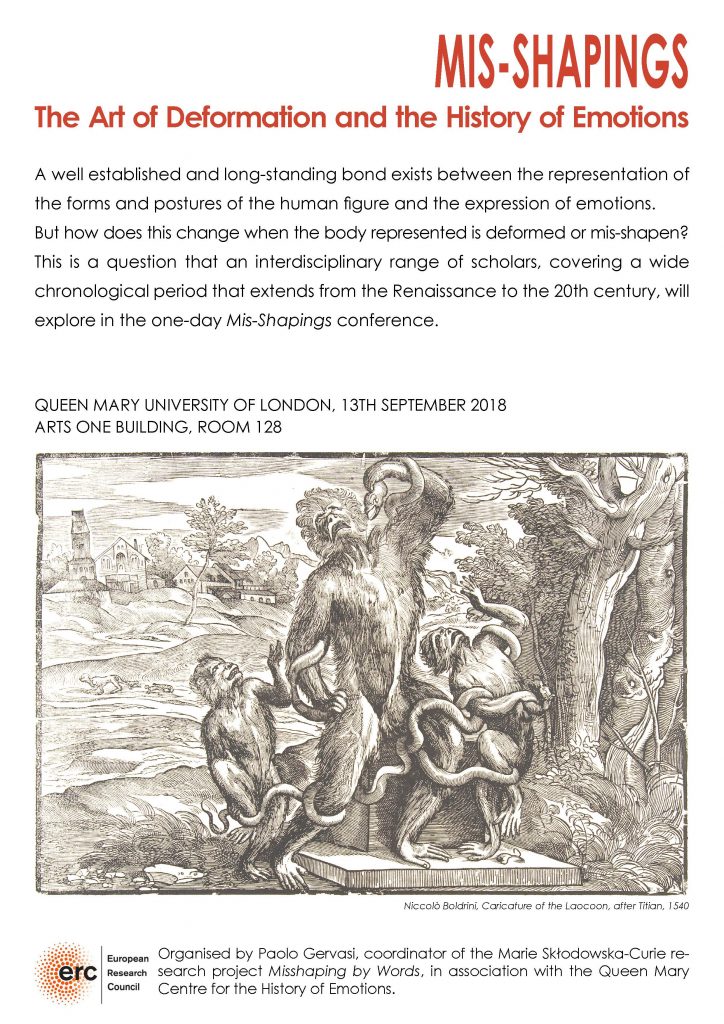

Niccolò Boldrini, Caricature of the Laocoon, after Titian, 1540

Mis-Shapings: abstracts

Here are brief descriptions of the papers that will be presented next September 13th at the Mis-Shapings conference.

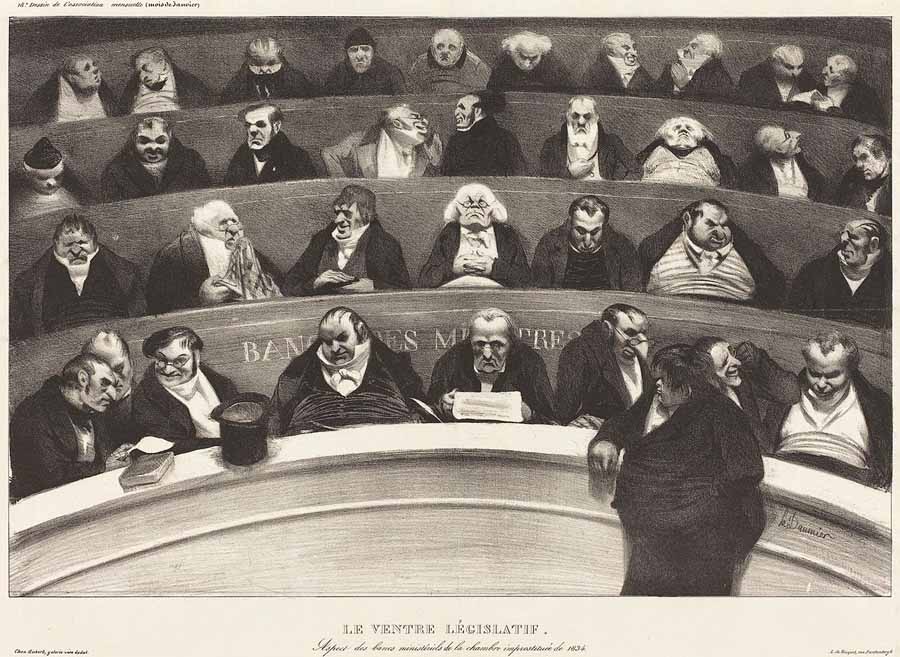

Honoré Daumier, Le ventre législatif, 1834

Mis-Shapings: speakers

Here are the bio-bibliographical profiles of the Mis-Shapings conference‘s speakers.

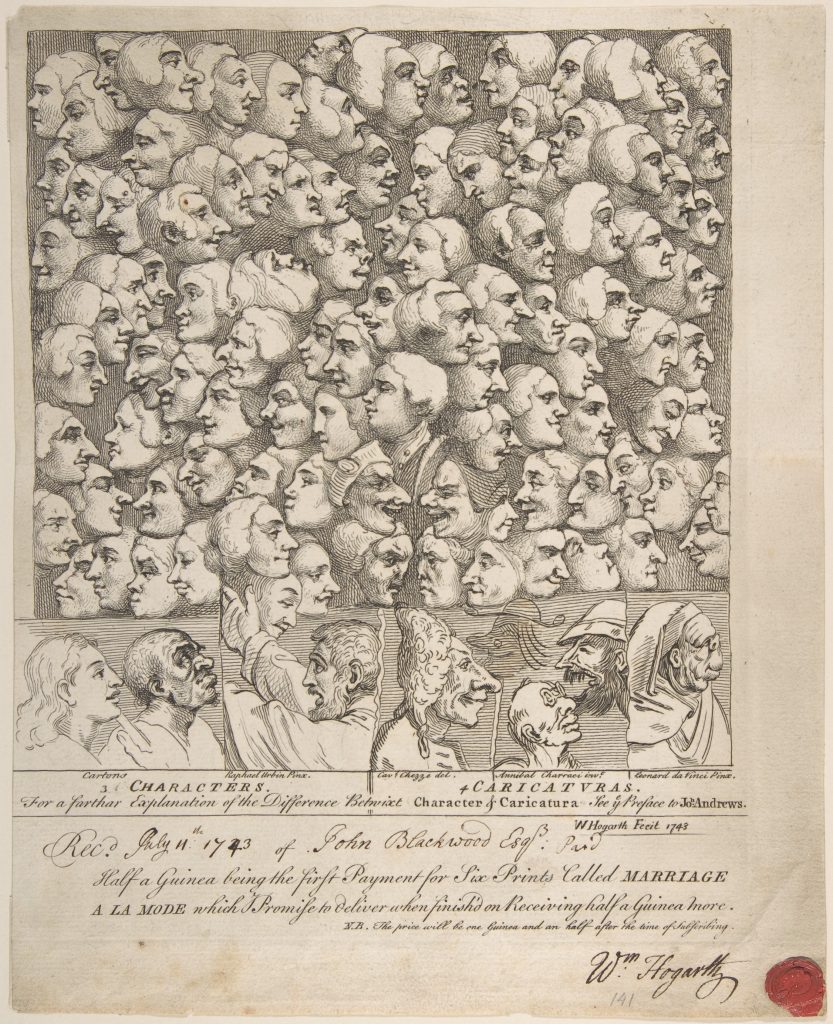

William Hogarth, Characters and Caricaturas, 1743

Socialising anger. Fascism and emotions

Last June 22nd I participated in the Literature and Social Emotions Conference at the University of Bristol. I presented a paper titled Socialising Anger. Literary Representations of Emotional Communities under Fascism, which is a development of the research I first presented one year ago and will result in a broader scrutiny on the representation of emotions in fascism-related Italian literature. What follows is the text of the Bristol’s paper.

1.

Italian fascism pursued strict management of public feelings. It aimed at a wide and deep control of human thoughts and experiences. That is to say, it built what William Reddy defines an ‘emotional regime’; it established a set of practices which inculcated normative emotions, like enthusiasm, exaggerated optimism, national pride. Nevertheless, the euphoric feelings displayed in public represent just one of the emotional layers of fascist Italy. Despite the appearance of unanimous acceptance, fascism largely derived consensus from violence and intimidation. As denounced by Carlo Emilio Gadda in the very first lines of his anti-fascist satire Eros e Priapo, written in 1944-1945.

Collective and individual consciousness, threatened by the knife, the truncheon, the torture; and silenced by prisons, extorsions, vetos against free expression; it was concealed in a hidden, invisible lagoon of history, beyond hate and dullness, and belonged to the refugees, the persecuted, the prisoners, the humiliated, children of deportees and executed to death.

Along with material and physical coercion, fascism caused the emotional suffering of part of the population. Gadda sketches the existence of what Reddy would call an ‘emotional refuge’, a cluster of social conditions and related practices diverging from the emotional regime.