The third issue of the journal L’Età del Ferro has just been released. In it I published the following text, responding to the harsh criticisms opposed to the assumption of neurocognitive perspectives in the study of literature, and more in general to the most recent development in the field of humanities, contained in the journal’s previous issue. The complete title of my intervention sounds Doctor Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Humanities.

Category Archives: 18th Century

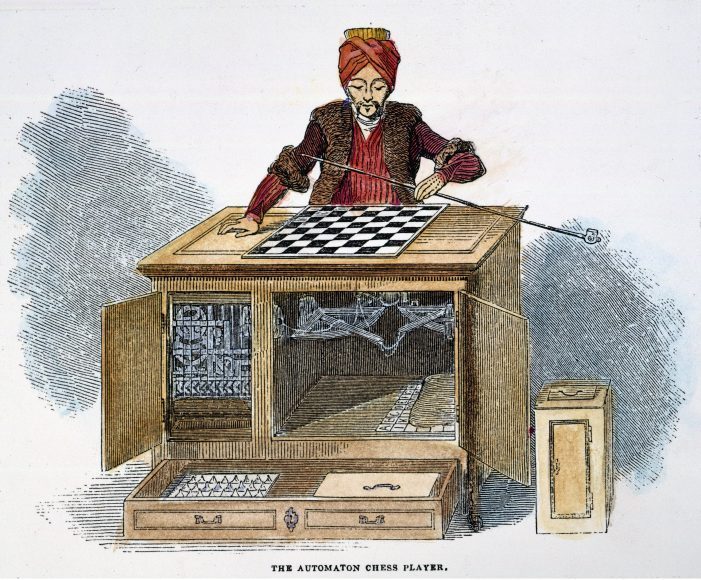

Clockwork Mind

What follows is the text of the article I published within the magazine Oracoli. Saperi e pregiudizi al tempo dell’Intelligenza Artificiale. The Italian title was La mente nell’ingranaggio.

Non è il primo automa della storia, non è nemmeno davvero un automa, ma è uno dei congegni più suggestivi dell’era moderna, sicuramente il primo a porre il problema della concatenazione e dell’ibridazione tra essere umano e macchina. Per questo il Turco giocatore di scacchi, concepito nel 1769 dal barone ungherese Wolfgang von Kempelen per meravigliare l’imperatrice Maria Teresa d’Austria e la sua corte, resta una delle invenzioni più famose di sempre, un “robot” ante-litteram che non si lascia archiviare come una bizzarra curiosità antiquaria, ma torna a interrogare l’umanità, quasi come se tra i suoi ingranaggi fosse nascosto il mistero originario della tecnologia.

Oracles

I participated in the organisation of the project Oracoli. Saperi e pregiudizi al tempo dell’Intelligenza Artificiale, designed by the publisher Luca Sossella Editore with Emilia Romagna Teatro Fondazione and Unipol Gruppo. It is a series of lectures on the philosophical, historical, social, ethical and economic challenges connected to the emergence of artificial intelligence. I designed and edited a journal describing the project and expanding the reflection around the main issues it will address.

I also published an article in the online magazine CheFare, Oracoli’s partner, discussing how literature over time diversely imagined possible extensions, evolutions, empowerments and re-creations of the human mind and body. Continue reading

Caricature as emotional knowledge

I publish here the talk I’ve given at the Mis-Shapings conference last September 13 at Queen Mary University.

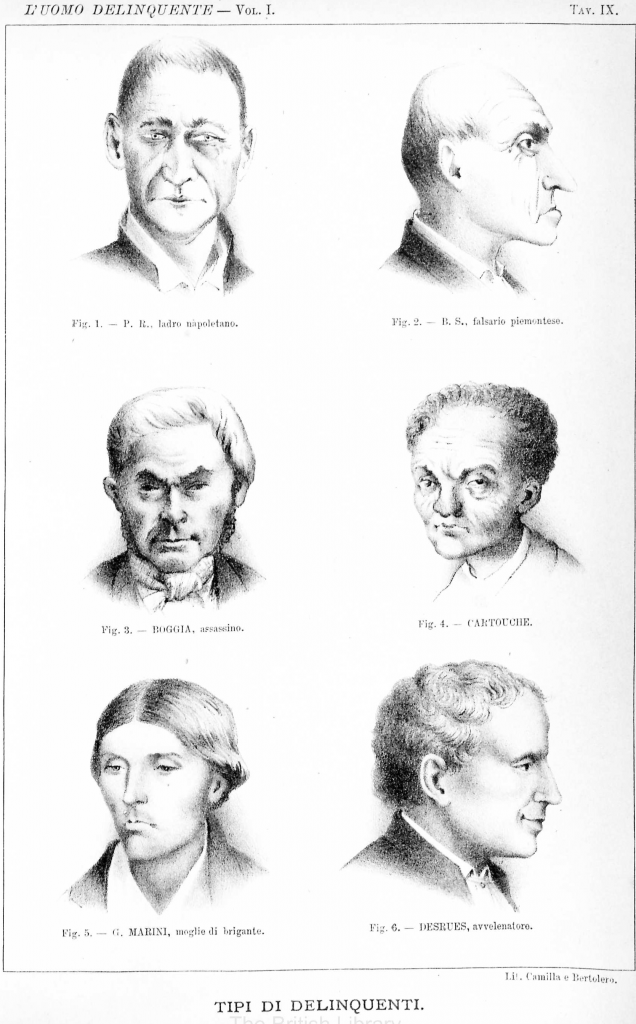

Do we believe in physiognomy? Do we believe, as the Italian anthropologist Cesare Lombroso did, that psychological, emotional, moral attitudes of the individuals can be divined by observing the shape and features of the face?

No, of course we don’t. Physiognomy is pseudo-science, dismissed knowledge, superstition. We can’t make assumptions merely relying on appearances. Can we?

Actually, we do. We do it in our daily life, often unintentionally. But even when we look at artworks we allow us to believe in physiognomy. Continue reading

Mis-Shapings

On Thursday 13th September 2018 will take place at Queen Mary University of London (Mile End Campus, Arts One Building, Room 128) the international conference Mis-Shapings. The Art of Deformation and the History of Emotions. I’m organising the conference, as coordinator of the Marie Skłodowska-Curie research project Misshaping by Words, in association with the Queen Mary Centre for the History of Emotions.

Concept

A well established and long-standing bond exists between the representation of the forms and postures of the human figure and the expression of emotions. But how does this change when the body represented is deformed or mis-shapen? This is a question that an interdisciplinary range of scholars, covering a wide chronological period that extends from the Renaissance to the 20th century, will explore in the one-day Mis-Shapings conference.

Niccolò Boldrini, Caricature of the Laocoon, after Titian, 1540

Mis-Shapings: abstracts

Here are brief descriptions of the papers that will be presented next September 13th at the Mis-Shapings conference.

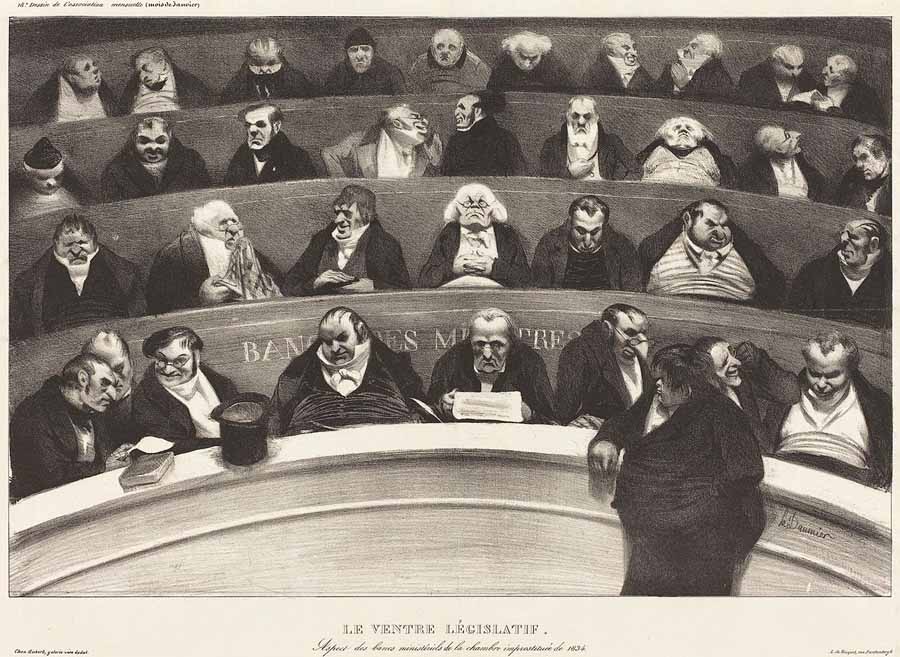

Honoré Daumier, Le ventre législatif, 1834

Mis-Shapings: speakers

Here are the bio-bibliographical profiles of the Mis-Shapings conference‘s speakers.

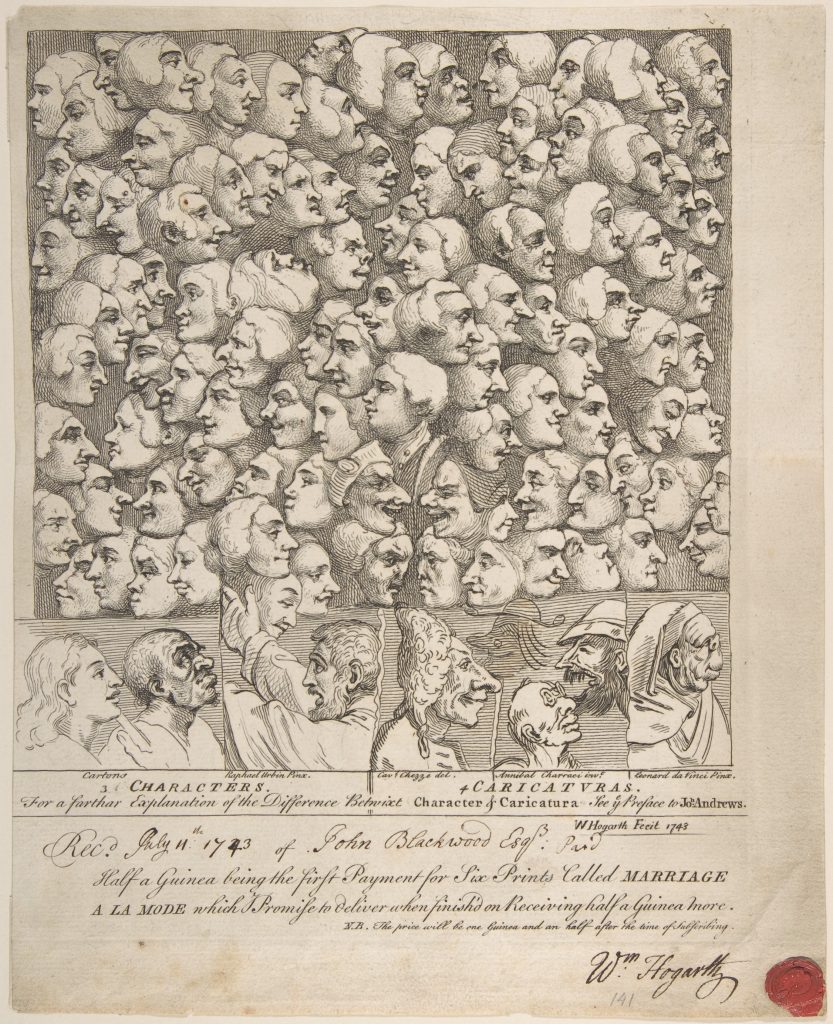

William Hogarth, Characters and Caricaturas, 1743

Parini: last days of aristocracy

In 1763 the Abbot Giuseppe Parini composes the poem Il Giorno, a satirical text addressing the inactive, lazy, superficial life of the aristocracy. Pretending to be an ode written in praise and for the education of a Young Gentleman, the poem harshly criticises the parasitic emptiness of noblemen and women. As a parody of a eulogy, Il Giorno deforms the classical poetic style, applying the language and rhetoric of epic and mythological tradition to the frivolous daily activities of the gentleman. The text provides a series of caricatures: first, the Young Lord is scared to death by the word “work”, and his hair stands on end (vv. 54-56):

Ma che? Tu inorridisci, e mostri in capo,

qual istrice pungente, irti i capegli

al suon di mie parole?